Parchment Conquest, 1171–1307

Delving Deeper

This page provides descriptions of the documents in the Gold Seam, together with historical background and archival context. The information here is aimed at researchers who want to delve deeper into these fascinating collections.

Cite This Essay: John Marshall, Paul Dryburgh ‘Calendar of Documents Relating to Ireland, 1171–1307 — Delving Deeper’ (VRTI, 2025).

Introduction

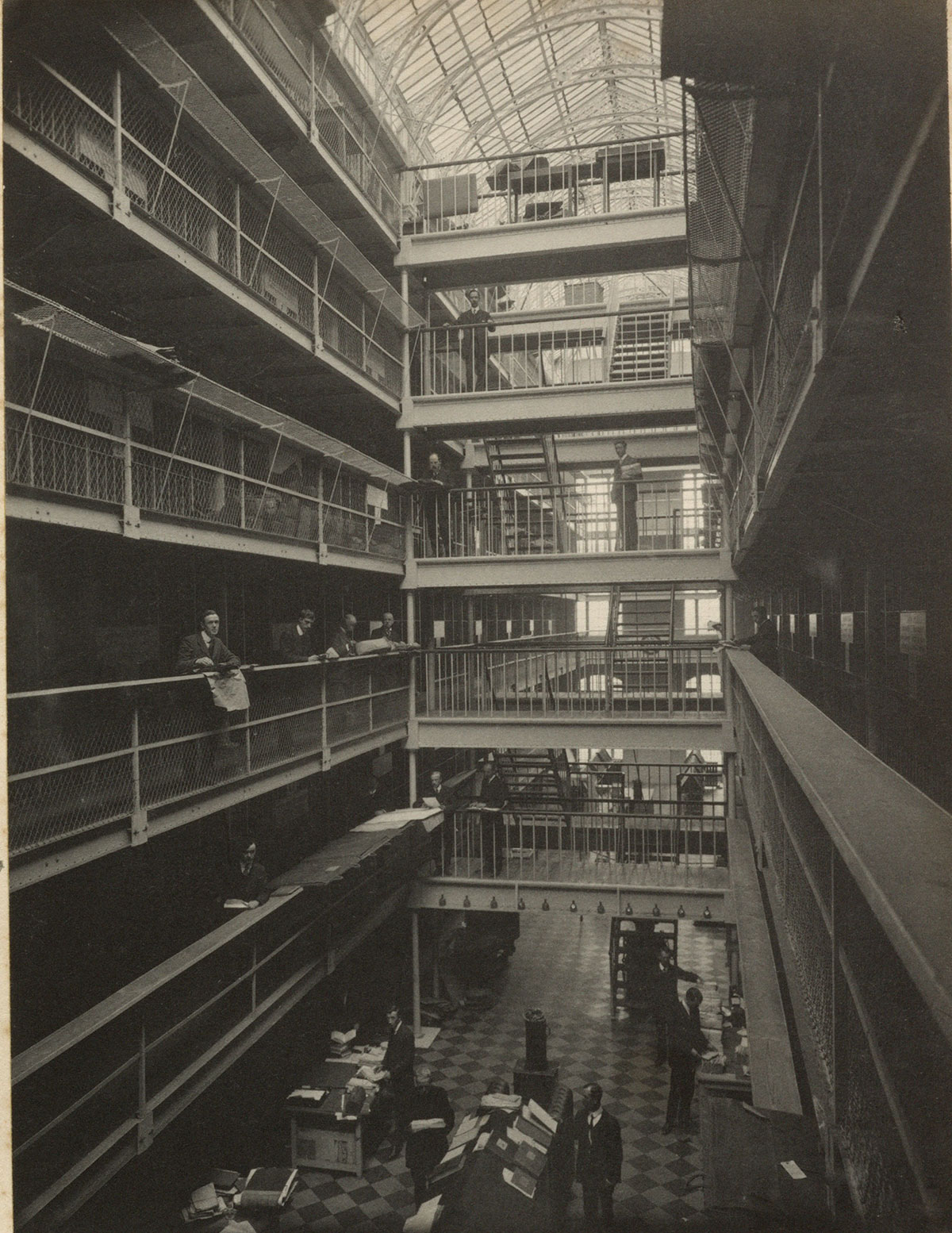

The destruction of the Public Record Office in Ireland in June 1922 destroyed much of the rich records produced by the English government in Ireland. Yet much of the inner workings of Ireland and the vibrancy of society can still be gleaned through material produced by the government in England.

For the medieval period, we have surviving letters sent by the king and his officials to Ireland, as well as royal charters granting lands and financial records relating to the exchequer in Ireland. At the same time, TNA also preserves documents sent from Ireland, such as letters sent by Irish kings or religious institutions throughout the country, Ireland’s importance meaning that the documents relating to the country also involve the papacy and the Holy Roman Empire as well as international trade and commerce.

Historical Background

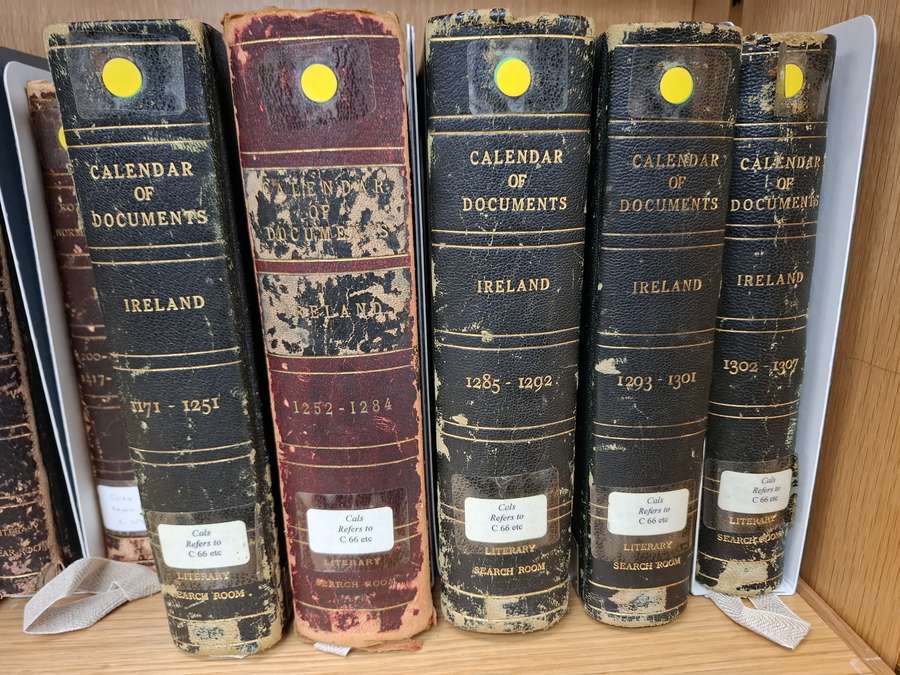

The Calendar of Documents Relating to Ireland (CDI) comprises short calendared entries of the known records relating to medieval Ireland in the Public Record Office (now The National Archives, UK). Compiled in the late nineteenth century by the Dublin-born barrister Henry Savage Sweetman, the five volumes calendar 8,351 documents relating to the period 1171–1307, and hence provide a rich perspective on Ireland’s medieval past.

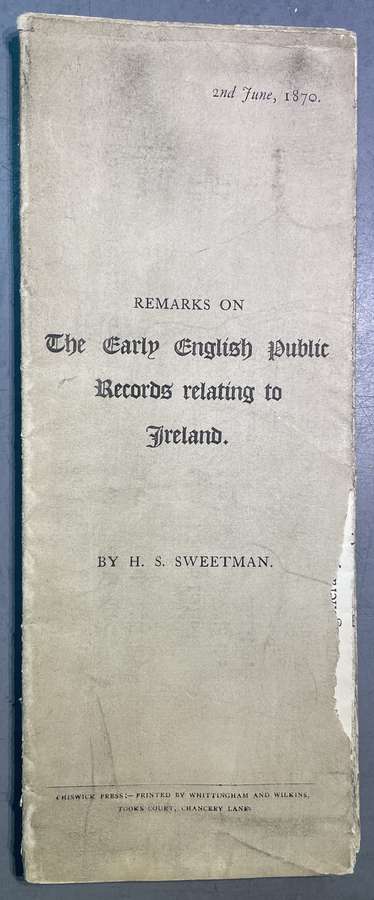

From correspondence concerning Sweetman, we know that he first broached the project in 1864, though the then Deputy Keeper, Thomas Duffus Hardy, showed little enthusiasm. Over the years which followed we find Sweetman working to show the value of the calendar and why he was the one to complete it. In 1868, Henry compiled a collection of extracts of deeds and writings found on the King’s Remembrancer memoranda rolls for the reign of Edward I (1272–1307), demonstrating that he could engage with documents. In the same year, on 14 December, he gave a lecture to the Royal Irish Academy on records relating to Ireland housed in England, which he published two years later as a pamphlet (TNA, LRRO 11/5).

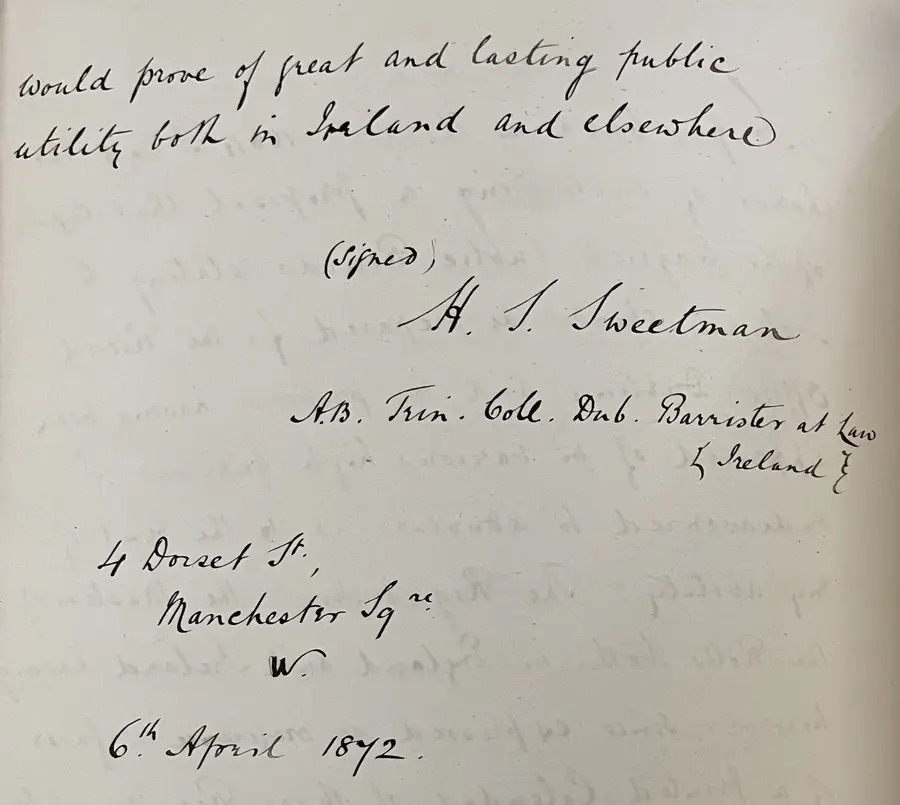

In 1872, Sweetman again wrote to the Deputy Keeper expressing his enthusiasm for the project, which he envisioned would calendar documents relating to Ireland from the reign of Henry II (1154–1189) up until the reign of Queen Victoria (1837–1901), this later being trimmed back to conclude with the reign of Henry VII (1485–1509), thus complimenting an ongoing project to calendar the Tudor State Papers, led by Hardy and John Sherren Brewer. Henry was officially commissioned late in 1872, being paid £200 annually from 1 April 1873 and at £5 per sheet, each volume containing 40 sheets (or 640 pages).

And so CDI was born. Sweetman only lived long enough to see four volumes published, the fifth being seen to press by G.F. Hadcock. Nonetheless, CDI remains a monumental achievement, made all the more important by the destruction of the Public Record Office in Ireland fifty years after Sweetman began his efforts.

Henry Savage Sweetman and his calendar

Born on 11 March 1810, Henry Savage Sweetman was baptised the following day as a Roman Catholic in St Mary’s Pro-Cathedral, Dublin. His parents, William and Jane, were affluent brewers and bakers who owned Raheny House in County Dublin. In 1829 Henry entered Trinity College, partly due to the passing of the Roman Catholic Relief Act that same year. This act removed many civil restrictions on Roman Catholic citizens, including the right to enter higher education. At Trinity College, Henry obtained a bachelor’s degree and later studied to become a barrister, and in 1837 he was admitted to the bar at the King’s Inns, Dublin.

By 1841 Henry had left Ireland, though it is not known why. The England and Wales census records him lodging on Manchester Square in Marylebone, London. This census describes him as ‘aged thirty’ and of ‘independent means’. Henry was clearly fond of Marylebone as, in the 1851 census, he was recorded as lodging there again, though he had relocated to 11 Bentinck Street, a five-minute walk away from his previous boarding house. This census records that Henry, now forty-one, was a ‘barrister not practicing’, so it is likely he had a sizeable private income, probably from lands the family held in counties Dublin and Armagh.

By the time Henry’s pamphlet on the English records relating to medieval Ireland came out in 1870, he was living at 4 Dorset Street, Manchester Square. At the time of the first volume’s publication in 1875, Henry was living at 8 Abbey Gardens, Abbey Road, London, five doors down from where Abbey Road Studios of Beatles fame were later located. Sweetman then subsequently moved to 38 Alexandra Road, about a ten-minute walk away, where he lived from 1877 until 1881 as a boarder with the historical author Sutherland Menzies.

Little is known of Henry’s later activities until 9 February 1884. Here, we find a letter by his nephew, John Andrew Sweetman, which was sent to the Master of Rolls, William Baliol Brett, 1st Viscount Esher. According to his nephew, in September 1883 Henry had been knocked down by a black cab in London, causing concussion of the brain which resulted in ‘absolute and hopeless lunacy’.

John sought financial support for his uncle from the British government, for which he secured the support of the Deputy Keeper, William Hardy. It is not clear whether Henry returned to Ireland after the accident, though we know from his death certificate that he died in Brooke House Asylum, Hackney, on 5 August 1884 of ‘Cerebral Anaemia’, Sweetman then being buried in Hackney.

Sweetman’s life was a story of triumph and tragedy. From north county Dublin, he ultimately made London his home as he devoted his efforts to promoting and making accessible records integral to understanding Ireland’s medieval past.

Inspiring Generations

The painstaking efforts of Henry Savage Sweetman has galvanised countless historians in the time since, affirming the importance of English records for understanding medieval Ireland.

We know also that Sweetman’s work on Ireland stimulated a similar project calendaring documents relating to Scotland in the Public Record Office.In the preface to the first volume of his calendar, its editor Joseph Bain paid homage to Sweetman, ‘whose valuable Calendar has been the model on which the present one has been drawn up, he has been often indebted for counsel’.

Ultimately Sweetman’s legacy looms large over medieval Ireland. Each and every document calendared in CDI provides a rich perspective on the complex and vibrant society in the country following the English invasion. As this Gold Seam highlights, CDI should be the first port of call, not the last, and perhaps the most fitting contribution to Sweetman’s legacy is that those interested in medieval Ireland continue to engage with original manuscripts.