Women in Rebellion: Recovering Female Voices in the 1798 Rebellion Papers

in partnership with the National Archives of Ireland

This letter, written by Lady Louisa Connolly from Castletown House in July 1798, offers a rare glimpse into the informal but influential role played by elite women during the 1798 Rebellion. Louisa Connolly (1743–1821), one of the Lennox sisters and wife of MP Thomas Connolly, belonged to Ireland’s political aristocracy. Despite her status, her correspondence shows how women like her could intervene in matters of justice and clemency at critical moments. In this letter, she writes to Lord Castlereagh, the Chief Secretary, on behalf of Nicholas Murphy, who claimed he was imprisoned simply for sheltering the fugitive Lord Edward Fitzgerald, a leader of the United Irishmen and Connolly’s nephew by marriage. Lady Louisa, cautious about being misled, nonetheless advocates for Murphy’s release, suggesting he acted from compassion for her nephew, rather than political conviction. She asks Castlereagh to inquire into the case and recommends Murphy for bail. She also reports a broader change in local sentiment, noting that many in Kildare formerly involved in rebellion now longed for peace and reconciliation. This letter reveals the power of personal influence, the moral complexities of loyalty, and the ways family and political crisis could intertwine during this tumultuous period.

View this item

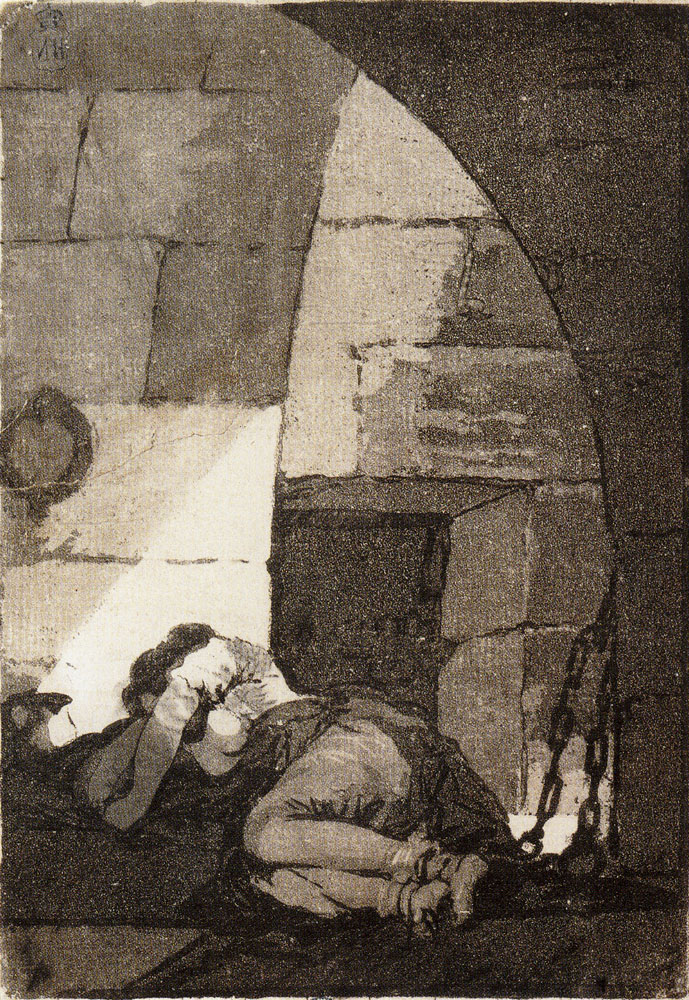

This court martial record from Carlow, dated April 1799, preserves the harrowing testimony of Margaret McIvers, a young woman who survived the murder of her family during a rebel attack in Kildare the previous year. Her account stands out not only for its emotional weight but also for the window it offers into women’s experiences of the 1798 Rebellion and its violent aftermath. John Whelan, the accused, was charged with involvement in the attack on the home of Hannah Manders on 24 September 1798. Five people (including four women and a servant) were reportedly killed and their bodies burned. McIvers, Manders’s niece, survived by hiding in a limekiln. Her detailed testimony recounts the violence in chilling detail, from the attempts to flee to the horror of seeing her bedridden aunt murdered in a garden. Between 1798 and 1801, court martials became the main forum for prosecuting suspected rebels. Though these military tribunals were criticised for bypassing legal safeguards, they inadvertently created one of the most significant archives of female testimony in Irish history. As the historian Thomas Bartlett has noted, they represent the largest such body of material since the 1641 Depositions. This document reveals how the upheaval of rebellion brought women’s voices into the public record: testimonies of survival, loss, and courage, told in the face of trauma and under the shadow of military justice.

View this item

The case of Catharine Kelly, tried before a general court martial in Clonmel on 28 March 1799, is a rare and revealing episode in the history of the 1798 Rebellion’s aftermath. It is the only known instance in which a woman appeared as the primary defendant in a military trial during this period. Kelly was charged with involvement in the murder of John Delahunty, allegedly committed with ‘divers other persons not yet taken’ near Clonmel. She denied the charge, stating only that Delahunty’s body had been removed from her husband’s house by two men. With no witness present to testify, the case collapsed. Although acquitted, Kelly was nonetheless bound over for possible future testimony, which suggests that official suspicion persisted. Her trial is significant not only for its rarity but also for what it reveals about how women were viewed in the context of rebellion. While women more often appear in court martial records as witnesses or victims, Kelly’s prosecution shows that some were also seen as active participants or as potentially complicit in revolutionary violence. The state’s decision to prosecute a woman for capital offences demonstrates a recognition of the key role played by women during the rebellion.

View this item

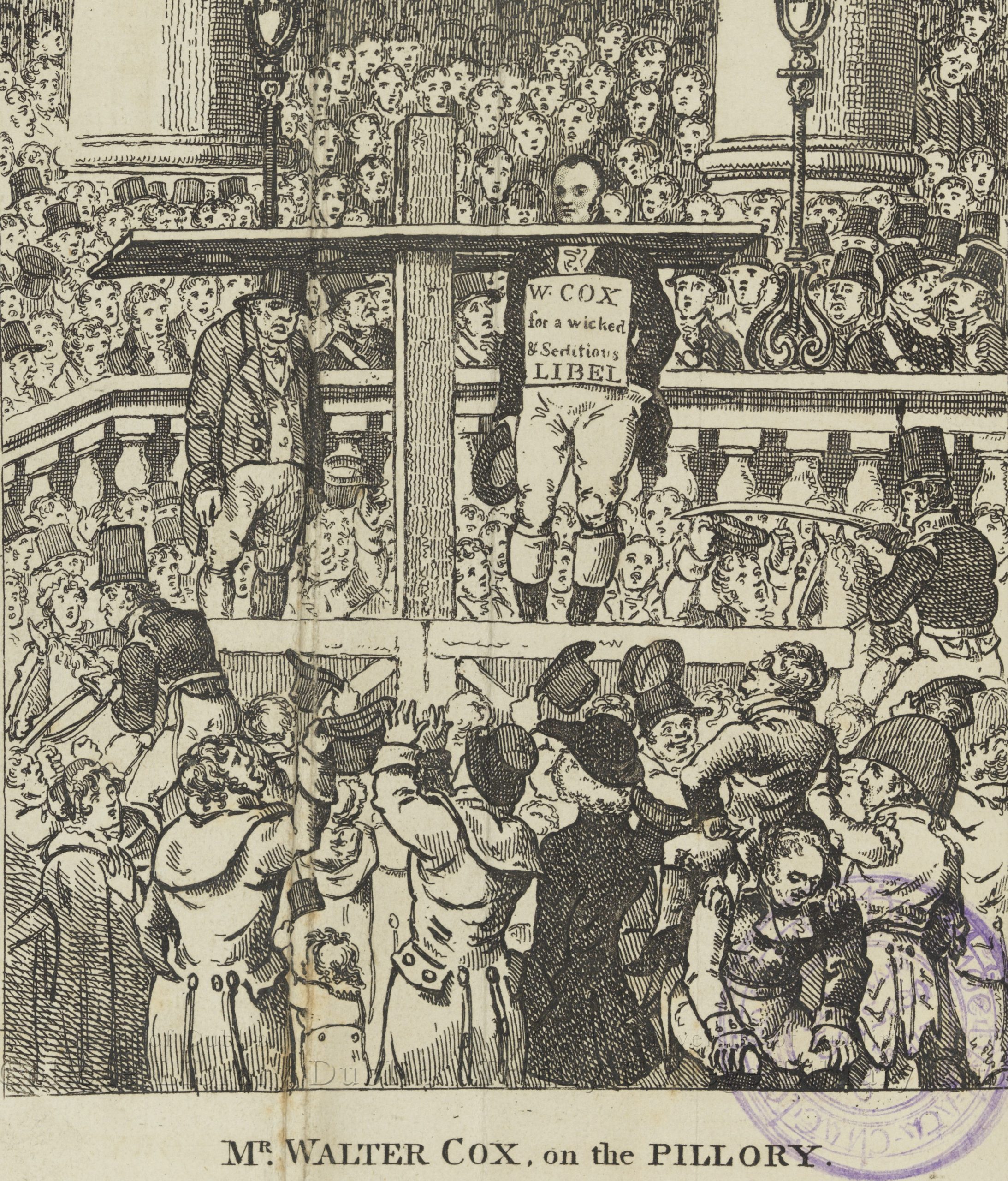

This remarkable document from 1802 records a rare and explosive accusation: a wife denouncing her husband for sedition. The man in question, Walter ‘Watty’ Cox, was a well-known radical, publisher, and former political prisoner. His wife’s statement accuses him of plotting against the Crown, speaking violently about the King, and conspiring with a network of fellow subversives whom she names. Watty Cox was already very familiar to the authorities. A former United Irishman, he had been responsible for one of the most notorious publications of the 1790s, the Union Star, a broadside which listed the names of alleged government informers and called for violent overthrow of the government. From 1807 to 1815, he also edited The Irish Magazine, a periodical known for its fiery rhetoric and satirical style. In this letter, Mrs Isabella Cox reports her husband’s claims that Ireland was ready to rebel again and that recent peace between Britain and France was merely part of Napoleon’s strategy, one that would include an Irish invasion. She describes her husband attending secret ‘lodges,’ meetings of rebels she suggests were disguised as Freemason or Orange gatherings. While the precise details are unclear, it is obvious that the marriage between Walter Cox and Isabella was an unhappy one, with ‘Watty’ known for treating his wife poorly. The couple’s only child (also named Walter) would die in 1814, aged only 12. Whether motivated by fear, domestic hatred, or political conviction, Mrs Cox’s intervention offers a glimpse into the personal dimensions of rebellion.

View this item

This affectionate letter, written by Lady Pamela Fitzgerald to her husband Lord Edward Fitzgerald in early 1797, offers a rare glimpse into the private life of one of the United Irish leadership’s most renowned couples. Pamela, born Pamela Syms and possibly the unacknowledged daughter of the Duc d’Orléans, married Lord Edward in 1792. By 1797, Lord Edward was deeply engaged in the United Irish movement and its planning for a popular insurrection. Writing from Castletown House, Pamela contrasts the cold artifice of 'beautiful houses' with the warmth and equality of simpler homes, a sentiment that reflected her and Lord Edward’s shared sympathy for republican ideals. The letter is rich in glimpses of their circle, from family members like Lucy and Aunt Sarah to political confidants like O’Connor. Pamela’s observations are interwoven with domestic detail, including the health and charms of their young daughter ‘little Pam’, her ‘democratic’ tea-drinking, and references to reading Plutarch. In these small details, the letter reveals how love, politics, and shared intellectual life were deeply intertwined in their marriage. Like many women in the Rebellion Papers, Pamela’s words show that private correspondence could carry both personal affection and political meaning.

View this item

This letter from Mary Ann McCracken to Thomas Russell, offers a deeply personal account of the execution of her brother, Henry Joy McCracken. More than a private expression of grief, it is a political document, rich with testimony of how the Rebellion affected families and friends. Henry Joy McCracken, a founding member of the United Irishmen in Belfast, helped lead the failed uprising in Antrim in June 1798. He was captured on 7 July, swiftly tried by court martial, and then executed. Mary Ann remained at his side throughout and here recounts his calm demeanour, the flawed testimony used against him, and the military’s refusal to allow him a final speech. She was forcibly removed from the scaffold, denied even the consolation of a last farewell or a lock of her brother’s hair. The letter is addressed to Thomas Russell, McCracken’s close friend and fellow United Irishman, then imprisoned in Dublin. Mary Ann’s tone is composed but resolute, balancing sorrow with a clear sense of injustice. She memorialises her brother as ‘the idol of the poor,’ whose murder was both cruel and politically foolish. Significantly, Mary Ann’s activism did not end with the rebellion. In later decades, she became a prominent reformer in Belfast, campaigning against slavery, advocating for education and workers’ rights, and supporting the city’s poor. Her commitment to justice remained rooted in the same ideals that shaped her brother’s final stand.

View this item

This heartfelt petition, written by Mary O’Neil of Westport after the 1798 Rebellion, highlights the often-overlooked suffering of soldiers’ families during and after the conflict. Addressed to Irish MP Denis Browne, it recounts the loss of her husband, Serjeant Barney McMahon of the Armagh Militia, who died following an encounter with United Irish forces in Ballybay, County Monaghan. According to O’Neil, McMahon was deployed with just twenty-one men and two sergeants against a force of over a thousand rebels. Though he survived the fighting, he died shortly after ‘by the dint of firing and exerting himself.’ His death left Mary alone in unfamiliar surroundings, holding her infant and without any means of support. With no officers available to assist her, Mary learned from another sergeant that Lord Gosford, the local military commander, had inquired about her. She appeals to Denis Browne to intercede on her behalf, hoping to receive the customary pension of seven guineas granted to widows of loyal soldiers. O’Neil’s petition reflects the precarious position of military wives who bore the emotional and economic consequences of rebellion. Like many in the Rebellion Papers, she used personal testimony and formal petitioning to seek justice and survival. Her voice represents the broader struggles of women navigating loss, displacement, and bureaucracy in the conflict’s shadow.

View this item

This vivid deposition, sworn by Bella Martin before a magistrate in Trim during June 1798, offers an unsettling glimpse into the hidden world of intelligence and counter-insurgency during the rebellion. Martin, originally from Portaferry, County Down, had gained notoriety in Belfast where she worked as a barmaid at Peggy Barclay’s tavern, a meeting place of the United Irishmen known as The Muddler’s Club. While serving drinks, she also informed on the rebels. Her evidence at the County Antrim assizes in 1797 led to the execution of four Monaghan militiamen. In return, the government placed her under protection and sent her south, where she continued to work undercover. By June 1798, she was employed in the household of a Mr Aylmer of Painestown Co. Kildare, father of the rebel commander William Aylmer. Her deposition describes Aylmer’s return from raids, coded correspondence, and a network of rebel support involving Catholic clergy and Dublin allies. She details a mission in which she delivered messages, weapons, and gunpowder to a chapel in Monalvy, where the materials were stored beneath the altar. Martin claimed to act for the public good, not personal gain. Yet her movements through rebel homes, taverns, and military barracks exposed her to serious personal danger and bred rumour, including an unlikely claim that she was Lord Castlereagh’s mistress. She would gain notoriety among later chroniclers of the Rebellion as a ‘Mata Hari’ type figure.

View this item

This final document is a memorial submitted by Jane Montgomery to Lord Cornwallis, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, in the aftermath of the 1798 Rebellion. Such memorials were akin to formal petitions addressed to high-ranking officials, often written in hopes of redress or protection. Writing from County Down, Montgomery claims she was targeted by rebels due to her loyalty to the Crown and her connection to Reverend Mr Molimer, a clergyman she had warned of a planned assassination attempt. In retaliation, she says, two women were bribed to bring false charges against her, leading to her imprisonment for 14 months. During that time, she endured severe physical and financial hardship. An unnamed inspector general, she adds, witnessed her condition and urged her to write to Cornwallis directly. Rather than requesting compensation or position, Montgomery’s appeal is stark: she asks for the means to emigrate to America, the only place she believes she can live without fear. Her petition illustrates how women used formal channels to narrate trauma, assert loyalty, and seek survival.

View this item