via the Knowledge Graph

Explore People

Explore People Introduction

The Chief Secretary’s Office was the nerve centre of British administration in Ireland during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Serving as the Lord Lieutenant’s principal advisor, the Chief Secretary managed a complex administrative network, overseeing government departments, supervising Ireland’s military establishment, and managing the administration of justice. The Chief Secretary’s Office also served as the main channel of communication between officials in Dublin and London, mediating between the two to align Irish policy with British priorities. This curated collection reunites surviving official papers and personal correspondence of Ireland’s Chief Secretaries, providing rare insight into the executive government at Dublin Castle. From intelligence gathering and countering conspiracies to routine tasks such as managing state finances and public services, these papers reveal how the machinery of government operated during a time of significant political and social change. By drawing together the scattered papers of Ireland’s Chief Secretaries, this project reconstructs elements of a lost collection once considered among the richest in Ireland’s public records. It provides an indispensable resource for understanding the complexities of Irish governance and the strategies employed to maintain authority in an age of uncertainty.

Michelangelo Hayes, St Patrick’s Day Military Parade at Dublin Castle (1844).

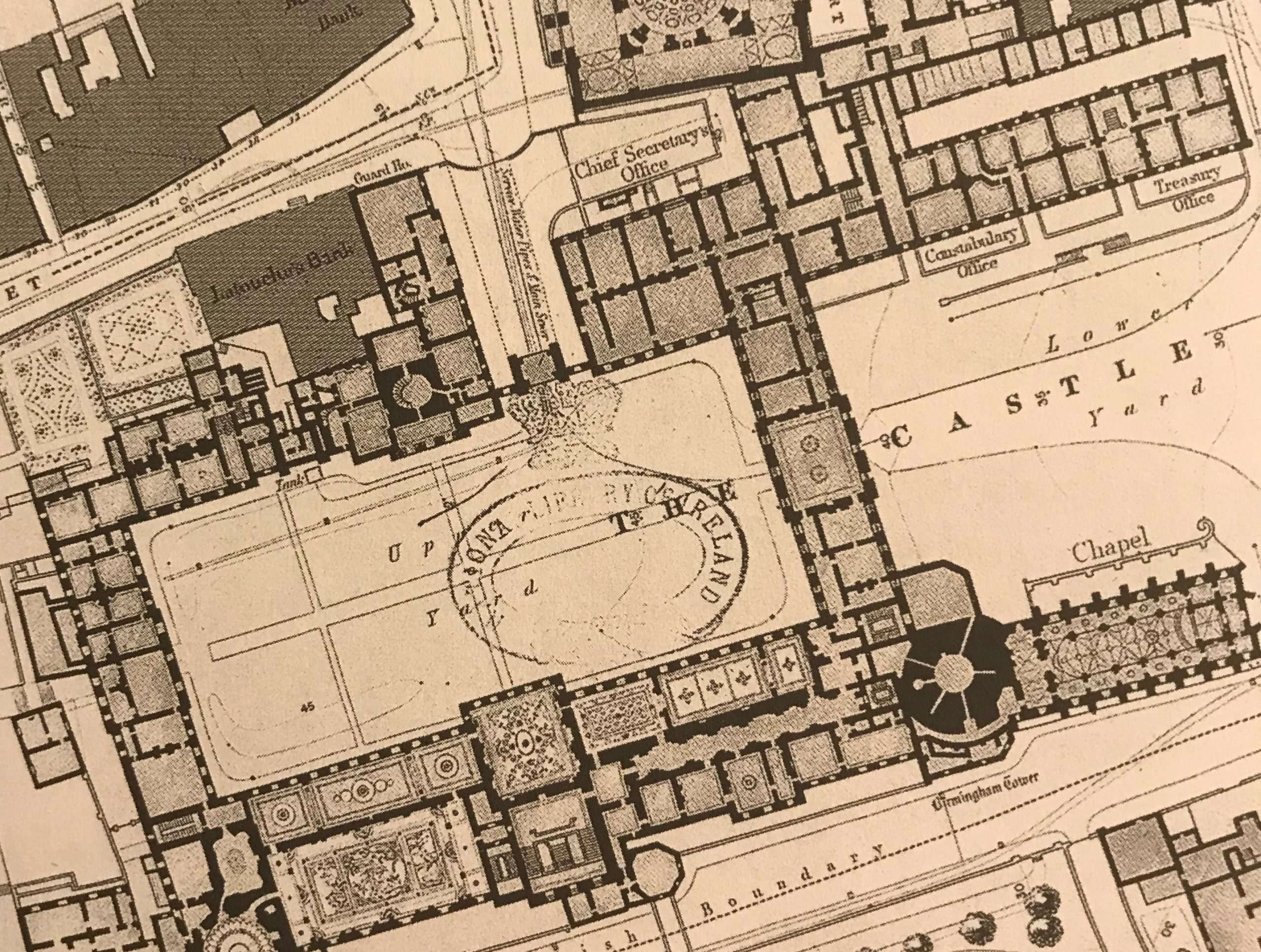

From the sixteenth century, the English (later British) government in Ireland was based in Dublin Castle, overseen by a viceroy or lord lieutenant. Each lord lieutenant had a chief secretary—originally a personal assistant responsible for organizing and implementing policy. However, in the aftermath of the Williamite Wars (1690s), the Chief Secretary’s role expanded into a distinct administrative office overseeing central government functions. By the eighteenth century, the Chief Secretary controlled a department in Dublin comparable to the secretaries of state’s office in London, earning descriptions as the “nerve centre” and “mainspring” of Irish administration. The office became the main channel for implementing the lord lieutenant’s directives and carried out many functions that, in Britain, fell under the Home Office. The Chief Secretary oversaw military and civil expenditure in Ireland and coordinated communication between government departments in London and their counterparts in Dublin. By 1800, the office supervised 21 other Irish government departments.

Beyond administration, the CSO played a crucial role in justice. It oversaw local magistrates, corresponded with justices of the peace, received petitions from prisoners, and conveyed orders from the attorney general. In some cases, it exercised direct control, particularly when the lord lieutenant used his power of pardon or imposed direct rule over “disturbed” regions under the Insurrection Acts. At the same time, the Chief Secretary was a key parliamentary figure, responsible for managing the Irish House of Commons and ensuring the passage of key legislation—especially financial measures known as “money bills”—on behalf of the administration.

Following the Act of Union (1801), the CSO’s role shifted dramatically. With the abolition of the Irish Parliament, the Lord Lieutenant and Chief Secretary became the primary representatives of British rule in Ireland. The Chief Secretary now spent much of the year in London, defending Irish policy in the British House of Commons, while the Lord Lieutenant remained in Dublin. This shift made the Chief Secretary the dominant political figure in Irish administration. As the nineteenth century progressed, the CSO’s responsibilities grew in response to post-Union challenges, particularly agrarian unrest and the campaign for Catholic emancipation. The eventual passage of the Catholic Relief Act (1829) marked a turning point, highlighting the office’s central role in navigating Ireland’s turbulent political landscape.

What can I find here?

This collection offers a curated selection of transcriptions that serve as substitutes for the lost records of the Chief Secretary’s Office (c.1770–1830). The transcriptions are organized around a series of themes that reflect the key issues the office addressed, including:

- Catholic Affairs

- Defence

- Disturbances

- Economy

- Established Church

- Finance

- Law

- Militia and Yeomanry

- Parliament

- Presbyterian Affairs

These themes are adapted from the CSO’s own departmental filing system, as described in Herbert Wood’s Guide to the Records Deposited in the Public Record Office of Ireland (1919). Thus this method of organization mirrors the internal arrangement of the destroyed archive and aids users in navigating the collection. The transcriptions have been drawn from a range of sources—including state paper collections held in London and Dublin (such as the Home Office (Ireland) Papers and Rebellion Papers) and private papers of former chief secretaries or lords lieutenant now housed in repositories like the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland, the British Library, and the National Library of Ireland. Selected to illustrate the CSO’s policies and procedures from 1770 to 1830, most items are letters exchanged by the Chief Secretary or his under-secretaries, while others include reports and digests prepared for London ministers, or opinions from senior officials such as the Irish Attorney General or Lord Chancellor. Each transcription provides the source repository, reference number, and, when available, a link to the digitized original in the Virtual Record Treasury.

Within each theme, the transcriptions are listed chronologically by year, month, and date. In addition, users can utilize the search bar at the top of the page to explore both these transcriptions and a broader array of CSO materials available on the Virtual Record Treasury, making it easy to locate specific documents or explore topics of interest.

These materials provide an insider’s look at how Ireland was managed and how political decisions were made during some of the country’s most significant events—such as Irish Legislative Independence in 1782, the 1798 Rebellion, the Act of Union in 1801, and the fight for Catholic Emancipation in 1829. In doing so, the collection offers a valuable window into how this office helped shape Ireland’s history during these defining years.