The Chief Secretary’s Papers, 1770-1830

Delving Deeper

Step inside the hidden corridors of power at Dublin Castle, where the Irish Chief Secretary’s Office once shaped Ireland’s destiny. Delve into the history of the central administrative force in Dublin Castle from the 18th century onward. Uncover its central role in shaping policy, managing parliamentary affairs, and orchestrating state security. With detailed archival context and historical background, this page will guide researchers through the rich legacy of Ireland’s Chief Secretaries.

Cite This Essay: Timothy Murtagh, ‘The Chief Secretary’s Papers, 1770–1830 — Delving Deeper’ (VRTI 2025).

Historical Background

Since the Norman conquest of the twelfth century, a chief governor had always been appointed to govern Ireland on England’s (and later Britain’s) behalf. Initially called the Justiciar, the title later changed to Lord Deputy, and by the eighteenth century, the role was known as that of Lord Lieutenant or Viceroy. During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, this chief governor was always assisted by a primary or ‘chief’ secretary, who acted as their main aide in organizing and implementing policy. By the eighteenth century, the Chief Secretary’s role had expanded significantly, supported by a growing bureaucracy (the Chief Secretary’s Office) that emerged as the central coordinating agency within the various offices in Dublin Castle.

The Chief Secretary was the Lord Lieutenant’s nominee, arriving in Ireland at the beginning of the Lord Lieutenant’s tenure and usually departing when a new Lord Lieutenant was appointed. However, during his time in office, the Chief Secretary served at the Lord Lieutenant’s pleasure as the head of his secretariat. Crucially, it was during the eighteenth century that the various offices previously associated with the Lord Lieutenant gradually coalesced into a single central organization.

The Chief Secretary’s Office served as the primary channel for implementing the Lord Lieutenant’s directives, carrying out many of the functions that, in England, were typically managed by the Home Office. The Chief Secretary oversaw the payment of the military and civil establishments in Ireland and was the principal link between government departments in England and their Irish counterparts. In addition, the Chief Secretary’s Office played a key role in administering justice in Ireland. It supervised local magistrates, corresponded with justices of the peace, received memorials from prisoners and convicts, and transmitted the Attorney General’s orders to the relevant authorities. In some instances, the Chief Secretary’s Office exercised direct control in judicial matters. The Lord Lieutenant had the power of pardon, sometimes intervening to mitigate harsh sentences. Following the Irish Convention Act of 1793 (reinforced by later insurrection acts), the Lord Lieutenant could also assume direct jurisdiction over disturbed regions of the country.

The Chief Secretary was also a member of the Irish House of Commons and was regarded as the principal representative of the administration’s policy. The Lord Lieutenant, receiving instructions from the British cabinet, was tasked with ensuring the passage of key legislation, particularly money bills, through the Irish Parliament. A crucial responsibility of the Chief Secretary, therefore, was parliamentary management. However, in the first half of the eighteenth century, this task was complicated by the convention that the Lord Lieutenant resided in Ireland only when its Parliament was in session—roughly eight months every two years. In the Lord Lieutenant’s absence, three Lords Justice managed routine administrative affairs. This arrangement meant that the Viceroy rarely had the opportunity to build personal political networks in Ireland. English Lord Lieutenants often had little knowledge of Irish politics, being largely unfamiliar with the intricate web of competing political families and interests. As a result, many appointees found the position unappealing and had little inclination to immerse themselves in Irish affairs. Instead, they subcontracted the management of Parliament to an elite group of Irish MPs known as the ‘undertakers,’ who undertook to advance the Crown’s legislative business. In exchange, these undertakers were granted considerable government patronage, distributing offices and pensions among their supporters. As several historians have noted, the period from 1730 to 1770 was essentially ‘the age of the undertakers.’

However, a series of political crises after 1750 prompted the British government to reassess its governance of Ireland. When George Townshend became Lord Lieutenant in 1767, he was determined to end reliance on the undertakers and establish direct government from Dublin Castle. His Chief Secretary, Sir George Macartney, played a key role in this process, assuming direct management of the Irish Parliament and negotiating directly with MPs to secure the passage of government-sponsored legislation. Macartney also strengthened the Castle’s control over revenue and treasury affairs and successfully expanded the Irish establishment’s military capacity. His proactive approach led to his recognition as the first ‘real’ Chief Secretary, marking the office’s emergence as a ministerial role that would define it thereafter.

The period following Macartney’s tenure, particularly the 1770s, was marked by significant imperial strain. As tensions in America escalated, the British government sought to rationalize its Irish administration as part of a broader strategy to stabilize the empire. In Ireland, this coincided with efforts by local reformers, led by Henry Grattan, to advocate for greater parliamentary autonomy. In 1782, the Irish Parliament secured the right to legislate independently of Westminster, ushering in the era known as ‘Grattan’s Parliament.’ With British control over the Dublin legislature weakened, successive administrations had to develop policies that relied on securing a parliamentary majority through strategic patronage. However, MPs from open constituencies increasingly resisted being seen as mere clients of Dublin Castle, as they needed to at least appear responsive to their local electorates.

Throughout this period, the Chief Secretary’s Office played a crucial role in managing Ireland’s more autonomous legislature while simultaneously ensuring state security amid growing unrest. Heated debates over Irish Catholic Relief in 1792–93 revealed deep divisions between London ministers and Dublin politicians. The controversial decision to extend the franchise to Irish Catholics was achieved largely through the efforts of Chief Secretary Robert Hobart, despite fierce opposition from Ascendancy figures and even his own Lord Lieutenant. The remainder of the 1790s saw the administration struggle to balance governance with the rising threat of rebellion, culminating in the 1798 uprising. In its aftermath, the final adjustment to the Anglo-Irish constitutional relationship came with the Act of Union, orchestrated by Chief Secretary Lord Castlereagh and his staff.

The Act of Union of 1801 was a transformative moment, formally merging Ireland with Great Britain to create the United Kingdom. However, the practical implementation of the Union was fraught with challenges. British ministers oscillated between policies that emphasized Ireland’s distinctiveness and those aimed at fully integrating it into the British system. The Chief Secretary’s Office became a focal point for these debates. Some officials viewed the Union as an opportunity to dismantle Ireland’s separate executive structures, while others believed that the Lord Lieutenant and Chief Secretary should retain significant autonomy in Dublin. In 1801, Home Secretary Thomas Pelham briefly attempted to subordinate the Lord Lieutenant and Chief Secretary to the Home Office, but this was successfully resisted by Lord Lieutenant Hardwicke. The Chief Secretary’s Office thus continued to oversee Ireland’s extensive administrative state.

After the Union, the Chief Secretary’s importance grew relative to the Lord Lieutenant. He assumed a more prominent role in managing Irish parliamentary affairs in London, spending recesses in Ireland but attending Westminster during sessions to defend Irish policy. As the primary liaison on Irish affairs for the British cabinet, the Chief Secretary became the key conduit between the Prime Minister and the Lord Lieutenant. However, the full extent of the office’s power was not immediately apparent. Between 1801 and 1812, ten different Chief Secretaries held the position, creating instability. It was not until the arrival of Sir Robert Peel in 1812 that the office’s influence was fully realized.

Peel, who served as Chief Secretary until 1818, played a pivotal role in Irish governance, particularly in law enforcement. Recognizing that military force alone could not maintain order, he established the Peace Preservation Force (PPF) in 1814, a centrally controlled paramilitary police unit that later evolved into the Irish Constabulary. Peel was assisted by Under-Secretary William Gregory, who managed much of the government’s business from 1812 to 1830. Gregory’s tenure was marked by an uncompromising commitment to law and order and staunch opposition to Catholic rights, ultimately leading to his dismissal in 1830 after Catholic Emancipation.

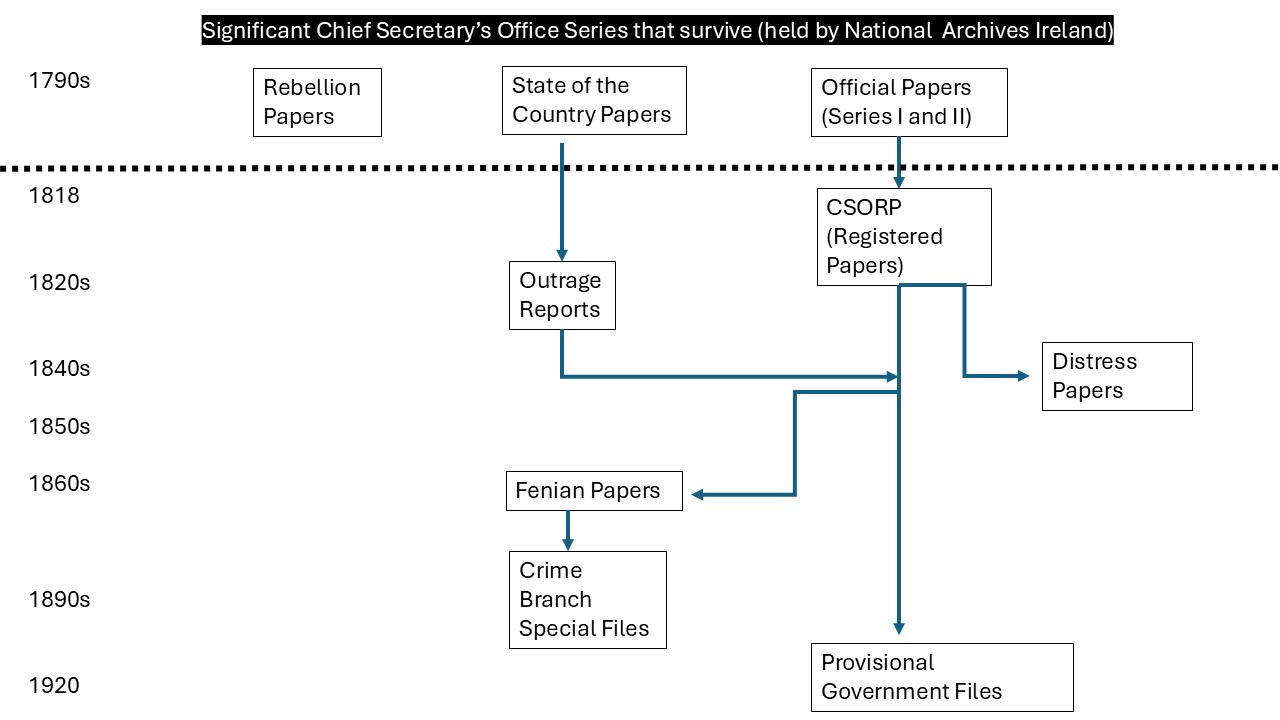

The granting of Catholic Emancipation in 1829 and the Whigs’ return to power in November 1830 marked a profound transformation in Anglo-Irish relations. The decade that followed saw a broader shift in political, administrative, and even cultural attitudes toward Ireland. Meanwhile, in the wake of emancipation and increased oversight from London, the permanent bureaucracy in Dublin had to become more attuned to Irish needs. It is perhaps not a coincidence that the majority of Chief Secretary’s Office records destroyed in the Public Record Office in 1922 dated from before the 1830s, reflecting new, rationalized systems of administration and record keeping, and a tendency for later records to be retained in Dublin Castle or Whitehall.

Staff and Structure

The structure of the Chief Secretary’s Office fluctuated over time. Before the 1770s, the Castle administration consisted of the Lord Lieutenant, and then two secretaries who were clearly distinguished by rank, the senior being known as the ‘first’ or ‘chief’ secretary, and the junior as the second or ‘Ulster’ secretary. The titles derived from how the two secretaries were paid. Instead of receiving salaries, the chief secretary received the fees from civil and ecclesiastical business arising in the provinces of Leinster and Connacht while the second secretary received fees on business in the provinces of Ulster and Munster, leading to him being known as the ‘Ulster secretary’. This arrangement was abolished in 1777, with the office divided into two branches, the civil and the military departments, and with the post of Ulster Secretary abolished. Instead, the two departments were each overseen by an undersecretary. These arrangements remained substantially unchanged for the next several decades, the only significant innovation being the creation of a yeomanry section in 1797 (headed by a senior clerk rather than an undersecretary) and an office of assistant under-secretary for the civil department in 1799, who had responsibility for certain legal business. The first big change to this arrangement occurred in 1818, when the civil and military departments were merged and subsequently overseen by a single undersecretary. In 1852, the Chief Secretary’s Office was once again divided into two divisions, administrative and financial. In 1904, a judicial division was created, along with a ‘land and works’ division, although the latter was merged with finance in 1911.

The size of the Chief Secretary’s Office staff remained small for the period 1770-1830. In addition to the Chief Secretary and two under-secretaries, there were at least six clerks although the exact numbers or identities of the clerical staff remain hard to know. In general, only those officials whose appointment was by letters patent were recorded in accounts such as the Liber Munerum. It seems no systematic record of clerical or junior staff appointments was ever made, or at least not one that survived the destruction of 1922. What is certain is that the number of personnel employed by the chief secretary was less than twenty individuals. In 1830, in addition to the Chief Secretary and Undersecretary, the office employed 19 clerks, including a chief clerk, three senior clerks, a librarian and a registrar.

In addition to the staff in Dublin Castle, during the eighteenth century there was also a ‘resident secretary’, permanently based in London and who aided the Lord Lieutenant’s with necessary business in England, such as securing the passage of Irish parliamentary bills through the British privy council. The Irish Office served as a clearing house for all Irish affairs sent to the viceroy while he was in England and for communications between the viceroy and ministers when he was in Ireland. Between 1740 and 1772, the resident secretary was Sir Robert Wilmot, and the office quickly declined in importance following Wilmot’s resignation, being abolished at the time of the Union in 1800. The functions of the resident secretary were replaced in the nineteenth century by the Irish Office, set up to provide a base for the Chief Secretary when he was in London, and to handle the necessary correspondence.

Location

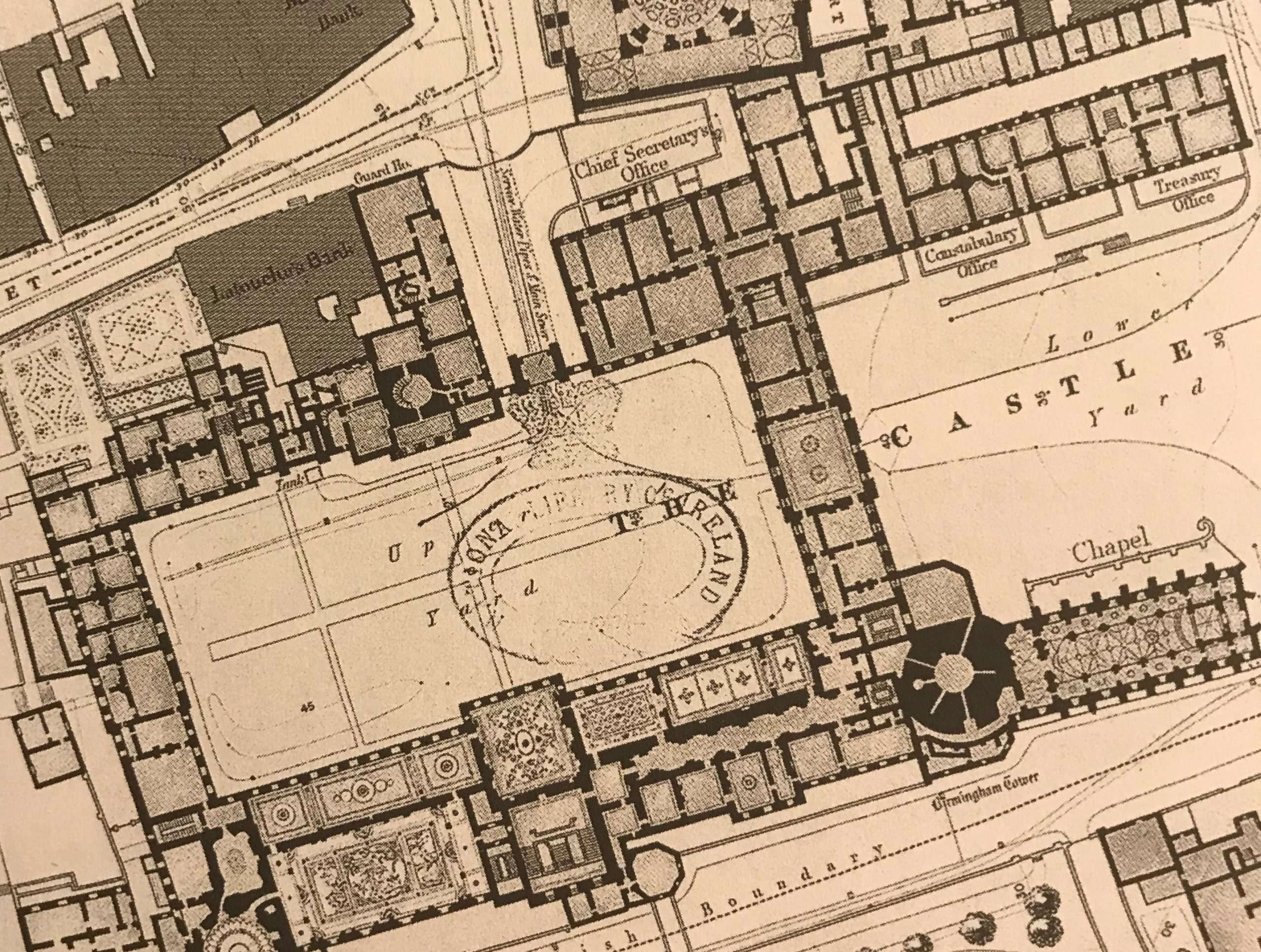

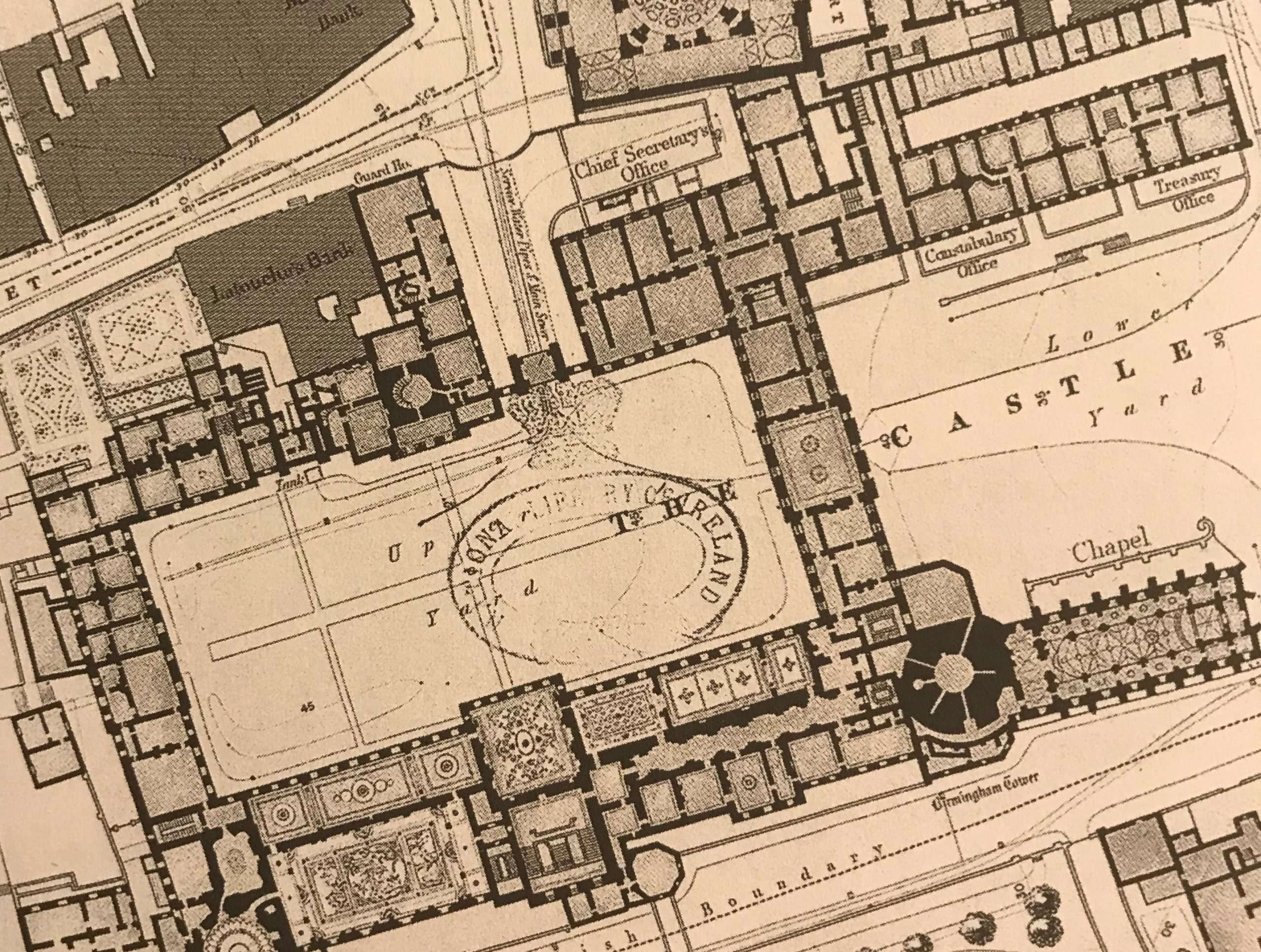

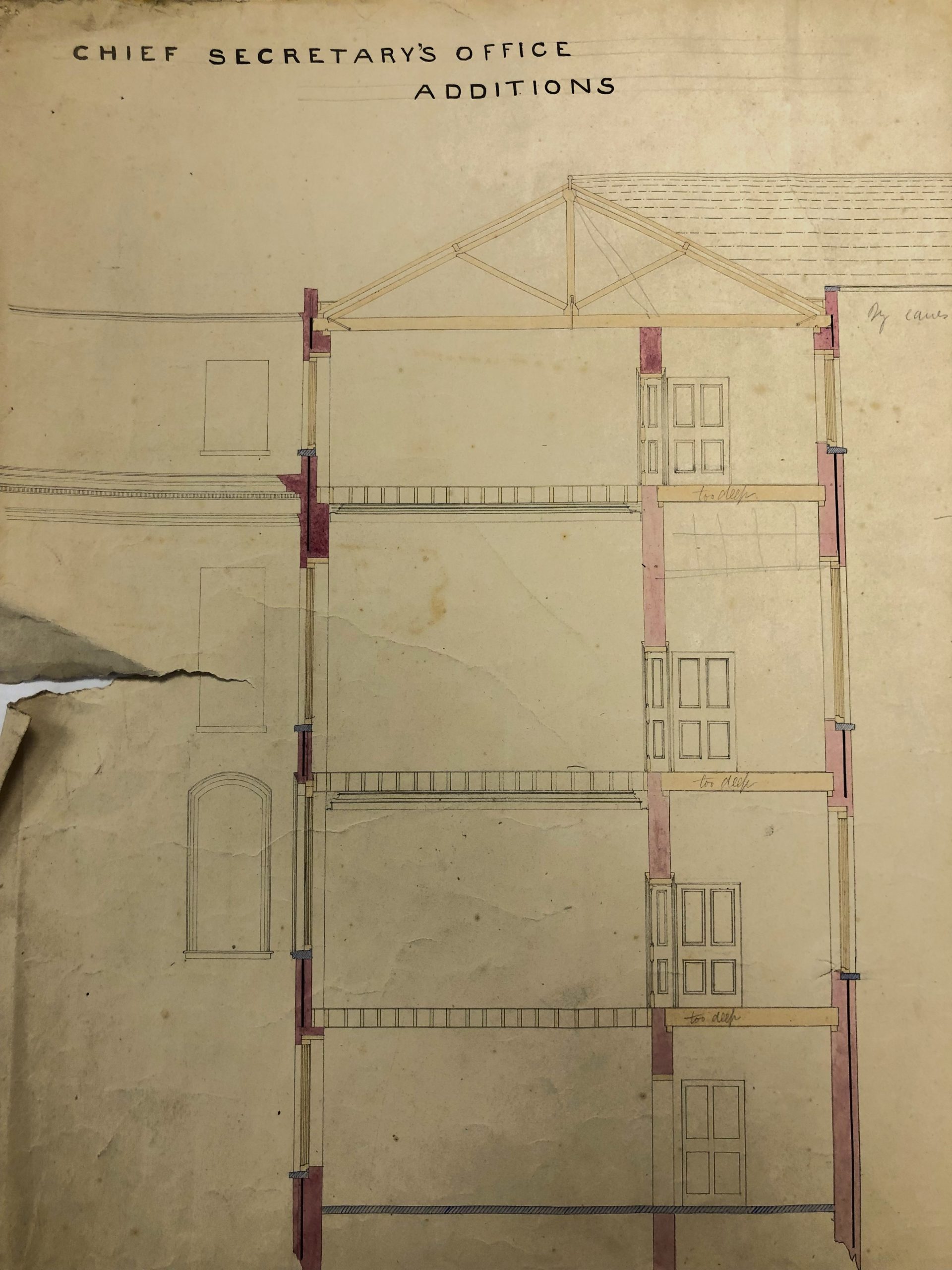

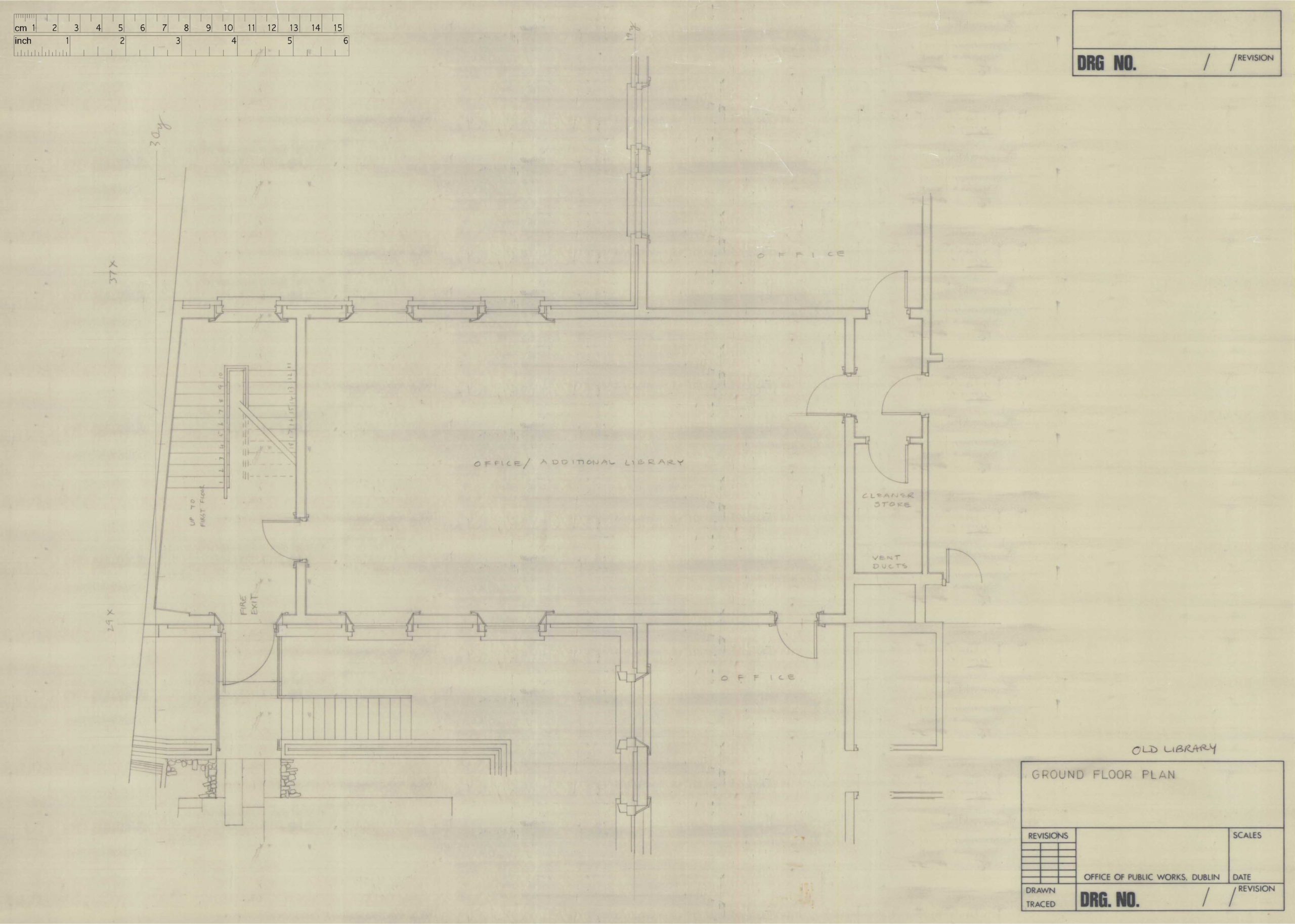

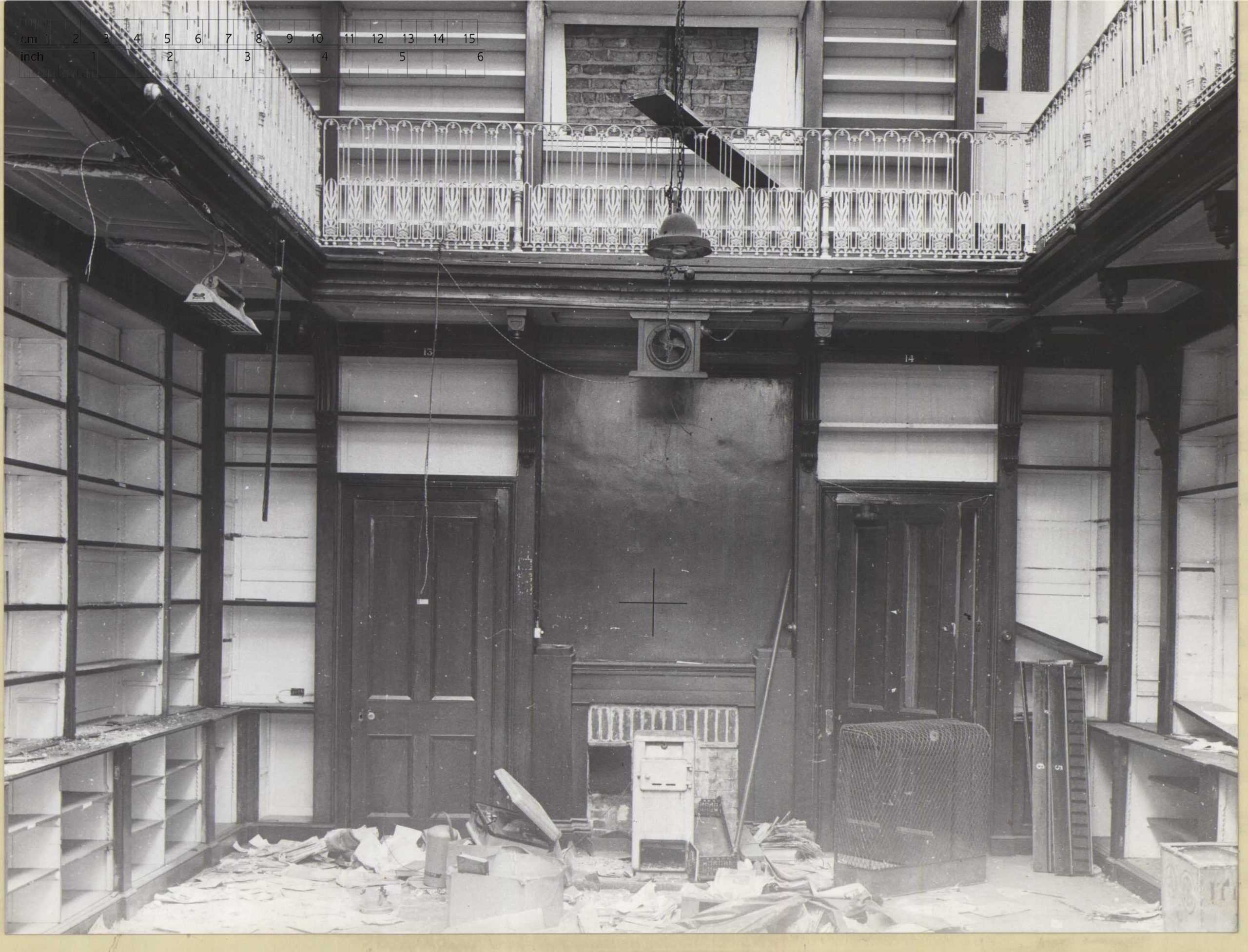

The Chief Secretary’s Office was located within the Upper Yard of Dublin Castle. Following a number of refurbishments in the 1740s, the block that contained the Chief Secretary’s Office was rebuilt on the former site of the Powder Tower, in the north-east corner of the upper yard. Broadly speaking, this is where the Office remained for the remainder of its history, although the size and layout of the office changed over time. While we do not have any graphic depictions of the interiors, several accounts make reference to a busy and crowded location. In 1797, Charles Teeling, attempting to see Edward Cooke, the civil undersecretary, described how he made his way ‘through the circle to the ante-chamber of the secretary, which was crowded with needy expectants, bustling magistrates, and the numerous parasites that always flutter around the purlieus of office’. [Charles Teeling, History of the Irish Rebellion of 1798: A Personal Narrative (1828)]

It seems the space of the office expanded in the early nineteenth century, in order to accommodate the growing number of clerks, as well as a burgeoning Chief Secretary’s library. By the late nineteenth century, the Chief Secretary’s Office sat at the heart of a complex of institutions, most of which had a role in policing or justice. This was described in 1909 by one lawyer and historian: ‘the Chief Secretary’s room opens into the Under-Secretary’s, and the Under Secretary’s into the Assistant Under-Secretary’s. In the passage outside to the right is the Council Chamber where the Privy Council assembles as occasion demands. At the other end of the passage to the right are the Law Officers’ departments. The Attorney General and Solicitor-General sit in one room, and this opens into the Lord Chancellor’s room. A short stone staircase, outside the Chancellor’s room, leads to the apartments (opening into each other) of the Inspector-General and Deputy Inspector-General of the Constabulary. In the same block of buildings in which is the Chief Secretary’s room, the Commissioners of Prisons are housed… Thus it will be seen that the forces of law and order are geographically concentrated in the Castle.’ [R.B. O’Brien, Dublin Castle and the Irish People (1909)]

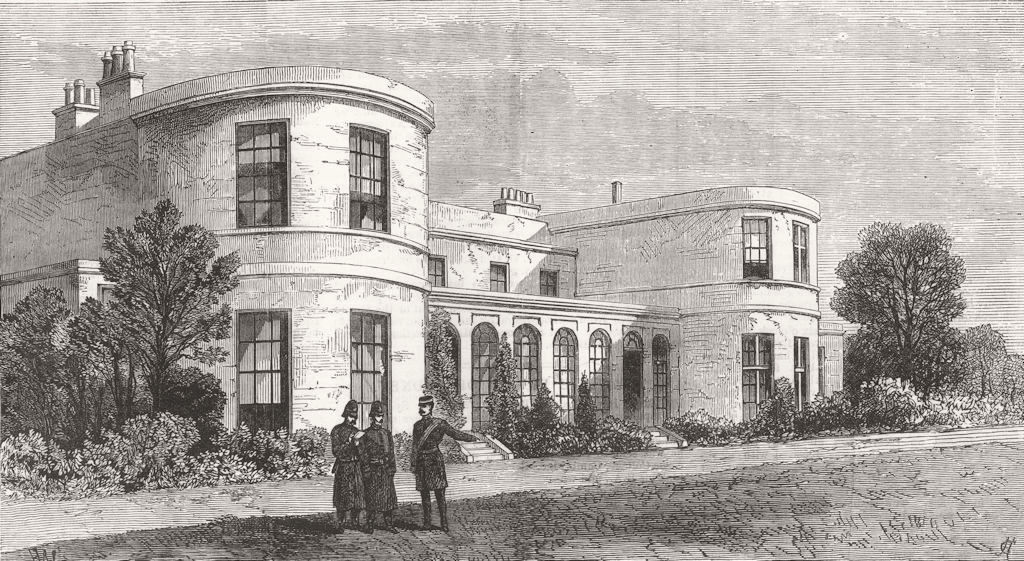

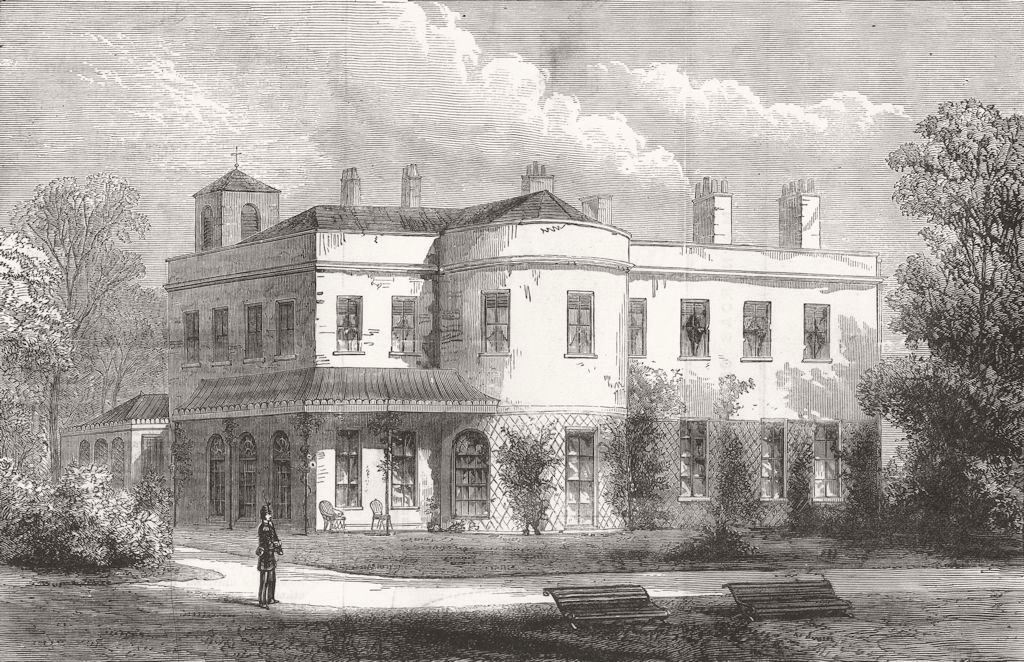

Outside the grounds of the Castle, there were other sites linked to the Chief Secretary’s Office. Much like the viceroy, the Chief Secretary also had residence in the Phoenix Park. The Chief Secretary’s ‘lodge’ was Deerfield House, constructed by a Chief Secretary, Sir John Blaquiere, in 1774 and subsequently purchased by the government. The building now serves as the official residence of the United States Ambassador to Ireland. After 1782, the civil under-secretary also had a residence in Phoenix Park, known as Ashtown House. This building no longer remains having been demolished in the 1980s, revealing that the residence had actually been constructed around an older castle, which can be found next to the current visitors centre in the park.

The Chief Secretary’s Library

An important resource within Dublin Castle was its library. Surprisingly, there was no dedicated library in the Chief Secretary’s Office until the 1810s, when Sir Robert Peel commissioned the Irish topographer and statistician William Shaw Mason to assemble a ‘select Irish library’ for him. Mason sought out works that provided ‘general views of the circumstances of the country,’ drawing from the principal writers on the leading subjects and events of the several periods, from the earliest extant to the year 1820.’ The result was an impressive collection of around 170 volumes, including both books and pamphlets.

However, Peel was a clear example of how intelligence and education don’t always lead to greater understanding—they can just as easily reinforce existing prejudices. Despite his wide reading of this carefully curated library on Ireland, he largely echoed the long-standing views held by British politicians.

Peel’s library did not remain in Dublin Castle for long, eventually making its way to the library of the British House of Lords. Nonetheless, a substantial reference library for the Chief Secretary’s Office was developed over the nineteenth century. This collection includes materials dating back to the sixteenth century, with thousands of volumes of parliamentary records, books, maps, newspapers, manuscripts, prints, and pamphlets. Following Irish Independence in 1922, Dublin Castle was transferred to the Irish Free State. The Chief Secretary’s Office Library collection was transferred to the newly established Oireachtas Library in Leinster House in 1924. It has been held by the Oireachtas Library since and the vast majority of the collection has been digitised and made available via the searchable catalogue:

The Houses of the Oireachtas Digital Library

The Houses of the Oireachtas Digital Library

Archival History

Despite the importance of the lord lieutenant and his administration, for many years there was a tendency for the holders of the office to take official documents away with them, most viceroys considering these letters to be their personal property. This was sufficiently problematic that in 1702 an Irish State Papers Office was created to preserve the records produced by the administrations of successive lord lieutenants. These records were initially stored in the Birmingham Tower; however, following a report by the Irish Record Commissioners in 1812, this was found to be unsuitable. A new repository was then created by refitting the Wardrobe Tower. In the nineteenth century, the Chief Secretary’s Office regularly transferred materials to the State Paper Office, where they were to remain until the records were 50 years old, at which time they were to be transferred to the Public Record Office.

The destruction of the Public Record Office of Ireland in 1922 had a catastrophic impact on the surviving records of the Chief Secretary’s Office. The fire obliterated vast quantities of official correspondence, memoranda, and administrative records that had been systematically transferred to the PROI over the previous century. Among the lost materials were critical documents that would have provided unparalleled insight into the relationship between Dublin Castle and Whitehall, including intelligence reports, legal proceedings, and high-level political correspondence. The destruction of these materials has significantly hampered scholarly efforts to reconstruct the day-to-day mechanics of governance in Ireland during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

At the time of their transfer to the PROI, it was described how ‘many of these letters, though written on public affairs, have the character of private correspondence, for they deal fully as much with the ordinary circumstances of the day as with public business.’ A later guide to the PROI would describe how ‘in order to possess the clue to the government of the country,’ this series ‘possesses high value,’ containing letters from all of the major British parliamentary figures of the day’. The records destroyed in 1922 included crucial series that would have illuminated the mechanics of government between Dublin and London in the early nineteenth century. For example, one of the significant losses was the Departmental Correspondence (British) series (1683–1759), which contained letters from Lords Lieutenant and their secretaries when in England, as well as correspondence from other departments about civil and military matters. Another major casualty was the vast Official Papers, 1760–1830 series, which included ‘letters to the Irish Government from Public Departments or officials in England and Ireland, and papers connected therewith.’

Further Reading

Edward Brynn, Crown and Castle: British Rule in Ireland 1800–30 (Dublin, 1978).

Seán Duffy, John Montague, Kevin Mulligan & Michael O’Neill, Dublin Castle: From Fortress to Palace Volume 1: Vikings to Victorians. A history of Dublin Castle to 1850 (Wordwell, Dublin, 2022).

J. L. J. Hughes, ‘The Chief Secretaries in Ireland 1566-1921’, Irish Historical Studies, 8:29 (Mar., 1952), pp. 59-72.

K. Theodore Hoppen, Governing Hibernia: British Politicians and Ireland 1800-1921 (Oxford, 2016).

Brian Jenkins, Era of Emancipation: British Government of Ireland 1812-30 (Montreal and Kingston, 1988).

Edith Mary Johnston, Great Britain and Ireland, 1760-1800; a study in political administration (1963).

R.B. McDowell, The Irish Administration, 1801-1914 (London, Routledge, 1964).

J.C. Sainty, ‘The Secretariat of the Chief Governors of Ireland, 1690-1800’, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature, Vol. 77 (1977), pp. 1-33.