Deeds of the Guild of St Anne, 1237 – 1778

Delving Deeper

This page provides descriptions of the documents in the Gold Seam, together with historical background and archival context. The information here is aimed at researchers who want to delve deeper into these fascinating collections.

Cite This Essay: Lynn Kilgallon and Theresa O’Byrne, ‘Deeds of the Guild of St Anne, 1237-1779 — Delving Deeper’ (VRTI, 2025).

Introduction

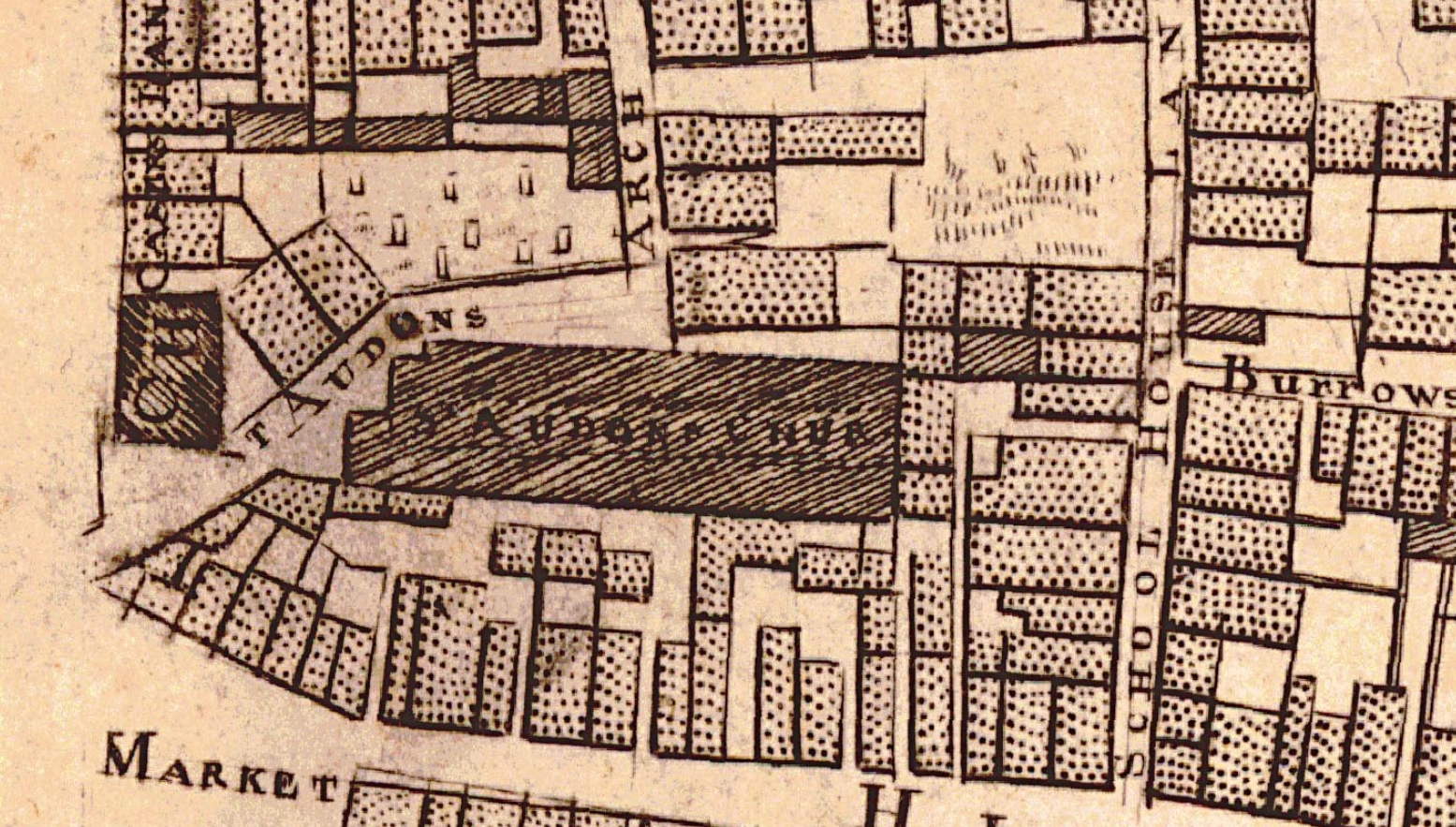

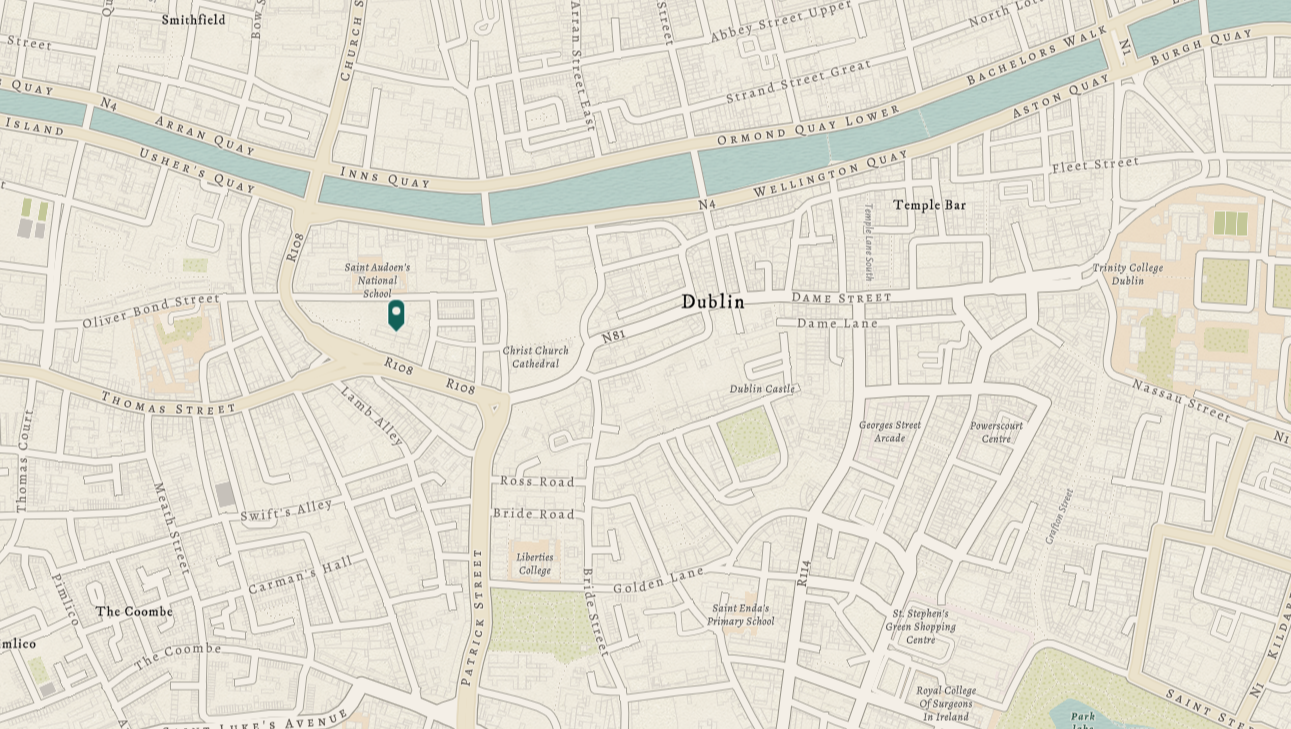

Founded in 1430 by royal charter of Henry VI (1422–1461), the Guild of St Anne was a lay religious organization that was formed to support the needs of six priests. The chantry chapel of St Anne’s Guild was in St Audoen’s church, Cornmarket, which is the now only remaining medieval parish church in Dublin. The church was located west of Christ Church cathedral, placing it just within western walls of medieval Dublin. It was at the heart of the medieval city.

The Guild’s members were made up of the men and women who lived and worked around St Audoen’s parish, Cornmarket, at the heart of the medieval city. Over the centuries, they produced many documents — deeds, or charters — recording information about their activities and interactions with the Guild. The parchment and paper deeds now held in the Library of the Royal Irish Academy (RIA) include approximately 718 documents ranging in date from 1237 to 1739. These are supplemented with approximately 175 further entries recorded in the Guild’s Abstract Book ranging in date from 1241 to 1796.

These records offer fresh insights into properties held by the Guild, including their buildings, owners, and renters. The deeds also include a number of wills, outcomes of cases at the Court of the King’s Bench in Ireland, and property exchanges enrolled by the Irish Chancery.

Economic information about housing and rental rates may also be extracted from wills and other property deeds. Information about buildings and infrastructure — types of material used, additions and removal, financing improvements, and intended use — can all be gleaned from this treasure trove; these are of particular interest to archaeologists.

Many early deeds name city officials, including the mayor, aldermen, city clerk, and others. The deeds also contain information about the families and properties of these officials and show how power and money were used in the medieval city. More precise mapping of medieval and early modern Dublin presents opportunities to study social history via the networks of friends, enemies, and neighbours recorded in the deeds.

Considerable information about women, families and familial relationships can also be traced through the deeds of St Anne’s Guild. These contain tantalising evidence for hidden histories, particularly about women and other individuals not commonly included in the historical record. Along with conveyances mentioning women or initiated by recent widows, the collection includes some wills of women. Inquiries regarding material possessions and the rituals – both religious and civil – surrounding death and inheritance can be supported from these records and the property exchanges which followed in the wake of a testator’s death.

Historical Background

The later Middle Ages saw a flurry of religious guilds or confraternities established across Europe, reflecting not only a popular form of demonstrating piety among laymen and women, but also providing a means of creating and strengthening social bonds. Ireland was no exception to this trend, and the fifteenth century witnessed the establishment of a number of religious guilds, where members contributed to the support and upkeep of chantry priests who would pray for their souls in perpetuity.

Foremost amongst medieval Dublin’s guilds was the Guild of St Anne. St Audoen’s Church and St Anne’s Guild were extremely influential in the lives of the inhabitants of the western part of the city. The founding charter granted the Guild the ability to acquire and control property yielding up to 100 marks per annum beyond expenses.

Between its founding and its eventual dissolution in the late eighteenth century, the Guild of St Anne amassed a large portfolio of properties located largely between Winetavern Street and the western city walls, and from the quays to the southern city wall. The Guild also controlled individual properties in Dublin’s suburbs, with their reach extending to Dolphin’s Barn, Oxmantown, and Kilmainham.

After receiving properties, the Guild began leasing them out. The Guild’s lessees were frequently Guild members themselves, and they speculated on rental rates, attempting to lock in low rates on decades-long leases created years in advance of possession and exchanged as commodities. When the Guild acquired a property, they also received previous deeds, which were kept in case of any subsequent claim to the property.

The surviving deeds span nearly five hundred years and preserve chains of property ownership that reveal, often in granular detail, the building patterns, industries, and lives of the Dubliners who lived and worked in the western half of medieval Dublin: merchants, aldermen, scriveners, and especially bakers.

They contain evidence of property ownership, including chains of owners and renters, and economic development, with buildings being built, rebuilt and destroyed, as well as the beginnings and growing influence of the Guild of St Anne. There is material of interest here not only for historians, but also for archaeologists, palaeographers, and sigillographers.

The deeds reveal how Dublin’s mercantile class lived, worked, and interacted, from those in high civic and church offices, to merchants and craftsmen, to widows, underage heirs, an apprentice, a mistress, a scheming bishop, and a horse named ‘Hackney’.

Archival History

Prior to the destruction of the Four Courts in 1922, the Public Record Office of Ireland (PROI) held thousands of individual, original deeds recording legal transactions between two or more parties. These individual deeds comprised both original documents bearing attached seals vouching for their authenticity, and later copies with no seal attached.

The PROI also preserved transcriptions of original deeds in the form of copies transcribed into cartularies or enrolled in rolls. In many cases, the text of an original deed would have survived only in the form of such transcripts, or as copies of deeds which entered the government’s records as the result of legal proceedings which arose from issues of land disputes transacted in the courts.

In addition to copies of deeds which formed part of the state’s official records, many hundreds of deeds contained in the Four Courts also had their origins in private collections, which were lodged for safekeeping in the PROI. These included, for instance, the records of parishes of St Catherine or St James (both located inside the walls of medieval Dublin), as well as several thousand deeds from the records of Christ Church Cathedral dating from 1174–1684 (https://virtualtreasury.ie/curated-collections/christ-church-deeds).

Although the original deeds of St Anne’s Guild were not lodged in the PROI, they represent an invaluable set of indirect replacements for the deeds lost in 1922.

The Guild of St Anne ceased to exist in the nineteenth century. Medieval and early modern manuscripts relating to the guild were acquired by historian and book collector Charles Haliday, MRIA (1789–1866). After his death, the Guild of St Anne manuscripts were among the extensive collection donated to the RIA library in January 1867 by his widow, Mrs Mary Haliday. The Charles Haliday collection of manuscripts in the RIA includes medieval documents relating to the Guild of St Anne.

The deeds have been catalogued at least four times since the dissolution of the Guild in the late 18th century: first in 1772 by James Goddard, then clerk of the guild, next by Henry F. Berry in 1904/1905. Later they were ordered by regnal date and numbered by archivists and librarians at the RIA.

Finally, in 1951, Ludwig Bieler created a typewritten catalogue, now fully digitised and accessible through this Gold Seam.

The Calendar

Ludwig Bieler (1906 – 1981)

Discover more about Ludwig Bieler in the Knowledge Graph for Irish History.

In the 1950s, the Irish Manuscripts Commission (IMC) engaged Ludwig Bieler to catalogue the deeds of the Guild of St Anne. Bieler summarised each extant deed, rendering the contents of many Latin deeds into English. For each deed, Bieler created a substantive English entry recording the type of document it is, the names of the individuals involved and any witnesses, descriptions of properties, where present, and notes regarding notes on the dorso, seals, damage, or other things that might identify each deed.

Where text was faded or missing, he used Goddard’s 1772 Abstract Book, which records the contents of deeds that no longer existed when Bieler made his catalogue, and occasionally Berry’s summaries, to supply additional information. Bieler’s summaries of deeds are extensive and many are analogous to translations of the original Latin documents. Bieler also recorded the presence of seals, identifying more important examples, such as the Seal of the Provostship of Dublin, and he included transcriptions of notes written in the early modern era on the backs of the parchment deeds.

Editorial Conventions

In his English summaries, Bieler removed most of the formal legal turns of phrase, but retained important details. In most cases, Bieler’s calendar is highly accurate in recording the particulars of the deeds, minus the legal phrasing that would make his entries more akin to true translations.

The language used in medieval deeds was highly formulaic. In general, standard elements such as opening and closing clauses, dating clauses, and standard legal formulae have been omitted.

The deeds in this collection often contain recitals of previous charters, or repetitive details, in order to specify the property or precise terms of the transaction. The digital calendar omits such repetitions, unless new information is included, but indicates instead the calendar entry in which the fuller version may be found. The language and technical terms used by Bieler have largely been retained.

Editorial interventions are indicated in square brackets. Occasionally, obscure or unusual terms or phrases in Latin, French or Middle English are included in round brackets. Gaps in the text are indicated by ellipses within square brackets: ‘[…]’.

In general, dorse notes have been left as they were rendered in Bieler’s typescript.

Bieler normalised the spelling of given names (e.g. ‘Iacobus’ in a Latin deed has been rendered ‘James’ in Bieler’s catalog). We have retained these spellings.

Surnames vary considerably, and Bieler largely adhered to the spelling on each deed.

Where inaccuracies occurred in Bieler’s descriptions, we have made silent interventions to correct these, using the deeds themselves as well as cross-checking names on other deeds to ensure accuracy.

Understanding The Records

Deeds

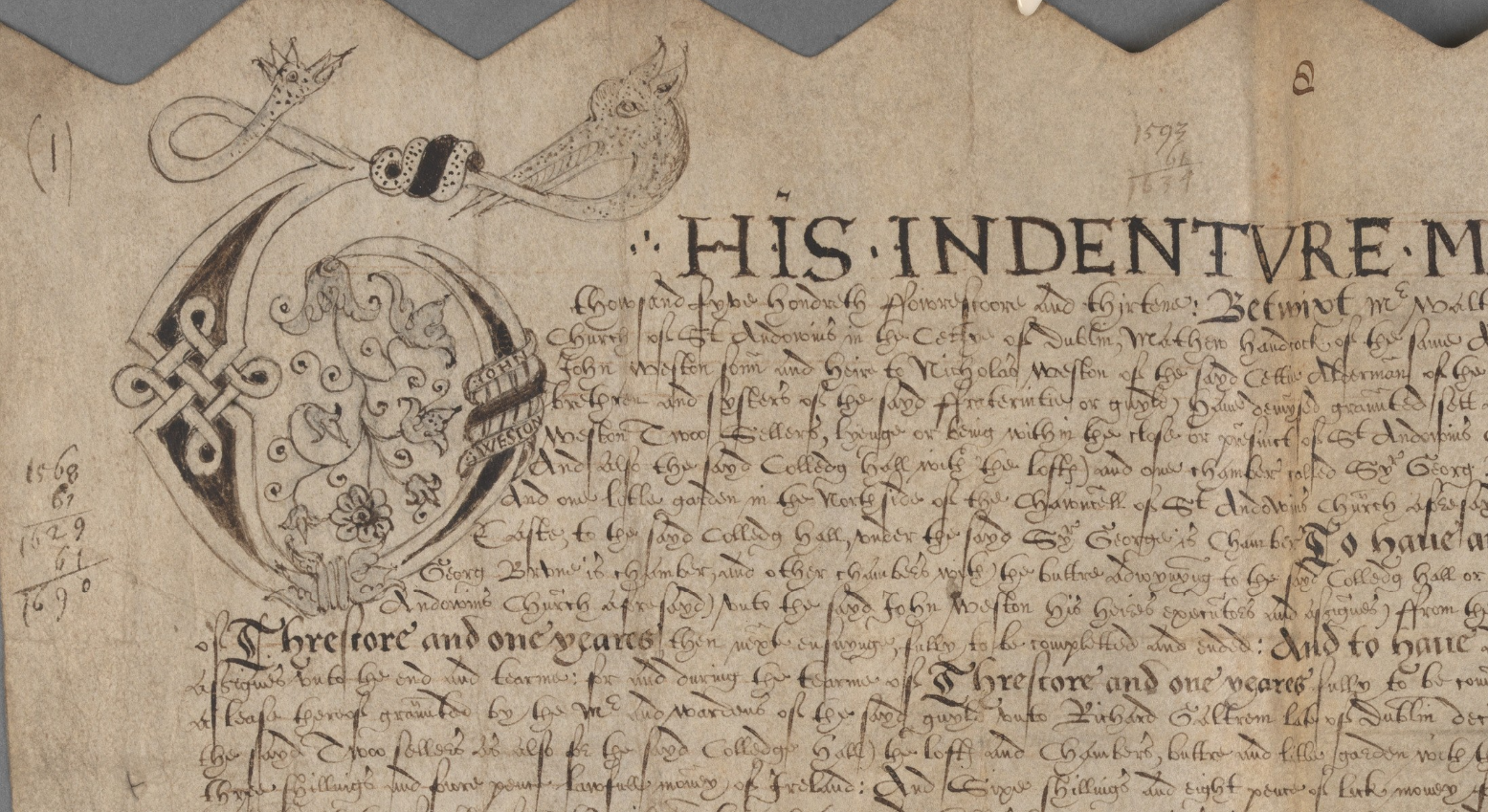

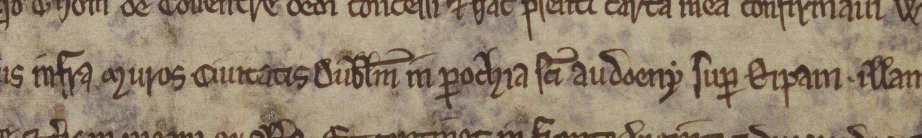

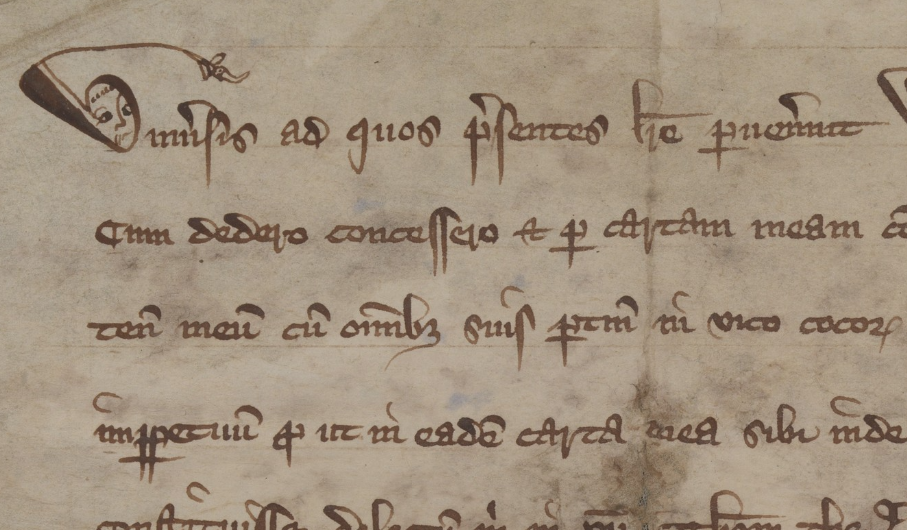

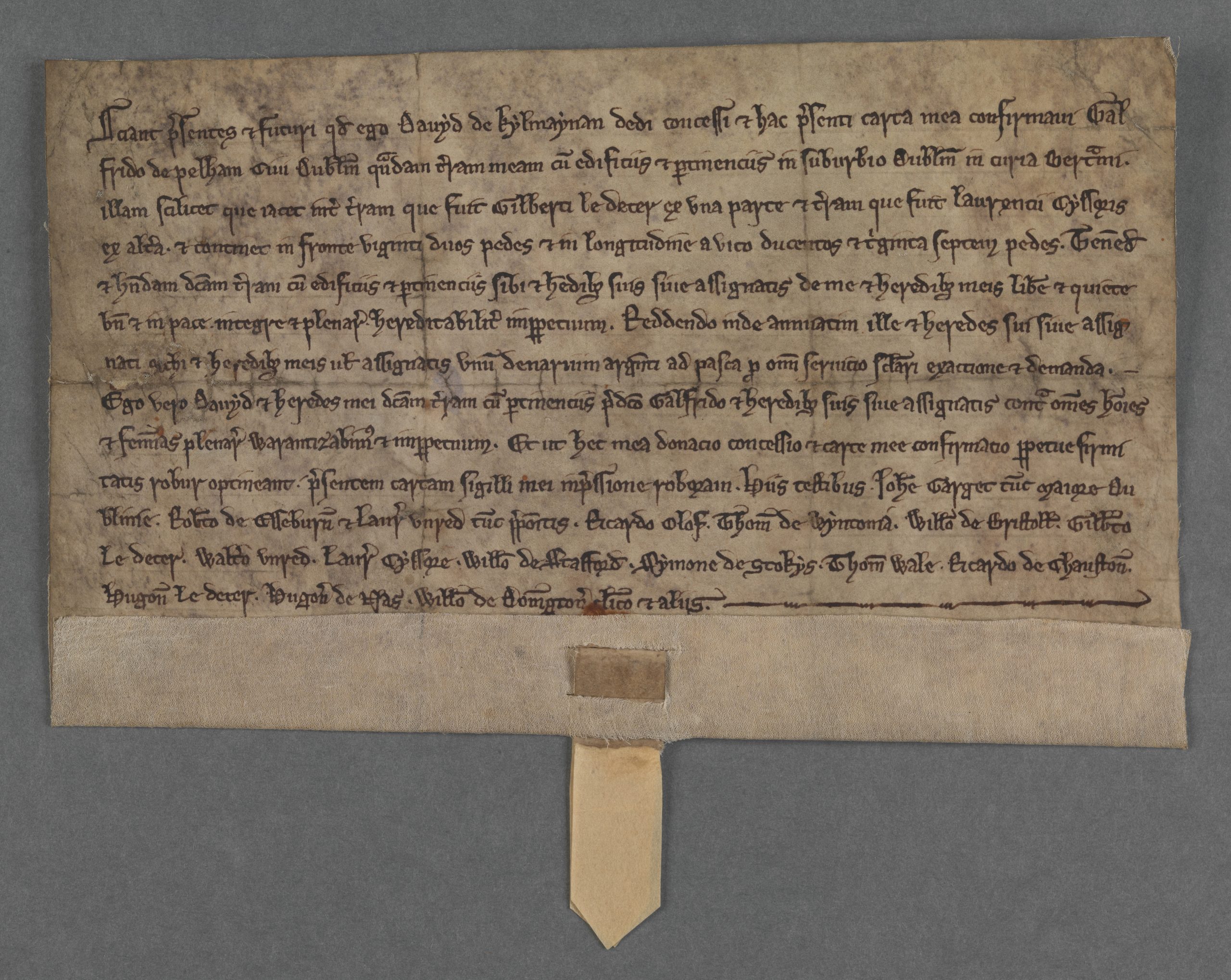

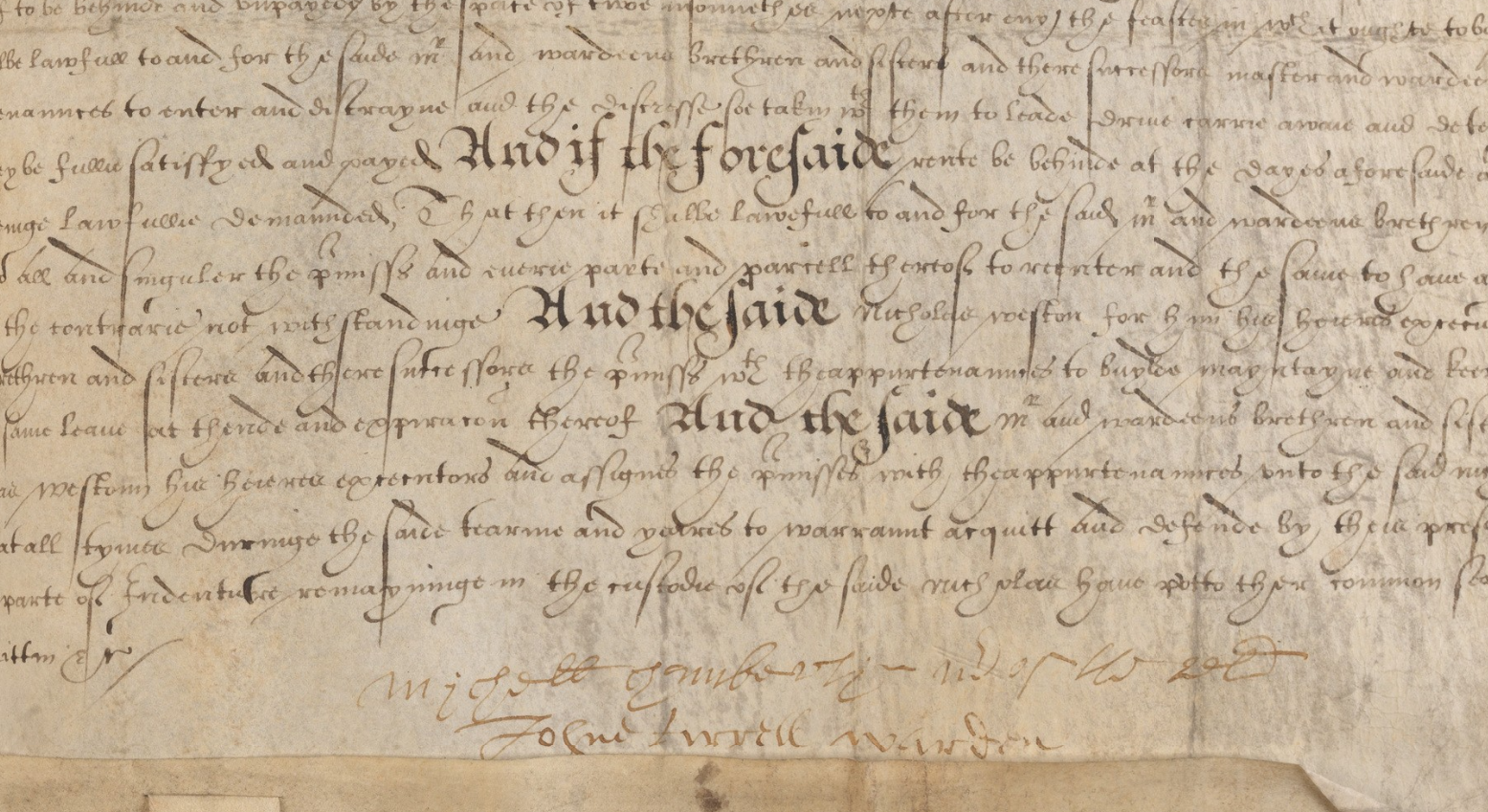

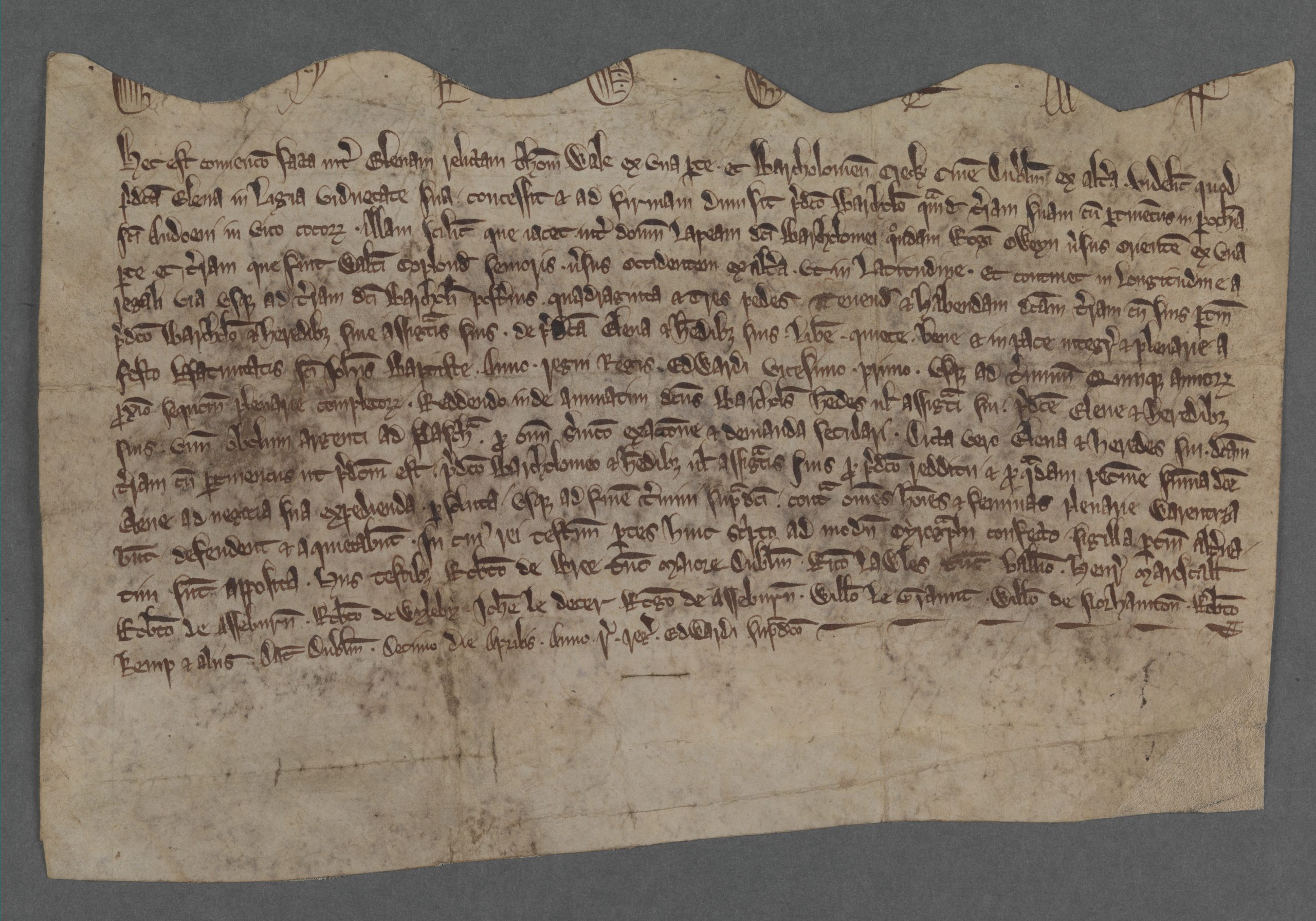

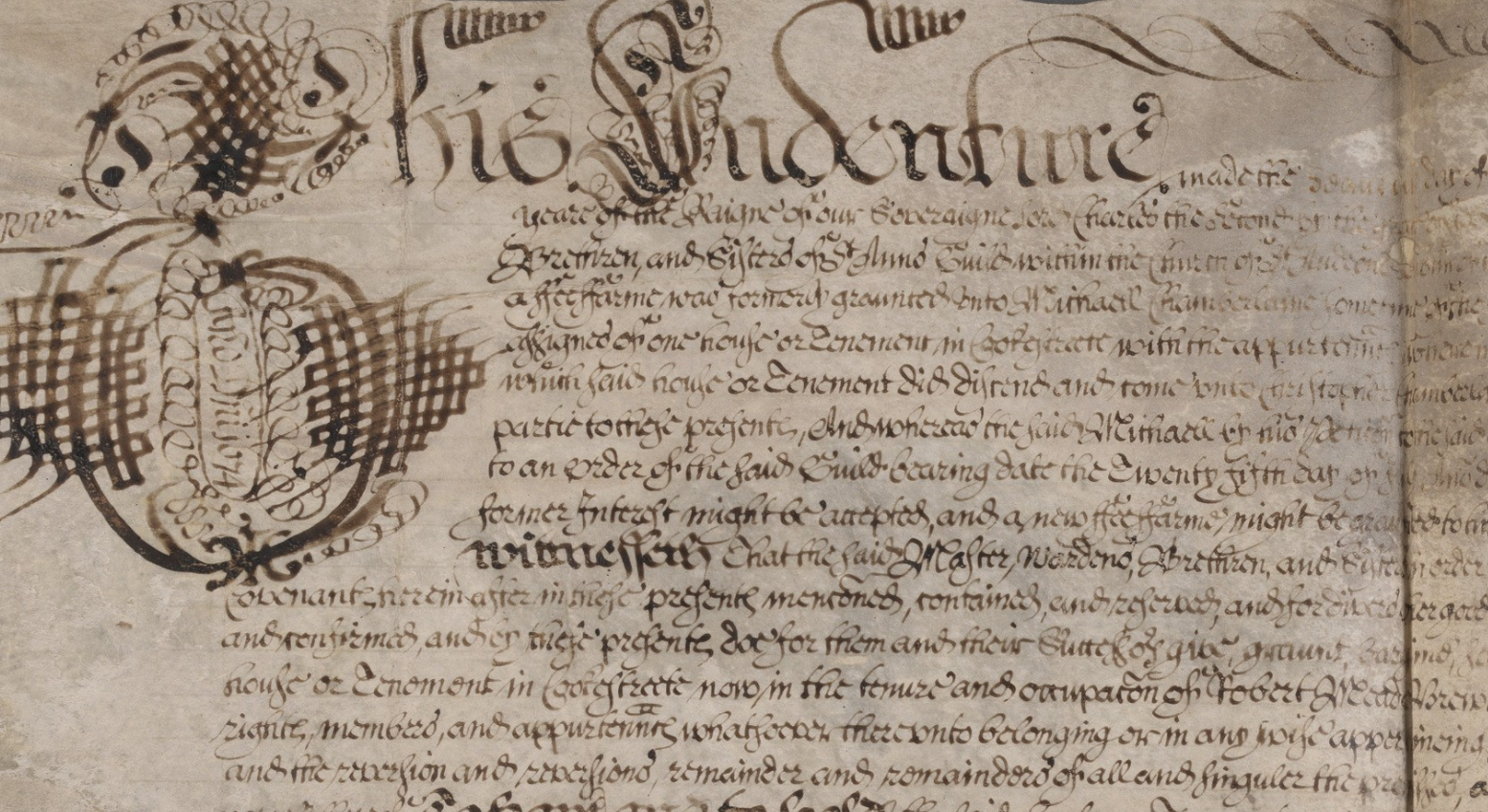

Medieval deeds are handwritten documents, usually recorded on a single membrane of parchment or vellum — animal skins specially prepared for writing. Most are written in Latin (or occasionally in French), but from the later fifteenth century English is increasingly common.

Deeds, or charters, were public letters people used to convey property to one another. Although deeds mostly concerned transactions from one party (the issuer) to another (the beneficiary), they are typically addressed to a public audience. Accordingly, the deeds in this collection typically open with the phrase to ‘those whom the present writing shall reach’ or to ‘all who shall hear and see this charter’.

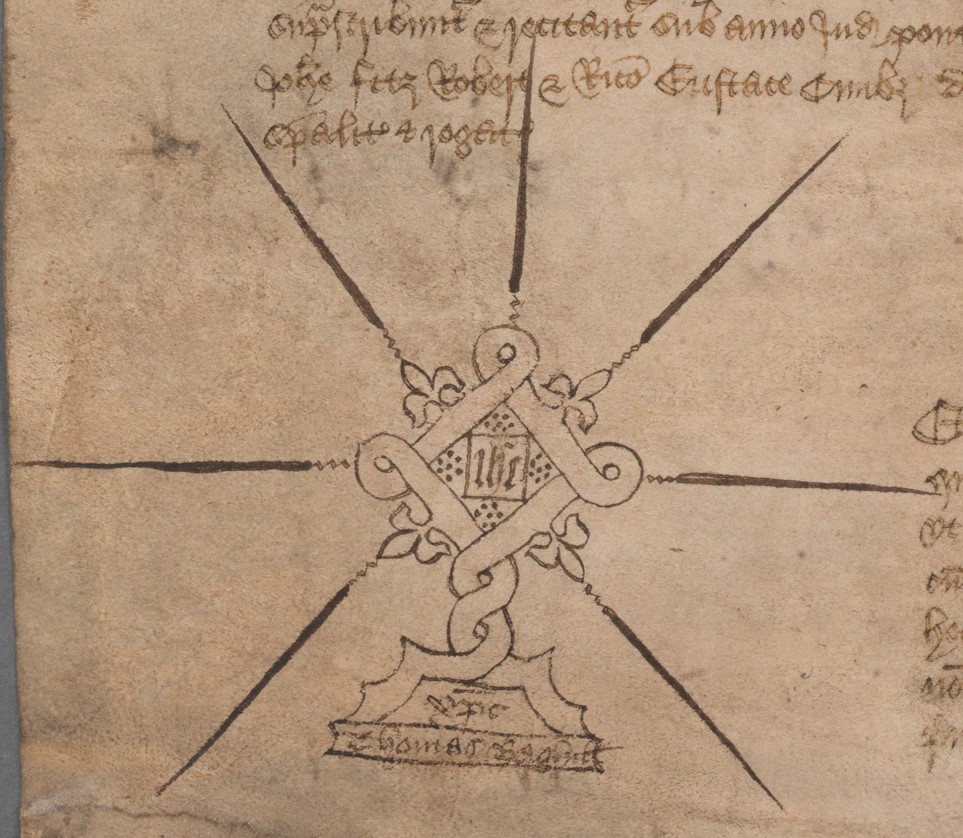

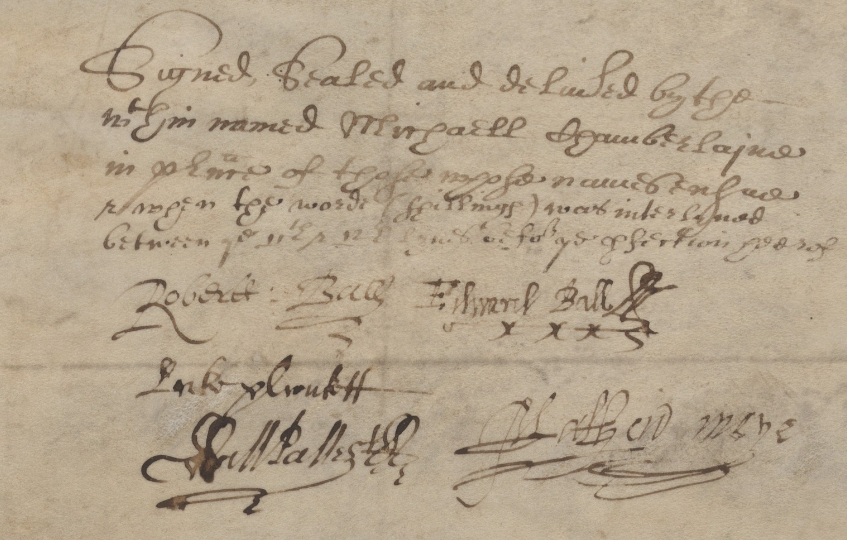

By the mid-thirteenth century, use of charters was no longer the preserve of the royal court, or members of the nobility and ecclesiastics; those further down the social hierarchy were also using charters to convey property to each other. Although literacy amongst the laity was by no means universal, and writing (and reading aloud) of charters and other records was generally done by clerks, medieval people could participate in the creation of deeds in other ways. Seals and signa, for instance, allowed a person to put their name to a document. Many deeds had seals, often made of red wax, which could be attached to the deed, hanging down from a reinforced plica, or alternatively imprinted directly onto parchment or paper document itself.

Rights over land were the most common form of conveyance contained in medieval deeds, but they might be used to convey any form of property; indeed, charters were also used to convey other gifts, such as items of clothing, silverware, or livestock. The usual formula used in a deed for a grant of land from one party to another was: ‘I have given and granted, released and quitclaimed.’

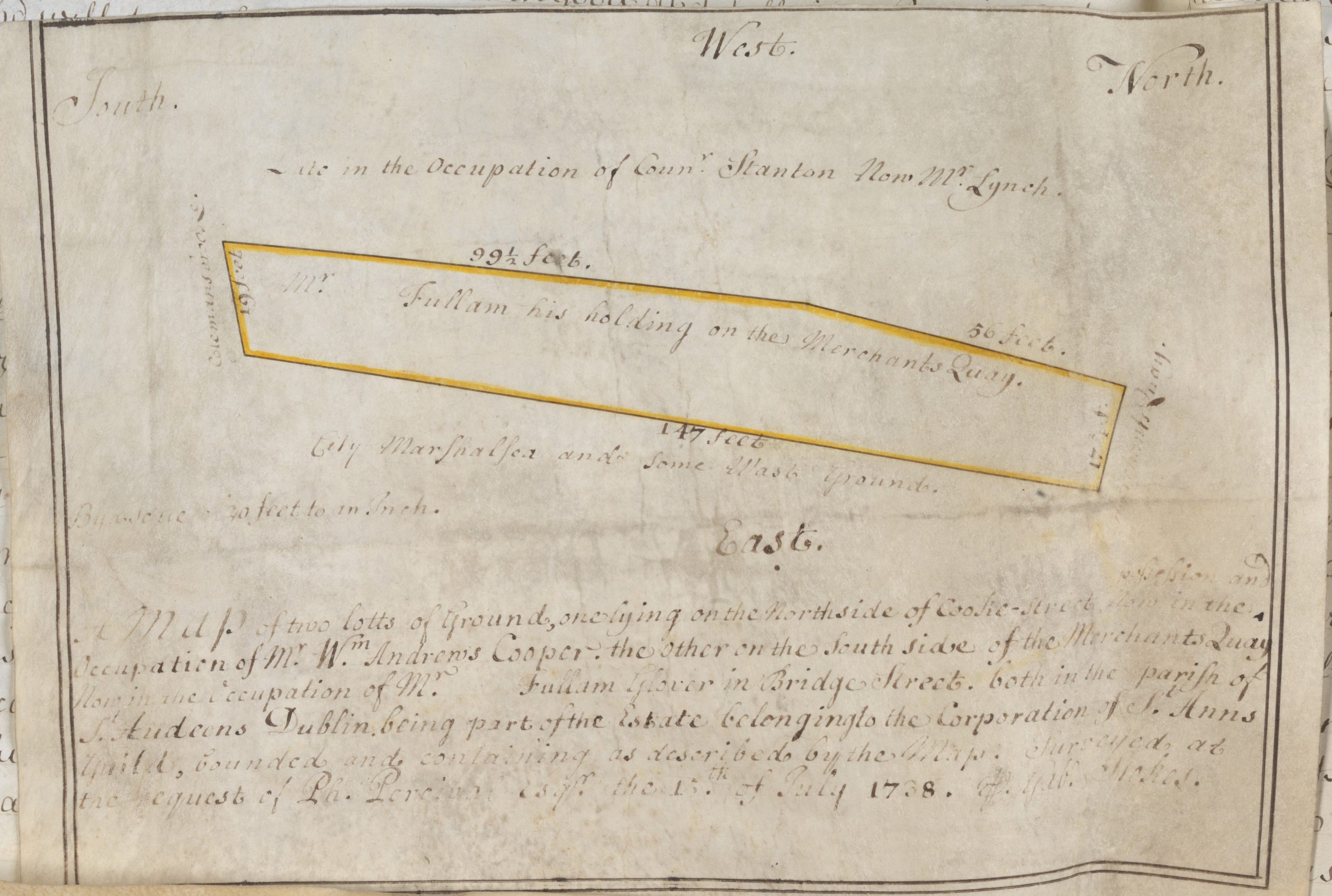

Conveyances were often described in great detail, and descriptions of properties or parcels of land could vary considerably depending on the nature of the property, and the date upon which the deed was made. In deeds relating to urban properties or plots, measurements were usually given in feet, and often appear in conjunction with a cardinal direction. Larger land measures were usually given in acres and carucates (a medieval measure indicating a unit of land which could in theory be ploughed in a single year by eight oxen).

A deed concerning the initial transaction of a specific property might only contain vague details, discernible only to those with local knowledge; the same property in a later deed might be described in great detail, with reference to specific landmarks, adjoining properties, previous owners, and even current neighbours.

Anatomy of a Deed

Most deeds follow a basic structure and form, containing the following elements

- the purpose of the deed

- the names of the individuals or organisations involved

- a summary of the activity which has led up to the present deed (e.g. details of a previous conveyance)

- a description of the property which is subject of the deed

- the terms of the estate

- details of agreements which affect the property and transaction

- a list (and often seals or signia) of witnesses to the transaction, typically including the parties as well as independent witnesses

- the date of the deed, typically represented as a regnal date, indicating the year of the reign of a particular monarch. Days and month may sometimes be indicated by reference to a particular event or saint’s day

- endorsements, or things written on the reverse of a deed

Indentures

Indentures, or chirographs, are different in format from charters, but were often used for much the same purpose. An indenture also records an agreement between two parties. The agreement might relate to a conveyance of land, but could also extend to other matters, such as a marriage settlement, or repayment of a loan. Whereas charters typically involve one document, issued and sealed by the grantor and given to the beneficiary, an indenture indicates a slightly more involved process, designed so that each of the parties received a copy of the agreement to which they were party. This meant that, in the event of a dispute, the copies of both issuer or beneficiary could be checked against one another.

The process of creating an indenture was straightforward: the agreement was written out in duplicate, on the same sheet of parchment or paper. Between both copies, the word CHIROGRAPHUM or another formula was written; the parchment was then cut in two, bisecting the two agreements along the line of the CHIROGRAPHUM or phrase. This process was designed to prevent forgery; the authenticity of one document could be checked by aligning it with its counterpart. Such deeds were often cut in a wavy or jagged line – literally ‘indented’ into the parchment itself, giving the name to this type of record. Indentures were popular instruments for recording agreements in the Middle Ages; some were even made in triplicate, so that a third copy might be kept in an archive for safekeeping or reference.

Property owners, such as the Guild itself or its members, preserved deeds in order to ensure that their title was secure. Within such archives, deeds were frequently stored in bundles with documents ranging in date from decades to centuries. Each time a property was conveyed from one party to another, the deeds were handed over from grantor to grantee; and so each time a property changed hands, new records were added to the bundle of deeds.

Other deeds

Other types of documents occur in collections of medieval deeds. These might include testimonials, wills, memoranda, and other records, some of which bear similarities to charters or indentures but do not necessarily concern property transactions. For instance, many deeds take the form of recognizances, which concern the payment of debts.

Glossary

Fine: a sum of money paid after a set period of time, such as the end of a lease, or upon the death of the holder of land.

Landgabulum: much like ground rent, this was an annual land tax, payable to the king or local lord.

Messuage: the area of land used by a house and its associated buildings and land; typically a dwelling-house and perhaps a garden and outbuildings.

Quitclaim: a waiver of rights designed to secure transactions, also used as instruments to convey land. Parties who might bring a claim against a new owner to return the property to them might be required to sign a quitclaim.

Index

This provides a list of surnames with spelling variations to assist with finding names of individuals across several deeds. Click here to access the index.

Further Reading

H. F. Berry, ‘History of the religious guild of S. Anne, in S. Audoen’s church, Dublin, 1430–1740, taken from its records in the Haliday Collection, RIA’, PRIA 25C (1904–5), 21–106.

M. T. Clanchy, From memory to written record, England 1066–1307 (3rd edn, Oxford, 2013).

Directory of Historic Dublin guilds, ed. Mary Clark & Raymond Refaussé (Dublin, 1993).

Philomena Connolly, Medieval Record Sources (Dublin, 2002).

Colm Lennon, ‘A Charmed Life: Prayers, Property, and Perseverance in St Anne’s Guild’, Deeds of the Guild of St Anne, 1237-1779 — Hidden Stories (VRTI, 2025).

Colm Lennon, ‘The chantries in the Irish Reformation: the case of St Anne’s Guild, Dublin, 1550–1630’, in Religion, conflict and coexistence in Ireland: essays presented to Monsignor Patrick Corish, ed. R.V. Comerford, Mary Cullen, J.R. Hill and Colm Lennon (Dublin, 1990), 6–5, 293–297.

Theresa O’Byrne, ‘Bilingual, Bitextual Bellewe: A Case Study of Paleographical Code-Switching in Late Medieval English-Controlled Ireland’, Speculum, 99:3 (2024) 744-761.