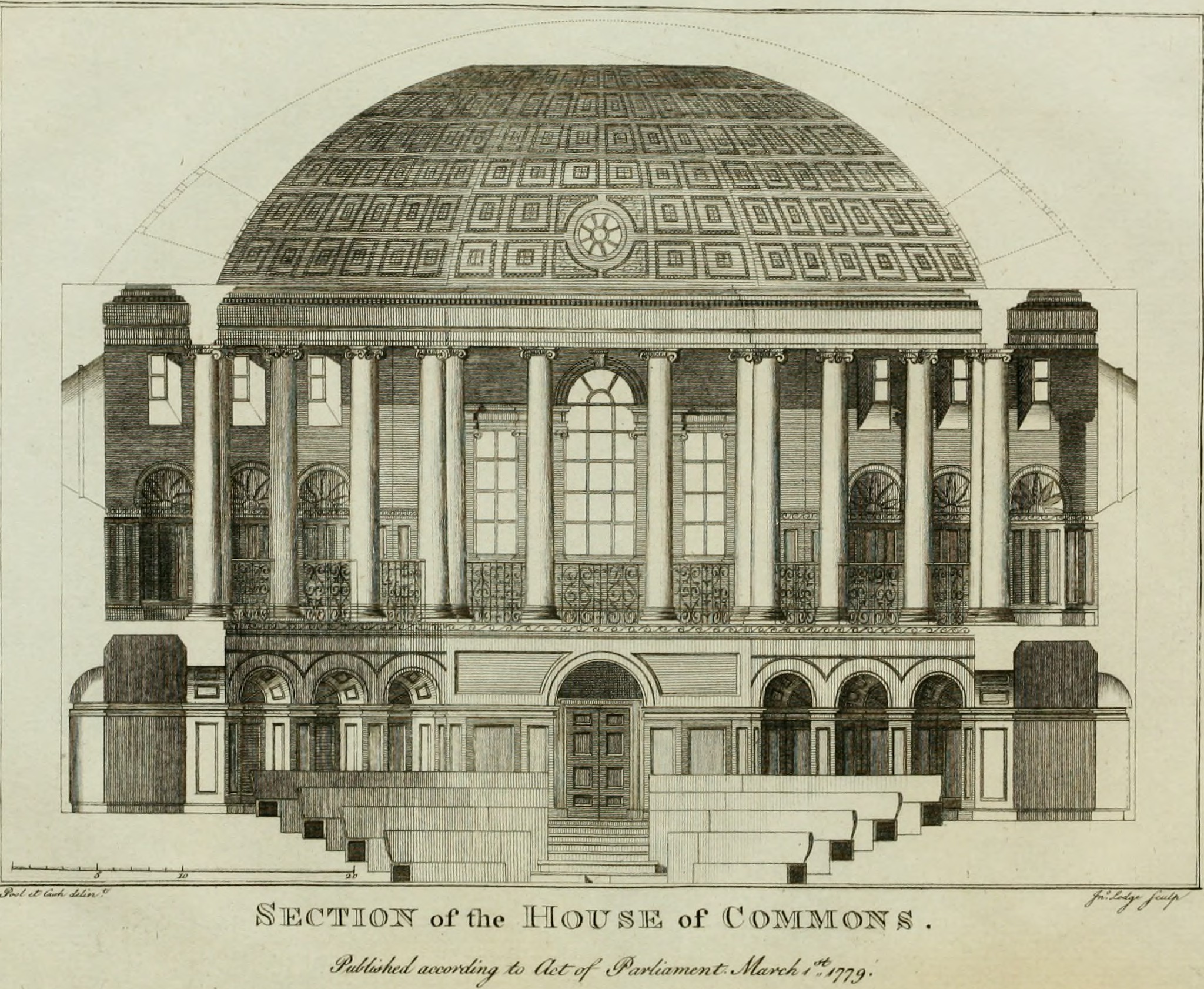

The Irish House of Commons, 1776–1801

Delving Deeper

The Irish House of Commons recovers the debates of the institution at the centre of legislation and law-making in Ireland before Union. The vast majority of the records of the Irish Parliament were destroyed in the fire that engulfed the Four Courts in 1922, but the debates have been painstakingly recreated here on the VRTI. In this delving deeper page you will find additional historical context on the Irish Parliament in the eighteenth-century, the archival history of the sources used to recover parliamentary debates, and an explanation of how these sources can be exploited to better understand the features and developments of late eighteenth-century Ireland and an Age of Revolutions.

Cite This Essay: Joel Herman, ‘The Irish House of Commons, 1776-1801 — Delving Deeper’ (VRTI 2025).

Historical Background

Historians have vigorously debated whether Eighteenth-Century Ireland was a kingdom or a colony, but there is a good argument that it was both of these things. The settlement that followed the defeat of the Catholic King James by the Protestant William of Orange in 1691 gave a Protestant minority the key to the ‘Kingdom of Ireland’. The Irish Parliament was the institution that not only assured the status of Protestants, of the established church, as the ‘political nation’, but also their firm grip on power and the ability to craft their own laws with some strings attached.

At the end of the seventeenth and beginning of the eighteenth century this political nation passed a number of ‘penal laws’ designed to exclude the vast majority of the population from political life and property. To describe the conditions of rule this Catholic ‘nation’ was forced to live under as colonial is not to stretch the definition of that term. On the other hand a Presbyterian community, about ten percent of the population, was caught somewhere in between. Protestant but with a well-known temper and tendency to cause those in power problems, Presbyterians were also kept from politics by a code of law not dissimilar to, but also not as severe as, the one enacted to control the Catholic majority.

From the viewpoint of each of these communities political rule looked a very different thing, but for all of them the Irish Parliament was central to their having a share in it. A birth right for some an aspiration for others, it was the ability to vote for, and sit in, parliament, and particularly the House of Commons, that represented the reality or hope of having a voice in the political process.

Modelled on the English/British Parliament, the Irish Parliament closely followed the procedures and precedents that had been established in that body, or at least as closely as those serving in it could. A number factors did force the Irish Parliament to function in slightly different ways. One of these factors was the presence of mechanisms by which the English government continued to exert its authority over Ireland. Poynings’ Law of 1494 is the most important of these mechanisms to point out. A subject that has taken up a lot of ink, Poynings’ Law meant different things at different times. At first used to control the Irish Parliament in a number of different ways, in the aftermath of the Glorious Revolution it came to mean something different.

As the British Parliament set out the misdeeds of James and asserted its rights in offering the throne to William and Mary in the ‘Declaration of Right’ in 1689, members of the Irish Parliament sought to establish the rights of the Irish Parliament in the 1690s. This led to the reshaping of procedure under Poynings’ Law and debates over whether the British Parliament could legislate for, or ‘bind’, the Irish Parliament – a question that was ultimately answered by the other major curtailment of Irish Parliamentary right that needs mentioning. The Declaratory of Act of 1720 made exactly this claim: ‘the King’s majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the lords spiritual and temporal and commons of Great Britain in parliament assembled, had, hath and of right ought to have full power and authority to make laws and statutes of sufficient force and validity, to bind the kingdom and people of Ireland’.

However, the bark was worse than the bite as this ‘right’ was rarely used and it was instead Poynings’ Law that continued to limit the powers of the Irish Parliament, but now in a lesser way than it originally had. In the most basic terms, the legislation proposed and drafted in the Irish Parliament, called ‘heads of bills’, had to be approved by certain bodies within the British government in Ireland and London before it could be passed into law by the Irish Parliament. The most important of these bodies was the English Privy Council, which often exercised its right to kill or amend ‘heads of bills’ before sending them back to the Irish Parliament. It was then up to Irish members of Parliament, or MPs, whether to accept these changes and vote the bill in, or reject them by voting against it.

This was the process followed throughout the eighteenth century, although at the start of each session there was a certain order to proceedings as well as further procedural steps to follow for different types and kinds of legislation. For example, the bills used to raise money for the government, and the British military garrisoned in Ireland, were highest on the priority list of Dublin Castle, which was occupied by Lord Lieutenant and the British executive in Ireland. The passage of these ‘Money Bills’ was central to each session of Parliament, and especially the House of Commons where the bills originated.

Resistance to the government’s favoured terms became a tool that could be used by those sitting in opposition to push their own programme of legislation, or against other legislation planned by the British executive in the session. Opposition became a greater possibility in the second half of the century when the pace of politics was increased by the introduction of parliamentary terms in the Irish House of Commons. Before this point the duration of Parliament’s had been for the entire rule and reign of a sitting monarch. As a result, elections were incredibly infrequent for the first half of the century, occurring only a few times.

It was the Octennial Act of 1768 that divorced the Irish Parliamentary calendar from a royal one and brought about an election just several years after the succession of George III in 1761. Although parliamentary sessions continued to take place every second year until 1783, when Parliament began to meet annually, elections now occurred every eight years. This dovetailed with the emergence of other features such as a more vocal press, the printing of parliamentary debate, the interventionist policy of the Castle, and developments in London, Britain, and the wider British Empire to fundamentally change the rhythm of Irish politics in the late eighteenth century.

Late Eighteenth-Century Developments

The story of the eighteenth-century Irish Parliament – a snapshot of which is offered above – has been likened to a period of ‘long apprenticeship’, in reference to the ways in which the Irish legislature was modelled after the British one in structure and practice. In 1782 this apprenticeship came to an end with the arrival of ‘Legislative Independence’, and the removal of those mechanisms designed to limit the legislative powers of the Irish Parliament.

This period of ‘Legislative Independence’ was short-lived, as ‘The Acts of Union’ of 1800 abolished the Irish Parliament less than twenty years after it had begun. The debates found in this gold seam, and particularly the ‘curated debates’, reveal the reasons why this new experiment in shared rule faltered rather quickly. Three of these loom large: the increasingly volatile constitutional relationship between Ireland and Britain, unreformed mechanisms of colonial rule including parliament itself, and the demographic and increasingly sectarian realities of the island – all of which had contributed to the rebellion of the United Irishmen in 1798.

As has been noted, conflict between the British and Irish Parliaments stretched further back in time. However, it was in the second half of the eighteenth century that a series of controversies opened up the question of serious constitutional change, concessions were eventually forced by a popular movement in Ireland, and the likelihood of a legislative union increased, as British politicians gradually became convinced that it was the only way Ireland could be managed.

This change finally came during an imperial crisis that emerged in the British Empire in the 1760s and escalated into an imperial civil war in the 1770s. Trying desperately to win this war against the former ‘American colonies’, and now ‘United States’ and their allies, British ministers were operating from a place of weakness when things kicked off in Ireland. In 1779, roughly three years after the Declaration of Independence had been ratified by the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, and the American War of Independence had begun, a patriot movement, directed from the House of Commons by Henry Grattan and Henry Flood, and other patriot MPs, and represented by an armed militia, known as the Volunteers, forced significant commercial concessions from the British Parliament. The agitation for ‘Free Trade’ was followed by campaigns for further political concessions and for a ‘Declaration’ of the rights of the Irish Parliament.

In April 1782, this ‘Declaration of Right’ was passed in the House of Commons and Legislative Independence followed shortly thereafter. The strictures that had constrained the full legislative powers of the Irish Parliament were now lifted. The Irish Declaratory Act of 1720 was repealed by the British Parliament that summer, and in ‘The Irish Appeals Act of 1783’ British ministers went even further by acknowledging the ‘right’ of the people of Ireland ‘to be bound only by laws enacted by his Majesty and the Parliament of that Kingdom’.

The potential of this new found independence, was in fact rather limited. Although the Irish Parliament could now pass legislation unimpeded, the continued resistance of a narrow elite to parliamentary reform and emancipation eventually led Catholic and Presbyterian communities to rebel. It was this rebellion in 1798, along with the political manoeuvring and bribes of the British government, that convinced a sizeable enough majority within the Irish Parliament to give up their recently won independence, accept the union that was being offered, and in doing so, vote the Irish Parliament out of existence.

Unwilling to open its doors and benches to members of the different communities living on the island, the Protestant Ascendancy, as the elite would become known, surrendered the Irish House of Commons and with it local rule. In doing so, they changed the course of modern Irish history.

In Union the kingdom and the colony were subsumed and integrated more fully into the British imperial state and the Irish population became even more deeply entangled in the sinews of war and power of the empire. The debates in this period of ‘Grattan’s Parliament’, 1782-1801, are essential to understanding how an institution that was so fundamental to life on the island for hundreds of years could quite suddenly be extinguished, and the aftershocks, disappoints, and hopes this ending would continue to inspire in the future.

Reconstructing the Debates: Archival History and Recovery

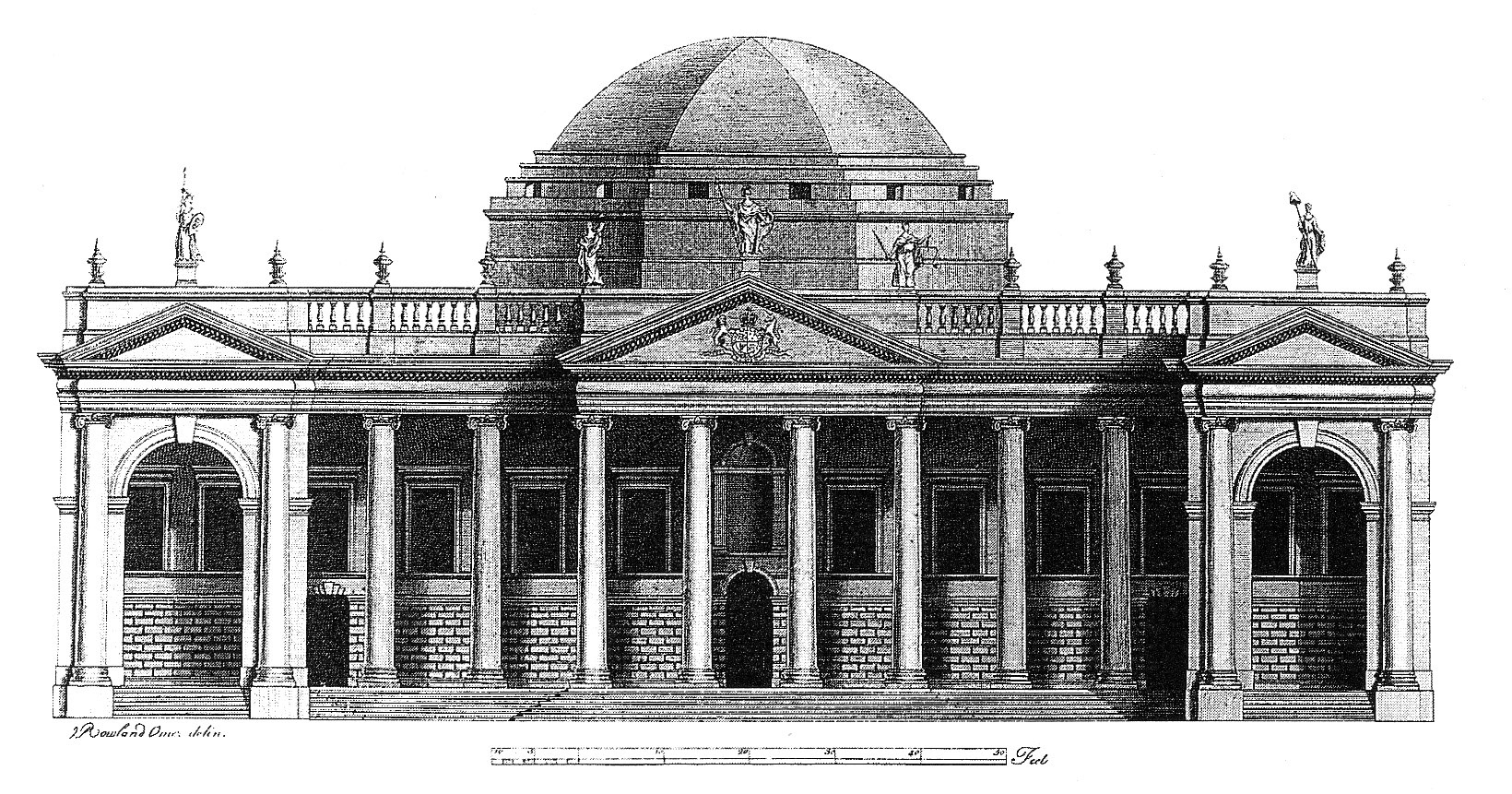

The end of the Irish Parliament also raised more practical concerns such as the removal of hundreds of years of records to make way for the bank that the parliament building was to become. These records were first carried by cart to a dilapidated house on Anglesea Street in 1802, but a good deal of lobbying eventually secured them a more permanent home and dedicated space in the Dublin Castle complex in 1812, although it wasn’t until 1815 that the transfer had been completed. Deputy-Keeper Theobald Richard O’Flaherty described the arrival of this Parliamentary Record Office with unreserved excitement:

The great national object has been attained of having the Parliamentary Records of Ireland deposited in a state completely calculated for future preservation; and that an easy and immediate access may be had to any record therein contained, on the most reasonable terms…

It was from this Parliamentary Record Office that they were moved to their final destination in the Public Record Office of Ireland (PROI) where so many of them would be destroyed in the fire of 1922.

The section of Herbert Wood’s famous Guide to the Records Deposited in the PROI, which outlines the contents of the earlier Parliamentary Record Office, makes for sobering reading, as it gives a better idea of what was lost in the fire – Bills, Returns, Law Papers, Petitions, Proclamations, Accounts, Statutes, Minute Books, Journals, and Speeches. When added up, the numbers given in the original catalogue of the Parliamentary Record Office come to almost 2,000 bundles and over 80,000 individual records. One small solace in the face of this staggering loss is the fact that the Journals of the Lords and Commons were printed in the second half of the eighteenth century.

These Journals, which provide a formal account of the proceedings of the two houses of the Irish Parliament, can be used as something of a blueprint for piecing back together and ordering the parliamentary materials that were destroyed, and also for thinking about how we might go about replacing them. Editions of the Journals are held in the Trinity College Dublin Library and the National Library of Ireland, however, the printed versions of the Journals leave out the debates through which laws were ultimately crafted and approved. The very life-blood of parliament, debates and speeches provide a more accurate account of the legislative process than the Journals, as they reveal the speech acts and agency of those that made the institution hum with life. This begs the question: can these debates be recovered?

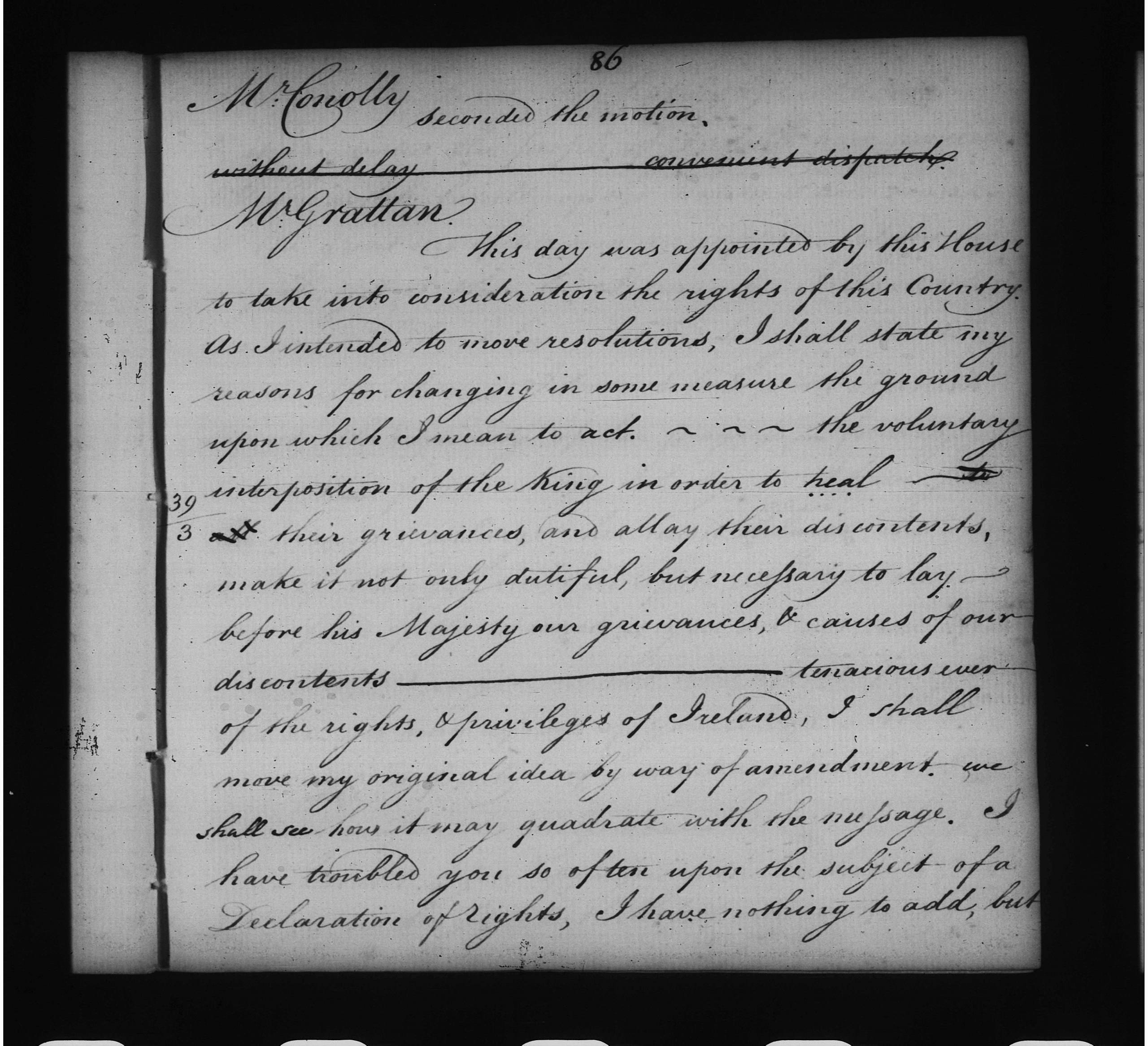

Sources such as the Parliamentary Register and reports carried by contemporary newspapers have been used to access the debates of the Irish Parliament in the past. But the acquisition of the ‘Cavendish Transcripts’ by the Virtual Record Treasury of Ireland (VRTI) has opened a new avenue for historical recovery. Transcriptions of notes taken by Sir Henry Cavendish in shorthand as he sat in sessions of the Irish House of Commons, the thirty-seven volumes of Transcripts run to over 10,000 pages. The circuitous route by which these volumes, and the original diaries of shorthand notes, came to occupy the Library of Congress in Washington, DC, has raised questions regarding authorship, and whether this was actually the work of parliamentary clerks. Whatever the case, it is the content of the collection that is of the greatest importance. Running through the years of the American War of Independence and to the outset of the French Revolution, the Cavendish Transcripts represent the sole surviving ‘record’ of the speeches of ‘Grattan’s Parliament’, opening a window into the law-making process itself.

But how does the content of the Cavendish Transcripts differ from the other sources we have for parliamentary debate? The Parliamentary Register, for example, was printed in 17 volumes, runs to over 7,000 pages, and offers more consistent coverage from 1781 until the Act of Union abolished the Irish Parliament, but when compared with key passages in the Cavendish Transcripts the Register loses out in detail. For example, Henry Grattan’s famous speech on 16 April 1782 calling for an Irish ‘Declaration of Right’ and Legislative Independence, which you can explore at greater depth in the ‘curated debates’ feature of this gold seam, is close to forty pages in the Transcripts and just six pages in the Register.

On the other hand, as noted above the printed Journals of the House of Commons give no record of parliamentary debate at all. Whereas newspapers, the other major source that can be consulted, are neither as detailed as the Transcripts nor as consistent as the Register. As a result of the limitation of these other sources, it is clear that the Cavendish Transcripts can offer greater insights into the legislative decisions that contributed to paths taken and not taken during an imperial civil war that divided old and new worlds. The Transcripts are particularly strong from 1777-1785 when coverage begins to breakdown, and it is from this point that the Register grows in importance until it leaves off in 1797.

‘The Irish House of Commons’ gold seam brings together both of these major sources, and a limited number of published debates on the Act of Union, to create the most comprehensive digital collection of Irish parliamentary debate from the build-up to Legislative Independence to the Act of Union. This collection will allow historians, researchers, students, and the general public, to reconsider political, cultural, religious, and economic developments in the late eighteenth century – developments which set the contours along which modern Ireland would take shape.

However, if the user is unfamiliar with the period and the developments described above it might still be difficult to find a way into these debates and the vast amount of material stored here. With nearly twenty thousand pages, and around 3 million words, of material at your fingertips it can be difficult to know where to begin, and this is why the ‘curated debates’ feature has been created.

The great national object has been attained of having the Parliamentary Records of Ireland deposited in a state completely calculated for future preservation; and that an easy and immediate access may be had to any record therein contained, on the most reasonable terms…

Curating the Debates

Designed to guide the beginner into the content of this gold seam, the ‘curated debates’ capture the major topics of parliamentary debate in the House of Commons in the late eighteenth century without sacrificing interpretive rigour. ‘Catholic Relief’, ‘Legislative Independence’, ‘Parliamentary Reform’, and ‘Union’. Four individual debates have been picked out and curated to draw out the fuller story of how these topics dominated the agenda of ‘Grattan’s Parliament’, and explain parliamentary procedure, the order of proceedings, how the outcomes and consequences of these debates impacted larger ongoing debates of which they formed a part, and point to other related debates and reading on each topic.

A short introductory essay accompanying each debate, offers this explanatory content and provides the reader with the baseline knowledge needed to engage with the text in an informed way. This text is arranged by speaker and follows the handwritten primary source closely, with some minor editorial interventions. Integrated into the VRTI data model and encoded in TEI, the ‘curated debates’ also allow easy navigation to the primary source – letting users jump directly from the text to the page being quoted in the Cavendish Transcripts or The Parliamentary Register. A host of relevant links to speakers in the VRTI Knowledge Graph and the Dictionary of Irish Biography provide additional background information, and at the end of each debate a list of related debates is given along with suggested reading.

The first ‘curated debate’, is on the topic of ‘Catholic relief’ and the initial attempt to alter the penal laws in a more serious way in the summer of 1778. Catholic Relief and debates on whether, and how, Catholics should be allowed into politics dominated parliamentary and public conversations in late eighteenth-century Ireland and led to the emergence of the Catholic question. The second ‘curated debate’ is on the topic ‘Legislative Independence’. Occurring on the 16 April 1782, it includes the passing of Henry Grattan’s ‘Declaration of Right’, which set out the conditions of Legislative Independence. Calls for ‘parliamentary reform’ followed quickly after, and this is the topic of the third curated debate. In March 1784 a number of petitions, setting out popular proposals for parliamentary reform, were debated in the House of Commons and rejected by a convincing majority.

The limited nature of parliamentary reform in the years that followed and the fact that Catholic emancipation was never fully granted, along with a number of other factors including the ferment of the French Revolution, ultimately resulted in the radicalisation of parts of the Presbyterian and Catholic communities, Rebellion in 1798, and Union not long after. The final ‘curated debate’ uses a printed report of the Union debates to recover this closing act of the Irish Parliament – an event that would put an end to debate in the Irish House of Commons for good.

Further debates could easily be added, but for now these four capture the most important themes discussed in the House of Commons, and function as a gateway into the collections made available in this gold seam.

Editorial Conventions

Minor editorial changes have been introduced to make the collections and curated features in this gold seam more accessible, especially to students and non-specialist.

First, the original titles found in the table of contents of the Cavendish Transcripts (LOC MSS27292 – Irish Parliament: House of Commons Debates, 1776-1789) have been enriched through the adoption of introductory keywords that come at the beginning of each title. Examples are provided below, along with an explanation of how these titles can be exploited. The meaning of each keyword is described in the Glossary of Terms at the end of this section.

Second, a number of small changes have been made to the texts of the curated debates (VRTI PARL/Debate – Irish House of Commons: Curated Debates). These debates are digital transcriptions of critical debates that appear in the collections of this gold seam. The changes are set out in full below.

1. Examples of Enriched Titles in the Cavendish Transcripts

Example 1:

Original Title: Alteration in the return for the Borough of Callan

Enriched Title: Debate: ‘Alteration in the return for the Borough of Callan’ (26 November 1777)

Explanation: In this first example ‘debate’ is the keyword and notifies the reader that a debate follows. The keyword, and the added date, make the search function much more powerful, as the reader can search the collection using the original title of the debate, the keyword, or the date.

Example 2:

Original Title: Mr Grattan perseveres in his motion

Enriched Title: Motion: ‘Mr Grattan perseveres in his motion’ (26 November 1777)

Explanation: In this second example ‘motion’ is the keyword and notifies the reader that a motion follows. Again, this also improves the search function as stated in the first example.

Example 3:

Original Title: Mr. Grattan introduces again his former motion

Enriched Title: Debate: ‘Mr. Grattan introduces again his former motion’ (1 December 1777)

Explanation: Here the original two points stand, but this example allows the demonstration of another important feature of the enriched titles. It is essential to note that in any case where a ‘motion’, or some other procedure, leads to an extended debate, the keyword ‘debate’ has been opted for as a general rule. In this example Grattan’s motion leads into a longer debate, so following the above stated rule the keyword ‘debate’ has been used rather than ‘motion’. This editorial decision is intended to guide the reader towards the most important part of these collections: the debates.

2. Curated Debates

The following slight changes have been made to the text of the curated debates, to improve the accessibility of this resource. The curated debates are broken down into sections and each of these sections is linked to the quoted source, so the reader can easily consult the original if needed.

Capitalization:

- In those instances where the first word of a sentence or phrase that comes after a full stop is not capitalized, the first word has been capitalized.

- All irregular capitalization in the original text has been retained.

Indentation:

- For longer speeches paragraph breaks have been introduced where appropriate.

Names of Speakers:

- Where the full name of the speaker is known I have included it. Where there is uncertainty due to multiple members of Parliament with the same last name, I have retained the title used for the speaker in the original text.

Spelling:

- Irregular spellings have been standardized. For example, ‘catholick’ has been rendered ‘catholic’; ‘publick’ has been rendered ‘public’; ‘intirely’ has been rendered ‘entirely’; ‘burthen’ has been rendered ‘burden’; ‘clamour’ has been rendered ‘clamor’, etc.

Other General Rules:

- Ampersands are written out as ‘and’.

- Irregular abbreviations are spelled out in full. For example ‘wd.’ will be rendered ‘would’; ‘thro’’ will be rendered as ‘through’; ‘look’d’ will be rendered as ‘looked’; ‘Hon.’ will be rendered ‘Honourable’; ‘rob’d’ will be rendered ‘robbed’; etc.

- Acts of Parliament have been standardized. For example, ‘the 2d of Queen Anne’ has been rendered as ‘2 Anne c. 6 [1704]’.

Glossary of Keywords:

Address – the house of commons issued an address in response to the address of the King and Lord Lieutenant that came at the beginning of each session of Parliament. An address could also be moved under different circumstances by a Member of Parliament (MP).

Attendance – the call of the house was a roll call of those present. Those that were not present were required to give an adequate excuse. The calling of the defaulters was a call a week or so later of those who were not in attendance and had not given an adequate excuse. Those who failed on both counts were to be taken into custody by the Sergeant of Arms.

Bill – to denote the reporting, printing, passage, or announcement of a bill. Also when an amendment or change is noted without debate.

Committee – committees were established for different purposes, the most common being a committee of the whole house, which presided over every public bill. For private bills smaller select committees were formed.

Complaint – complaints were made by members of the House of Commons for various reasons.

Debate – debate came at many different stages of the legislative process, but especially when motions were made and during readings of heads of bills and bills.

Election Committee – committees formed to consider petitions relating to elections.

Election Petition – petitions made to contest election results or protest against other aspects of elections.

Examination – the house called officers, government officials, and others for questioning relating to matters of importance.

Interruption – various interruptions occurred to the proceedings and debates of the House of Commons.

Item of Business – a general term used to describe procedures and proceedings for which the other keywords do not apply.

Message – messages were sent from the Crown or Lords to the commons.

Motion – an MP had to propose a motion to put forward a question, present a heads of bill, make an amendment, or resolution, and in a number of other cases. Motions had to be made, seconded, and read by the speaker, before the House was said ‘to be in possession of the question’. This is when the debate could begin.

Notice – an MP would commonly give notice that they planned to make a motion on a certain day.

Petition – petitions were made to call for bills or to protest against them, or the Acts that they would become.

Report – the whole house went into committee on public matters and legislation, but otherwise select committees dealt with private matters, the drafting of private legislation, elections, and other inquiries. These select committees would prepare a report for the house which could lead to legislation or other actions.

Speech – speeches occurred most frequently within debates, but in certain cases they are set apart from other proceedings.

Further Reading

Toby Barnard, ‘The Irish Parliament and Print, 1660-1782’, Parliamentary History, 33 (2014), pp. 97-113.

Bartlett, Thomas, The Fall and Rise of the Irish Nation: The Catholic Question 1690-1830 (Dublin, 1992).

David Hayton, The Irish Parliament in the Eighteenth Century: The Long Apprenticeship (Edinburgh, 2001).

Edith Mary Johnston-Liik, History of the Irish Parliament, 1692-1800 (6 vols, Belfast, 2002).

James Kelly, ‘Reporting the Irish Parliament: the Parliamentary Register’, Eighteenth-Century Ireland, 15 (2000), pp. 158-71.

Idem., ‘The Politics of the Protestant Ascendancy, 1730-1790’, in The Cambridge History of Ireland: Volume III, ed. by James Kelly (Cambridge, 2018).