Women in the Guild of St Anne

A Closer Look at Our Media Gallery

RIA GSA/17/54, Deeds of the Guild of St Anne, 43 Elizabeth I, Item 54 (8 December 1600) - The founding charter of the Guild of St. Anne provides for a guild comprising both men and women dedicated to St. Anne, the mother of Mary. The leadership of the Guild throughout its history, particularly the master and two wardens of the Guild, was predominantly male, however, the Guild had many female members, and by the late 16th century several women were taking an active role in Guild governance, acting as witnesses on legal documents.

View this item

RIA GSA/6/38, Deeds of the Guild of St Anne, 15 Richard II, Item 38 (20 April 1392) - In medieval English law, a woman's right to own and control property was curtailed and controlled by the men in her life: first her father, then her husband. If she was widowed, she then was entitled to a dower that had been given to her at marriage and usually one third of her husband's property. Widows act as executrices of their late husbands' estates, frequently with a male co-executor, or they act alone to confer land belonging to their late husbands. Women acting alone, even as wealthy widows, were exceptions to the normal rule of law.

View this item

RIA GSA/9/15, Deeds of the Guild of St Anne, 6 Henry VI, Item 15 (4 February 1428) - In the late Middle Ages, women's seals and marks were subject to extra scrutiny in the same way the seal of someone new to the Dublin community or someone who was otherwise inactive in civic life or in property transactions might be scrutinised. When a grantor's seal was largely unknown, the Seal of the Provostship of Dublin was frequently used as a further means of authentication, regardless of the gender of the grantor. The infrequency of legal transactions by widows meant that deeds in which the grantor is a widow were more likely to have the extra authentication of the Seal of the Provostship.

View this item

RIA GSA/9/44, Deeds of the Guild of St Anne, 13 Henry VI, Item 44 (15 January 1435) - Most seals were relatively small, usually less than 1 cm. in diameter. They were formed from impressing a metal seal matrix into a ball of warm wax. The matrices themselves were on rings or other small metal objects. Seals were affixed to strips of parchment that had been made either by slicing horizontally most of the way across the bottom of a document, or, more commonly, by folding up the bottom 1-3 centimeters of a document, cutting a 1-3 cm. slit through both layers, and threading a strip of scrap parchment through the slit.

View this item

RIA GSA/17/40, Deeds of the Guild of St Anne, 39 Elizabeth I, Item 40 (12 October 1597) - In the late 16th century, these seals give way to signatures, marks, or initials written in ink on transactions, and in the case of marks and initials, identified with a full name by the document's scribe. These marks were further authenticated by the addition of seals in the traditional manner.

View this item

RIA GSA/25/1, Deeds of the Guild of St Anne, 9 George I, Item 1 (13 February 1723) - By 1723, the heavy wax seals hanging from the bottom of the parchment have been done away with in favor of an image impressed into several drops of wax poured directly on the document itself.

View this item

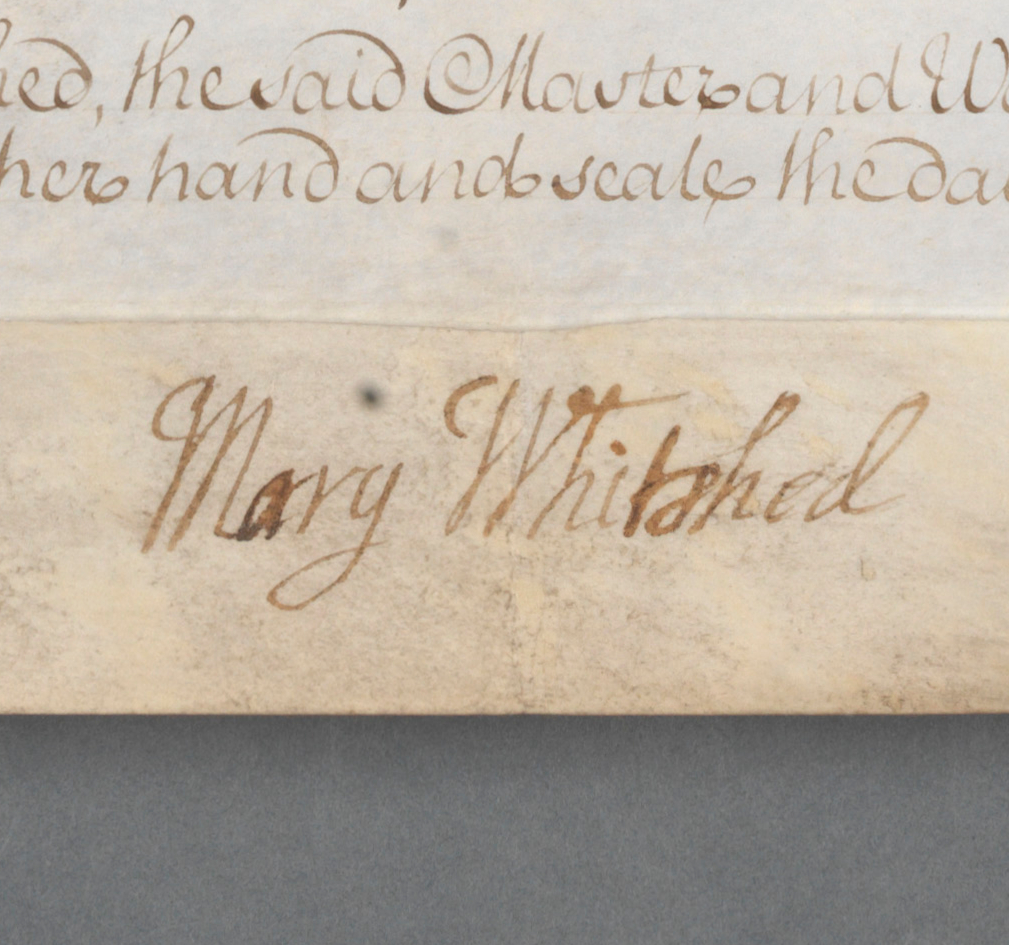

RIA GSA/5/8, Deeds of the Guild of St Anne, 4 Edward III, Item 8 (7 July 1330) - The images on seals, when they can be determined, vary greatly, from religious iconography such as Mary and the Christ child on the seal of Margery, daughter of John de Stradbally, to initials like the crowned B of Alicia Ballybyn, to the Classical-looking profile of a young man on the seal of Alson FytzSimon, and the family arms on the seal of Mary Whitshead.

View this item

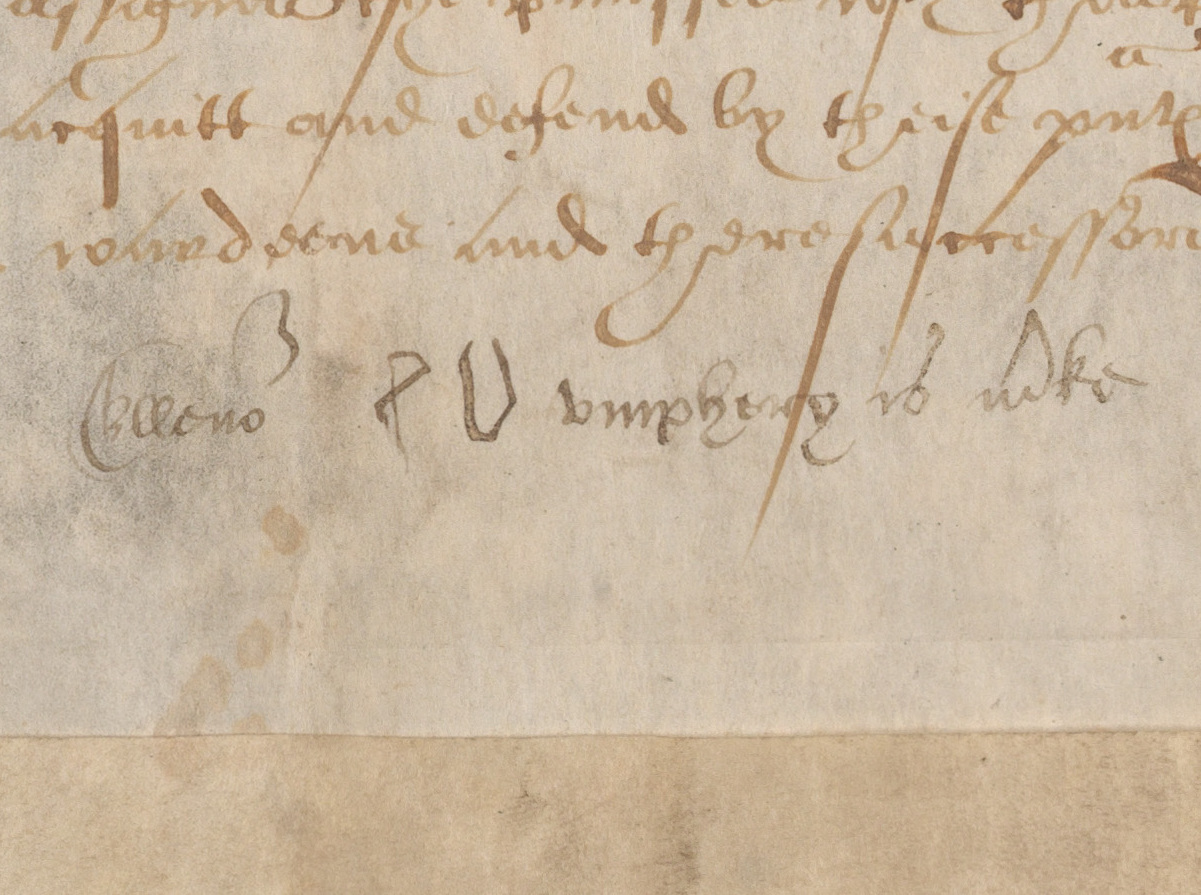

RIA GSA/25/1, Deeds of the Guild of St Anne, 9 George I, Item 1 (13 February 1723) - Initials and signatures demonstrate a range of writing proficiency from the tenuous initials of Elinor Umphrey which appear to be an unpractised attempt to copy letter forms, to the highly confident signature of Mary Whitshead.

View this item