State Papers Ireland, 1660–1715

Delving Deeper

The destruction of the Public Records Office of Ireland in 1922 destroyed a huge amount of correspondence. But it was not the only instance where early modern records were destroyed. A fire at Dublin Castle in 1711 consumed volumes of what we would now consider State Papers, largely correspondence dating back to the Restoration of Charles II, as well as the papers that recorded discussions at the Irish Privy Council. But all is not lost. Thanks to what is preserved at The National Archives, UK, we have direct and indirect replacements for what was in Dublin Castle up to 1711 and the Public Records Office of Ireland before 1922. The survival of these replacements in London was haphazard and not guaranteed. But through the diligence of the Keepers of State Papers and their staff, we have a huge resource of material to work with. The next sections will provide detailed information on how the collections were assembled, and who did the assembling.

Cite this Essay: Neil Johnston, ‘State Papers Ireland, 1660–1715 — Delving Deeper’ (VRTI 2025).

Historical Background

The State Papers Ireland [SPI] form a component of a much larger set of records held at The National Archives, UK, known as the State Papers, which are an assembled collection that has been sorted by reign, region, and in some instances, content. The series in its entirety runs from 1509, the first year of Henry VIII’s reign, until 1782, when the duties of the secretaries of state who managed the crown’s correspondence were formally separated, creating the Home Office and the Foreign Office. The collections are divided into State Papers Domestic (meaning England), State Papers Foreign (covering English and British embassies across Europe), State Papers Scotland, as well as any number of other places and topics.

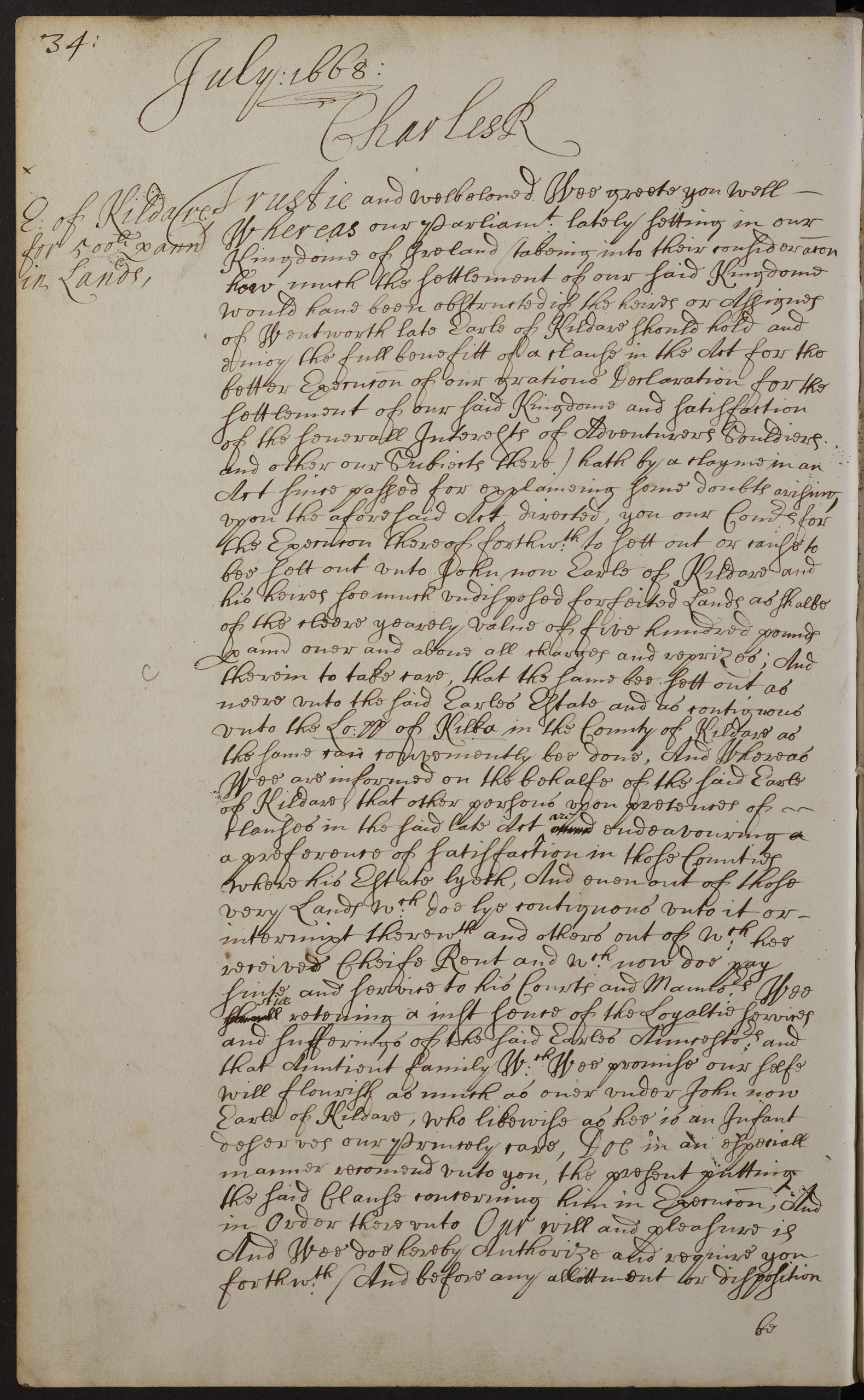

Within this much larger collection, also sit a sub-series called the State Papers Ireland [SPI], which are divided into eight series (SP 60-67), with the largest being SP 63, covering the years 1558-1782. SPI is comprised of more than 480 bound volumes of records that address all aspects of the English administration in Ireland. The core of the collection is letters sent back and forth between senior officials in Dublin and London, which form one of the key primary sources for understanding how early modern Ireland was governed. But alongside official correspondence related to matters of state is a whole miscellany of letters that give us insights into life in Ireland. By the seventeenth century, when most of the island of Ireland was under English control, the monarch was the primary source of justice. As a result, many people directly petitioned the monarch asking for clemency, justice, or assistance.

What makes a State Paper?

It is tricky to define, and there is no hard rule. They are held under the departmental code SP at The National Archives, UK and for the most part, they are an assemblage of letters that arrived into the Secretaries of State at Whitehall or were sent from their offices as part of their work in managing incoming, outgoing, and internal correspondence for the crown. Beyond this, any more precise definition fails to capture the sheer variety of matters that they contain.

There was a distinct bureaucratic difference between what were understood to be the monarch’s public papers, particularly those that were created by the more ancient offices of government such as the Chancery, Exchequer, or the common law courts, and those within the State Papers Office. The former, which emerged as part of the ordinary business of government, such as the collection of taxes or the administration of the state, were stored at the Tower of London, Westminster Abbey, and the Rolls Chapel, accumulating from the twelfth century onwards.

What we now understand as State Papers were considered the private business of the monarch and were retained by the keepers at Whitehall. This was not just an informal understanding; the early keepers of the State Papers swore as part of their oath of office to ensure that only authorised persons were to look at the king’s papers having secured the permission of the lord chamberlain.

One benefit of the State Papers is that they allow us to see the inner workings of government as officials developed policies and legislation, considered proposals at council, or responded to major and minor events. Prior to the sixteenth century, we have only snippets of similar material, but from Henry VIII’s reign onwards, during the administrations overseen by Cardinal Thomas Wolsey and his successor, Thomas Cromwell, we can bear witness to the private and public opinions of senior officials through their correspondence.

Seals of Office

When trying to understand the State Papers, it is helpful to think about where they came from. Before the sixteenth century, no such collections as those we now call State Papers existed, as the office was not created until the 1530s. There were, of course, officials who managed the crown’s business prior to the sixteenth century, centred on the medieval chancery and embodied by those who held the principal royal seals.

The Great Seal of England was the principal seal and was held by the lord chancellor of England. It acted as the final device used to authenticate outgoing business when a wax impression of the seal was affixed to documents. Instructions within the documents were only acted upon when the seal was affixed, signifying the crown’s preference.

Next in seniority came the Privy Seal. From the fourteenth century onwards, most government work originated with the Privy Seal Office, from where orders were issued to other departments, especially the chancery, to act on the monarch’s instructions.

The third and final seal to emerge was the Signet. Although it came into existence late in the fourteenth century during Richard II’s reign, it garnered an increased authority from the sixteenth century when it came into the possession of the newly created office of secretary of state, empowering the holder to act upon the monarch’s instructions by issuing orders across government.

Each of the seals should be understood as acting independently of each other to ensure the smooth functioning of government in London. Their use also reflects the chain of command where the monarch instructed his secretary of state to use the signet to send warrants [orders] to the lord privy seal, who then instructed the relevant government department or office to act on the monarch’s instructions by using the privy seal, and when completed or implemented, the outcome was announced under the authority of the great seal, often through a letter patent or letter close.

From Henry VIII’s reign onwards, the secretary of state made increasing use of the signet as he managed an expanding portfolio of royal business although the archaic use of the signet lessened, to be replaced with letters signed by the secretary and his officials on behalf of the monarch. This reflected the shift in government, where the large, formal documents that were issued by the crown still bore the Great Seal, but the day-to-day government of England and its territories shifted to the secretary of state.

Origins of the Secretary of State

The first person to fulfil the role of secretary of state in England was Thomas Cromwell, who served Henry VIII, although he and his immediate successors were known as chief or principal secretary (Thomas Cromwell himself was often referred to as “Master Secretary”). While Cromwell did not survive Henry’s reign, the role did, and as the sixteenth century developed, the office became known as that of the Secretary of State. This was further consolidated when the responsibilities of the office were formalised and divided between two secretaries as the volume of work increased. The novelty of the office (in comparison with more ancient positions of government) meant that its remit and functions were ill-defined and often depended on the power and influence of the holder as well as their personal relationship with the monarch.

Modern understanding of their functions is also partly dependent on the survival of letters, such as Thomas Cromwell’s, which were confiscated when he was arrested on charges of treason in 1540, although it is also likely that most copies of his outgoing letters were intentionally destroyed by his staff when he was arrested. What was confiscated were held at the Treasury of the Exchequer at Whitehall until the mid-nineteenth century, when they were transferred to the modern State Papers Office, and then incorporated into the Public Records Office and now form the basis of our understanding of Henrician England. Their confiscation and modern classification in SP 1 can be contrasted with the much smaller collection of papers from Cromwell’s predecessor, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey.

Exemplified by Thomas Cromwell, and emulated by many of his successors, the secretary of state was one of the most powerful officials at court, spending considerable amounts of time with the monarch, acting as their private secretary, managing privy council business, and issuing instructions across government. The office, though, was so burdensome, that occupiers struggled to manage the workload for long before either falling out of favour or succeeding to higher, but less onerous, positions. The role of secretary of state can be understood as a clearing house, where most of the correspondence for the monarch’s attention was addressed to them, or their staff, on the understanding that the matter will be discussed with the monarch

Keepers of the Records

As the sixteenth century progressed, an increasingly large body of paperwork began to accumulate in the Secretary of State’s office, which needed to be sorted and stored. Perhaps it is best to think of the early years of the State Papers Office as an extension of the Secretary of State’s office before emerging as a distinct part of government in its own right as the first officials who were given responsibility for sorting and storing the paperwork were already closely associated with the internal workings of the Secretary of State’s office.

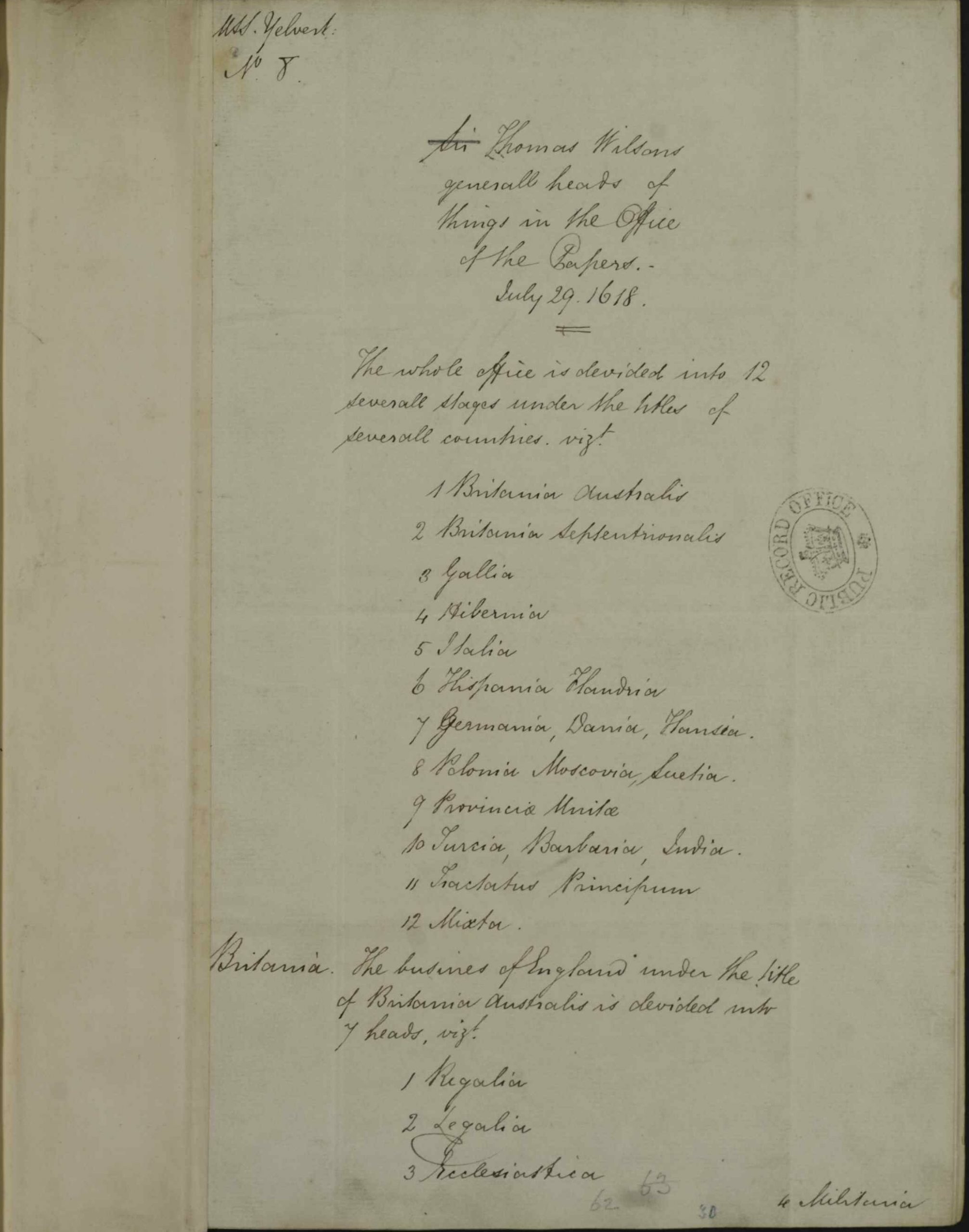

Initial attempts were made during Elizabeth I’s reign to place some order on the increasing volume of letters, papers, and correspondence that was pouring into London. Thomas Wilson was appointed a member of Elizabeth’s privy council and Secretary of State in November 1577, but he may have already been informally sorting the accumulated papers. A patent was issued in 1578 announcing the appointment of a ‘clerk of the papers’. While the recipient is unknown it is reasonable to assume it was granted to Wilson. Whether or not he had an immediate successor remains unclear, as he died in 1581 and the role may have fallen into abeyance until Sir Thomas Lake was formally granted a £30 salary in 1603 for ‘keeping, airing and digesting’ the king’s papers, work he had likely undertaken since (at least) 1597. Lake surrendered his keepership in early 1610 to two men, Sir Thomas Wilson and Levinus Munck, although Munck had little interest in the role and was succeeded by Ambrose Randolph in 1614.

Over the next decade, Wilson and Randolph transformed the office. They were bolstered by securing rooms in Whitehall palace to store the papers in chests, but this was soon upgraded to bigger rooms with bays, where the papers were sorted into specific topics. The first papers received into the keeper’s office were not Thomas Cromwell’s as these papers remained in the Treasury of the Exchequer. Instead, it appears that Thomas Wilson was gathering items mainly of diplomatic papers and ambassadorial reports from English embassies abroad.

Sir Joseph Williamson

A critical element of this expansion was the work of Sir Joseph Williamson. He served as under-secretary of state between 1661 and 1674, when he was promoted to secretary of state and sworn to the English privy council, which he served on until 1679. Williamson was the leading member of a new generation of administrators, and while not a first rank politician such as Henry Bennet, earl of Arlington, who served as Charles II’s secretary of state between 1662–1674, Williamson’s skills lay in the efficient running of the secretary of state’s office, the gathering of information, and a clear eye for detail. Far more effective as a bureaucrat then as a politician, Williamson became a trusted figure in Charles II’s Restoration government. Williamson was a prolific correspondent, creating a large network of informers and officials, who fed him a regular stream of news, even when there was little to report and Williamson was seemingly undaunted by the volume of material that needed to be processed. Crucially, alongside his duties as under-secretary, Williamson was also appointed keeper of the State Papers Office on 31 December 1661, a role he retained until his death in 1701. During the four decades in post, he created a vast archive.

His dual role in both the secretary of state’s office and as keeper of state papers is keenly relevant, as we can track the transfer of records to the State Papers Office. Although he very much prioritised his role as under-secretary and then secretary of state, he appears to have been diligent in ensuring the smooth transfer of large amounts of materials into the State Papers Office. After his death, a survey was undertaken of the keeper’s offices and it was found to be in relative disorder, with the papers poorly stored, and a parliamentary commission was left to try to make sense of what had been gathered.

Assembling the State Papers Ireland

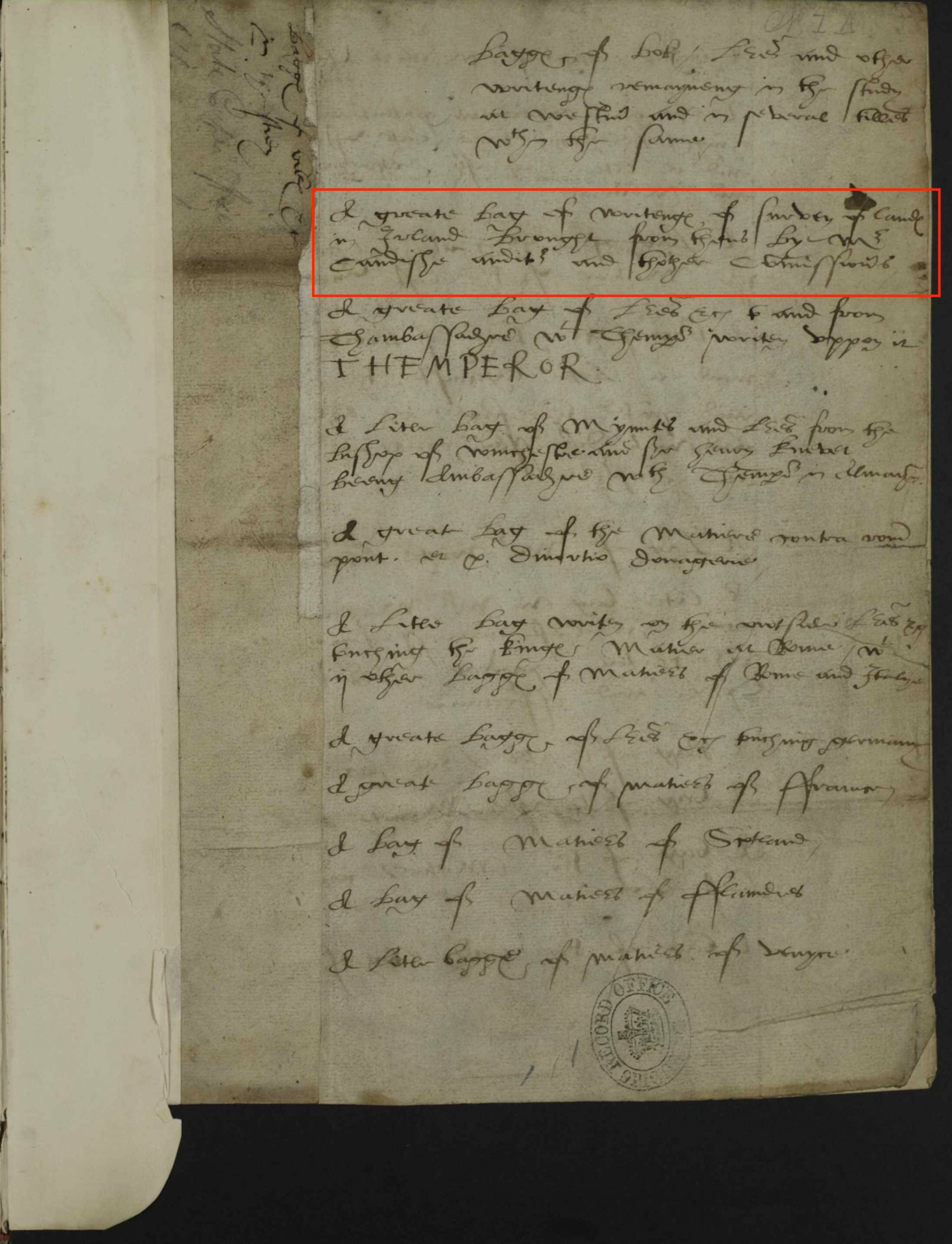

Soon after the establishment of the State Papers Office in 1578, the keepers sought the transfer of material from the Secretary of State’s office. The initial deposits were diplomatic in nature and focussed mainly on reports sent from ambassadors. There was only a small number of domestic materials as the senior officials from across government were reticent to relinquish records created during their tenure. From the very beginning, however, Irish records formed part of these transfers. In what might be a list of the very first documents transferred to the State Papers Office, a list entitled a “Bagge of Bokes, L[ett]res and other writings remayneng in the study at W[est]m[i]nster and in the several tilles within the same”, notes that “A greate bag of writinge[s] of survey of lands in Irland brought from there by Mr Candishe [Cavendish and th[e]other Commissioners”. It is likely written in Sir Ralph Sadler’s hand, who served as secretary to Thomas Cromwell before assuming the office of chief secretary in 1540 and the records likely date from Edward VI’s reign.

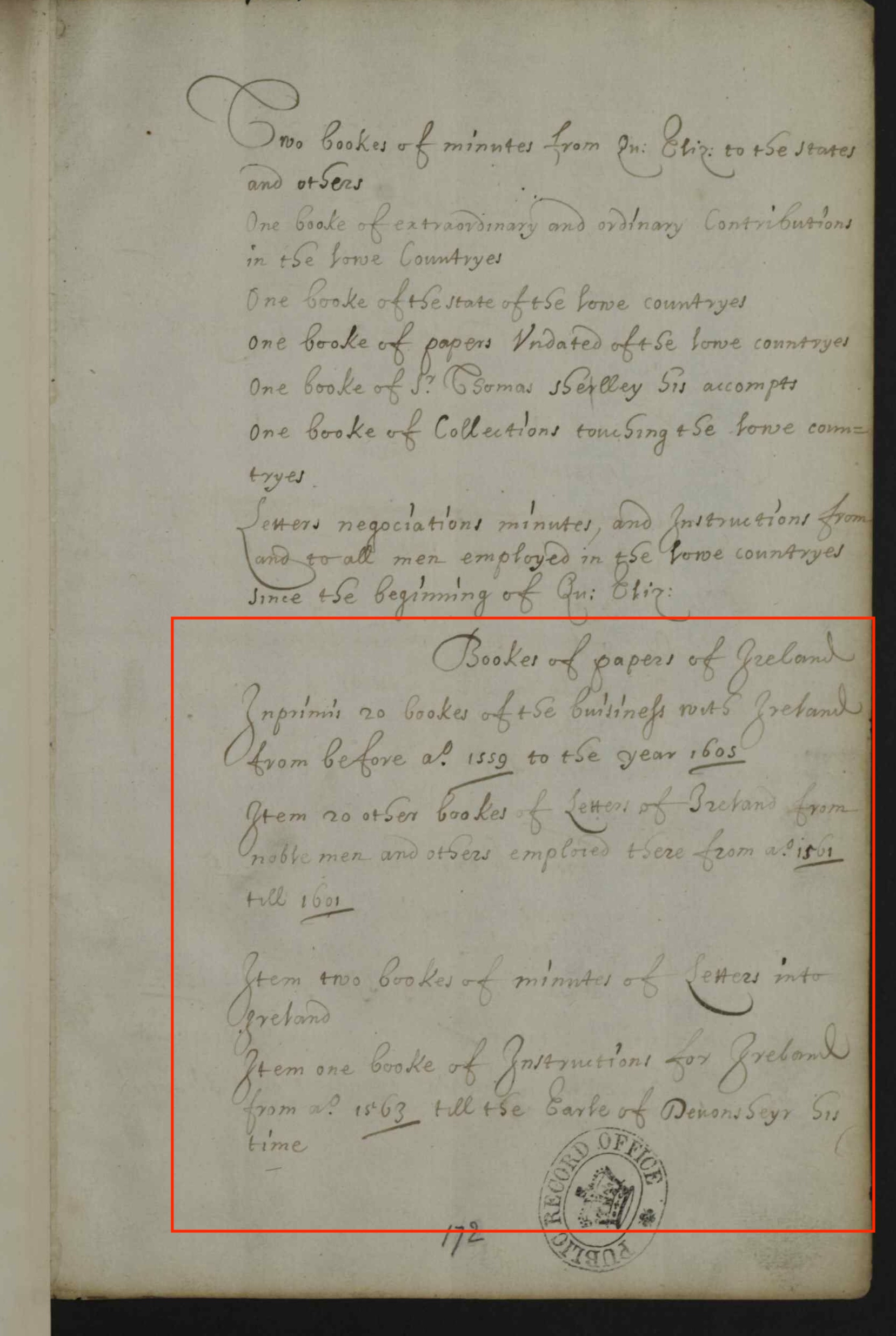

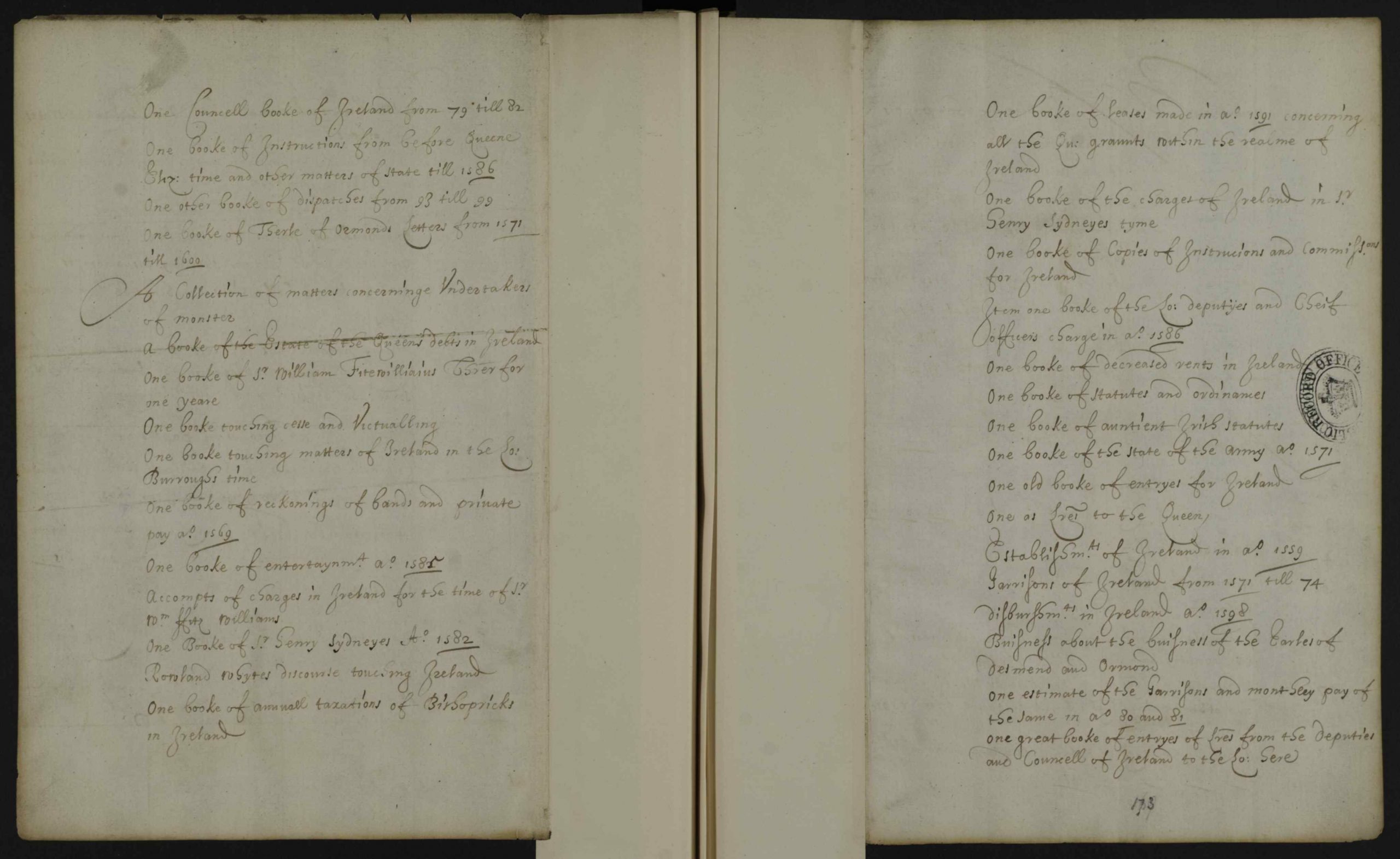

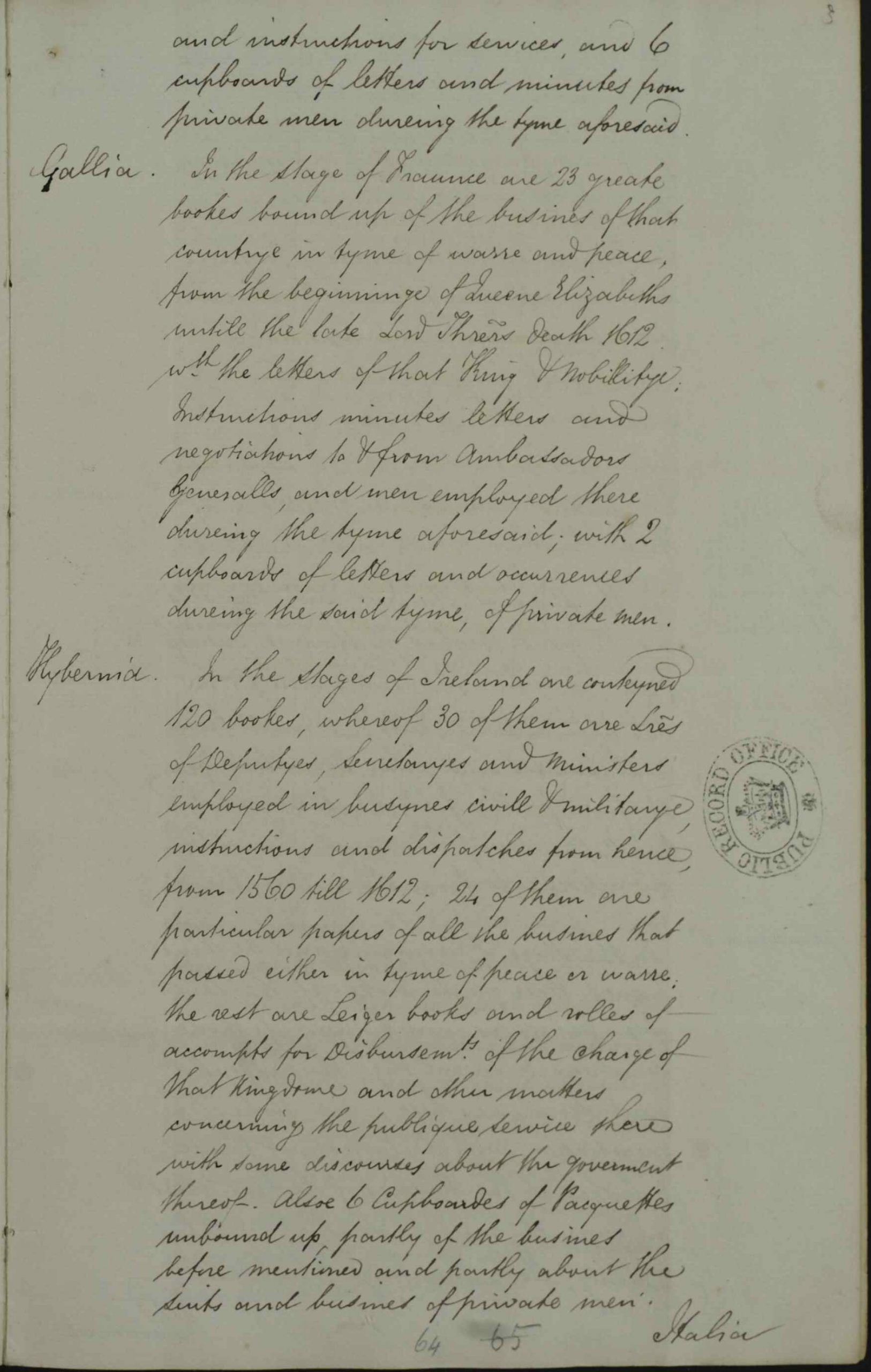

There are two specific volumes of records that provide insights into the workings of the State Paper Office (SP 45/20 and SP 45/21) and in a majority of the lists that records the transfer of documents to the State Paper Office, material related to Ireland can be seen. By 1612-13, Thomas Wilson noted that beyond domestic material related to England, Irish papers outnumbered every other country [SP 45/20, f. 33v]. James I seems to have agreed, as on a visit to the State Papers Office in 1618, the king is alleged to have commented “that we had more adooe wth Ireland than with all the world besydes”. [SP 14/107, f. 24] By this point, Wilson had created a sub-division specifically for Irish records, alongside the other areas of the growing collection.

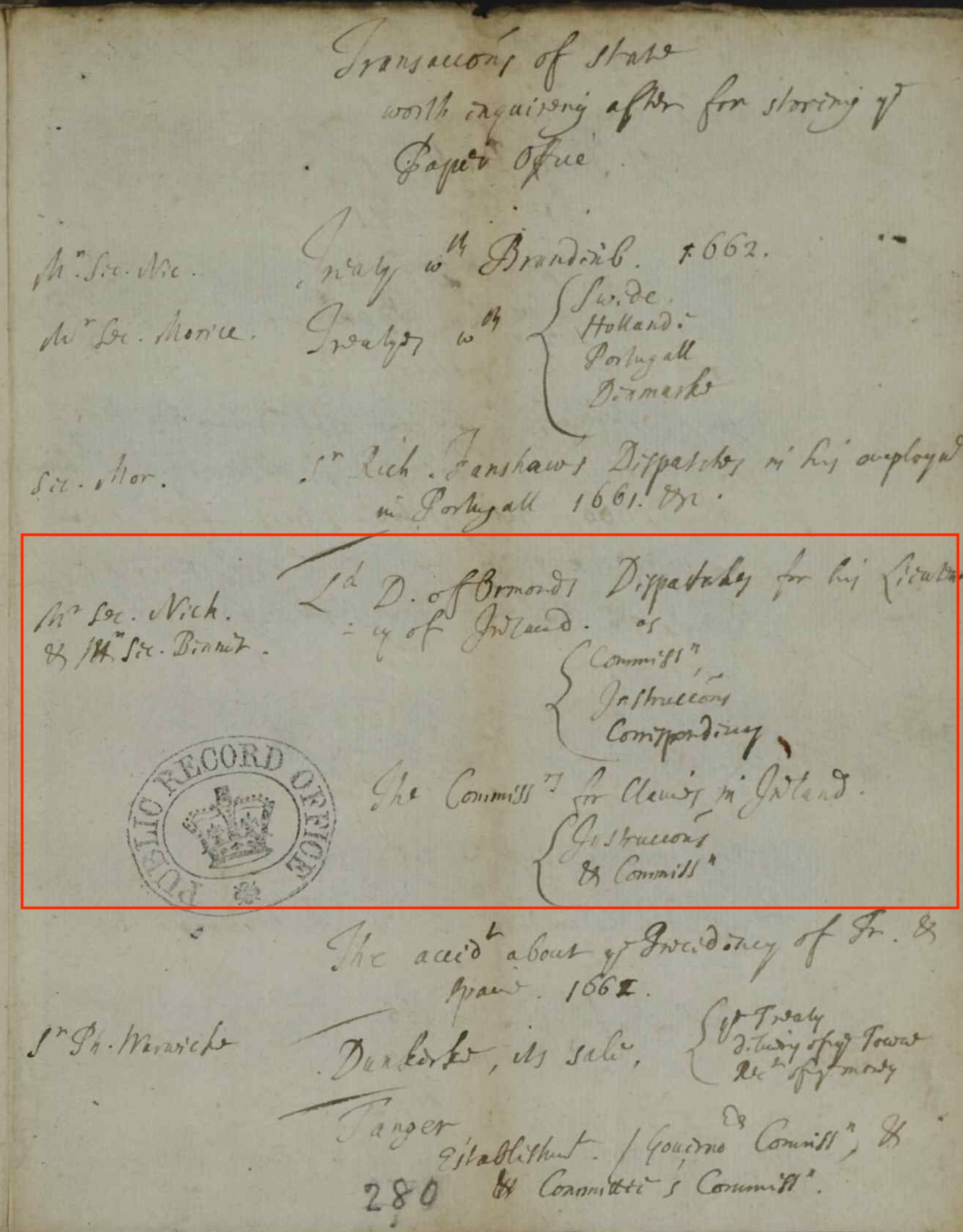

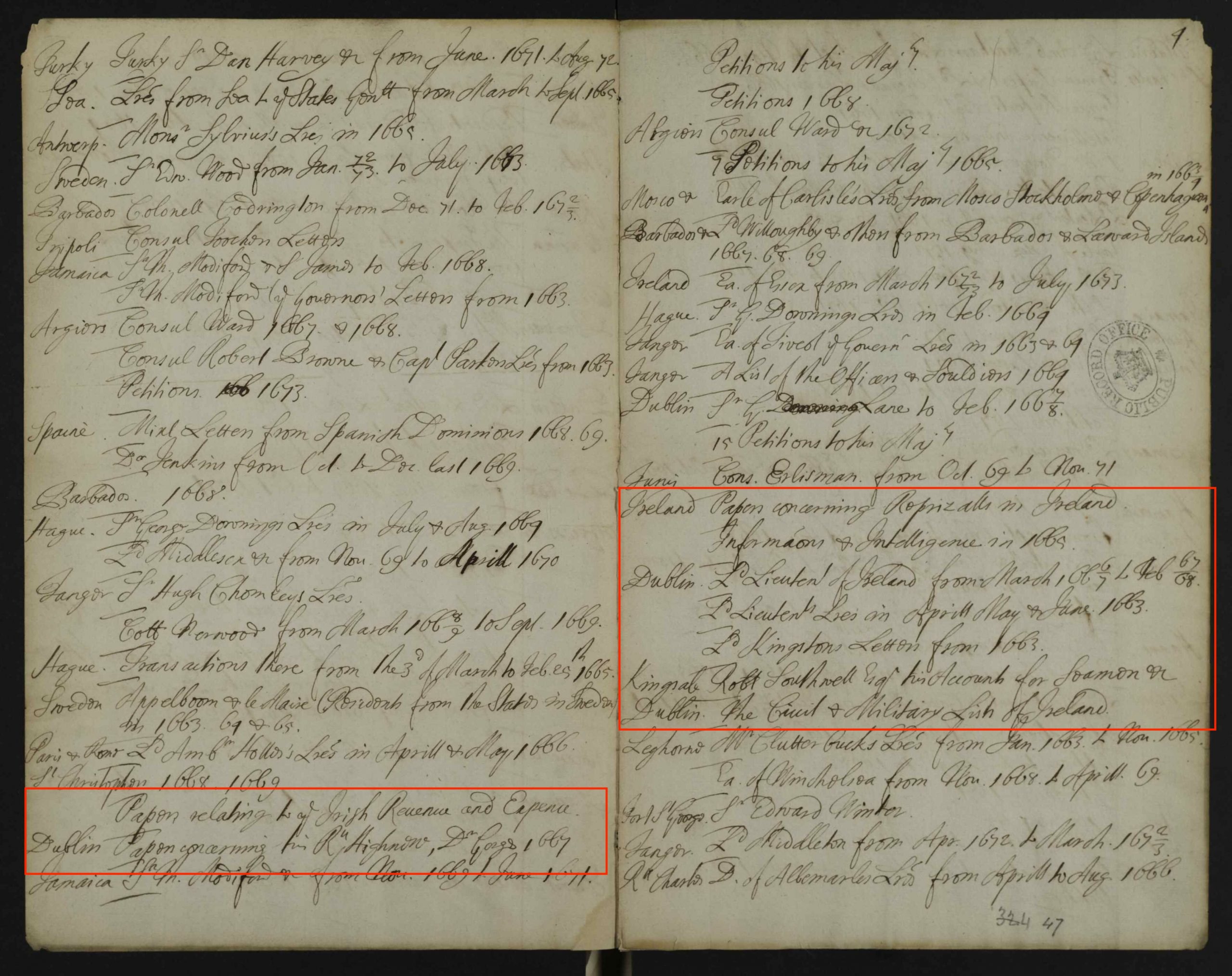

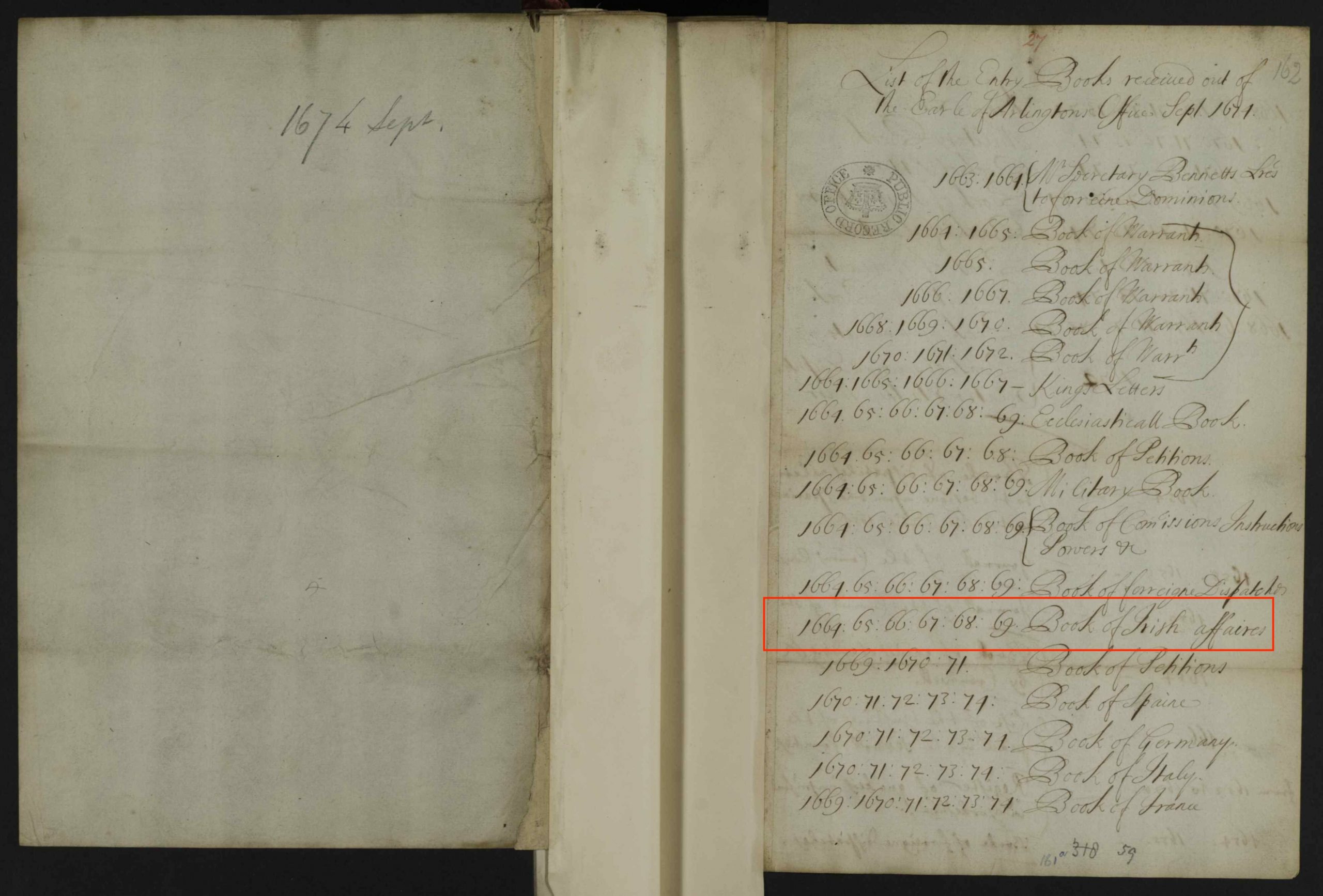

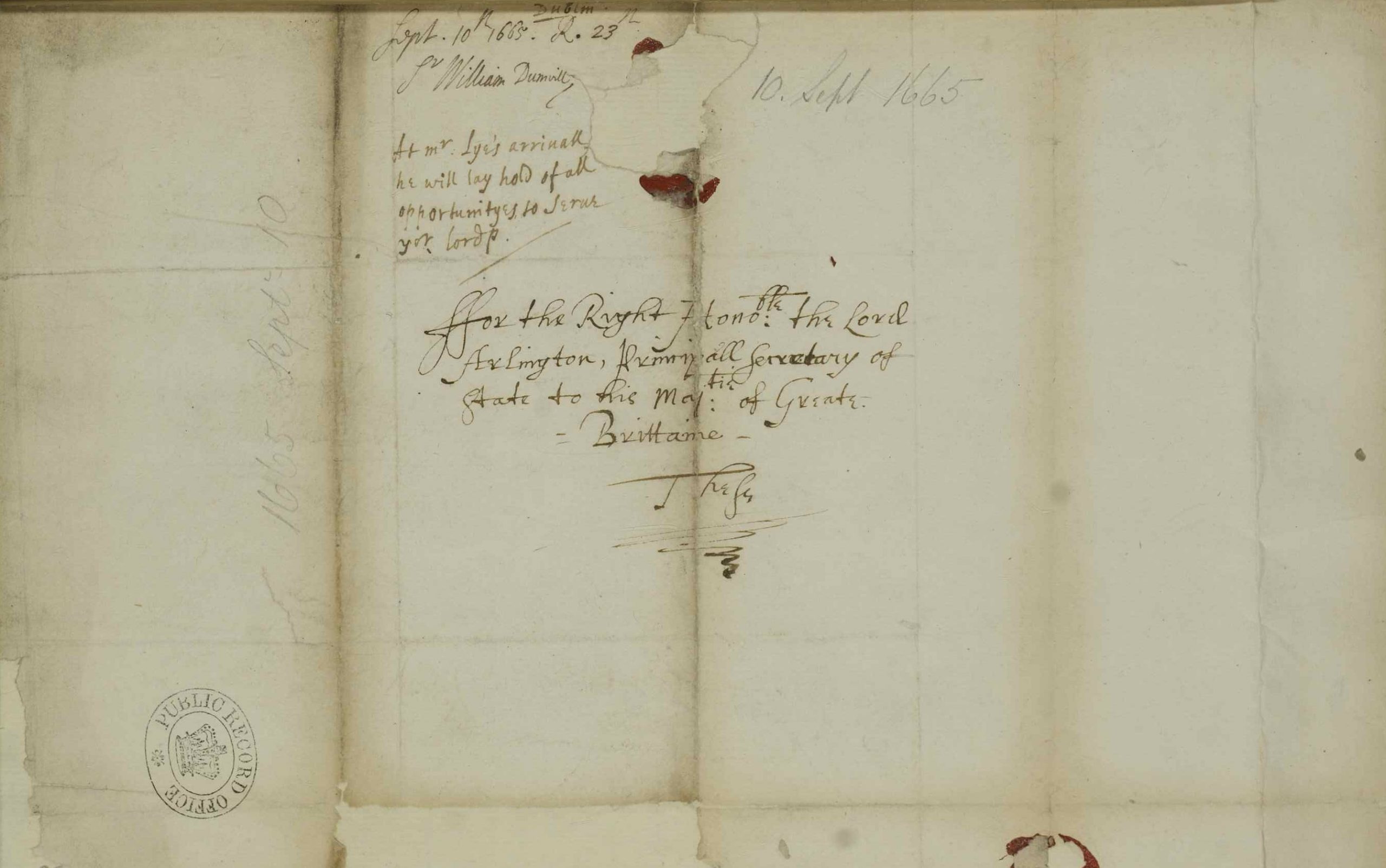

In the coming decades, the quantity of papers about Ireland only increased. By the early 1660s, we can see Joseph Williamson’s work in transferring bundles of letters to the State Papers Office. There are numerous lists of sorted letters that were moved into storage and are likely the same letters that were bound into volumes in the nineteenth century and are now on the Virtual Record Treasury of Ireland.

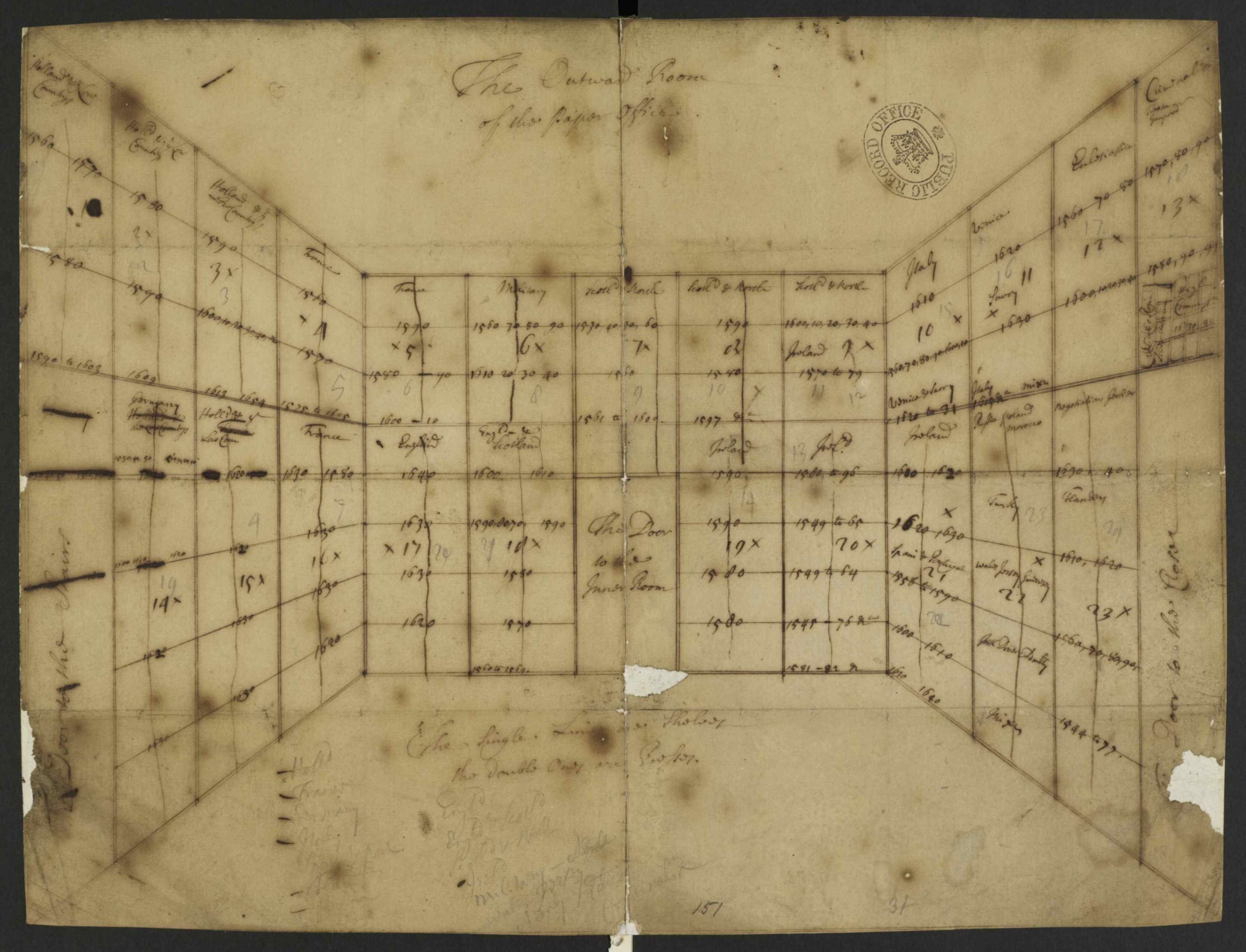

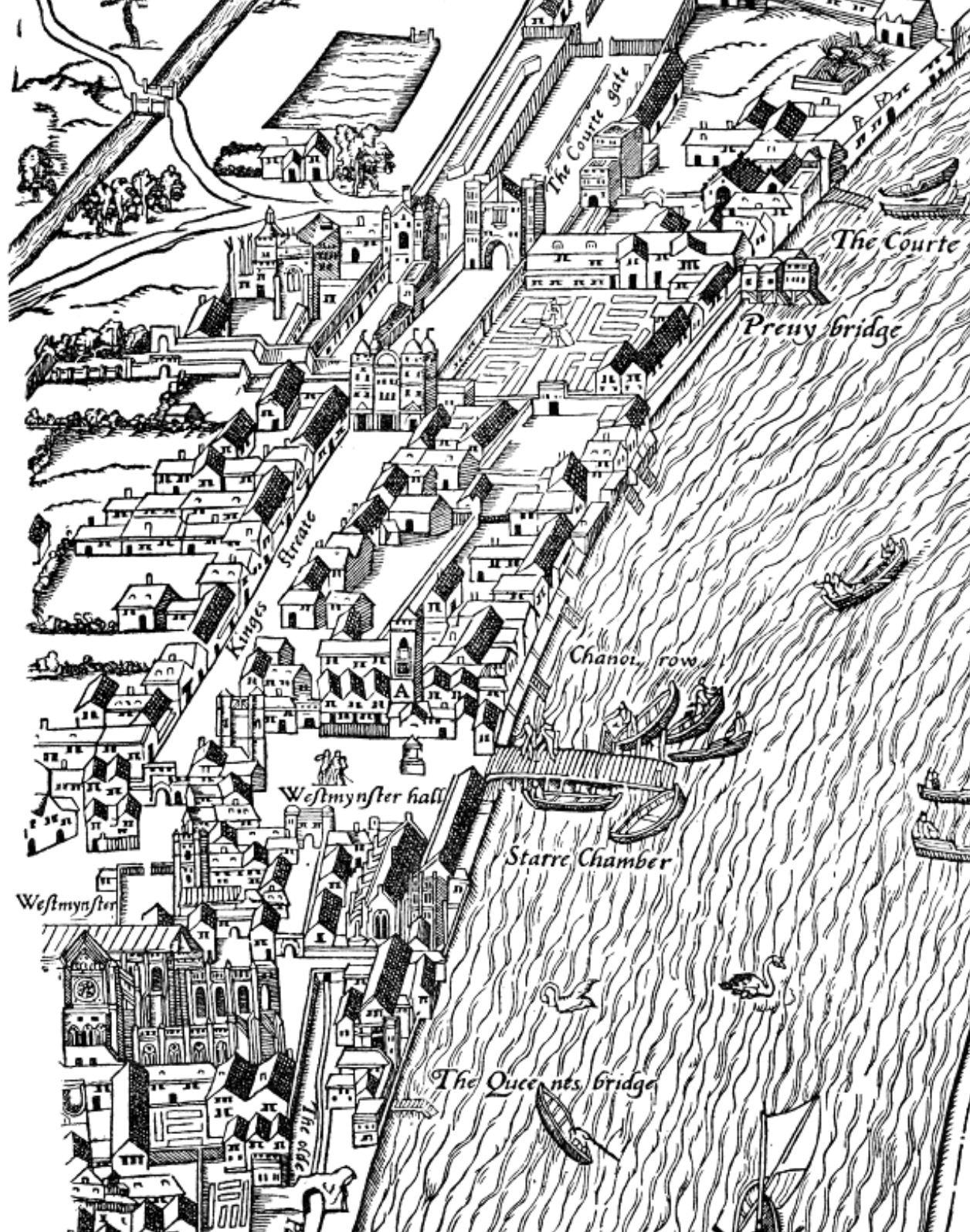

We can also see how the materials were stored in the State Papers Office. These drawings, dated 1682, shows how the Irish material were gathered together (to the right of the door in this image)

There are two specific volumes of records that provide insights into the workings of the State Paper Office (SP 45/20 and SP 45/21) and in a majority of the lists that records the transfer of documents to the State Paper Office, material related to Ireland can be seen. By 1612-13, Thomas Wilson noted that beyond domestic material related to England, Irish papers outnumbered every other country [SP 45/20, f. 33v]. James I seems to have agreed, as on a visit to the State Papers Office in 1618, the king is alleged to have commented “that we had more adooe wth Ireland than with all the world besydes”. [SP 14/107, f. 24] By this point, Wilson had created a sub-division specifically for Irish records, alongside the other areas of the growing collection.

In the coming decades, the quantity of papers about Ireland only increased. By the early 1660s, we can see Joseph Williamson’s work in transferring bundles of letters to the State Papers Office. There are numerous lists of sorted letters that were moved into storage and are likely the same letters that were bound into volumes in the nineteenth century and are now on the Virtual Record Treasury of Ireland.

We can also see how the materials were stored in the State Papers Office. These drawings, dated 1682, shows how the Irish material were gathered together (to the right of the door in this image)